Rooth, Groff and Mr Smith: Dead Reckoning

“That twitching red mess in the ditch could have been me.” In this ride to the dark side, Two Wheels magazine’s three legendary columnists look death in the eye, and throw camshafts in his general direction…

Rooth: Spiderman

The lightning started on the outskirts of Moree at about the 13-Mile mark. lt might have been firing for longer, but one fuel stop and the sun had slipped down as quickly as a card being swiped.

It wasn’t above me. No, in that incredible expanse of western sky all I could see was stars in all directions. Except one. The one l was going in. Somewhere down there, probably 100 kilometres or more away, they were copping a hell of a storm. There’s something very special about nights like this. Mother Nature raging away, letting the world know who’s still boss. Mankind reduced to cowering sheep as the sky booms.

This is typical of the west, one of many reasons l’ve always been drawn to that place where flat paddocks disappear into their own perspectives.

Years ago in Lightning Ridge we used to watch black clouds – scuds, to use the local term — scoot across an otherwise blue summer’s sky. Where they chose to dump their load was as random as finding opal itself. lf they missed, you got home dusty. lf they hit, you’d be spitting mud and sliding sideways and hoping like hell they’d follow you home and fill all the tanks in the camp.

Yep, weird weather dominates the great western districts. Cold days interrupt stinking hot months. Mornings that see the world sparkling with dew before a dust storm blows the lot away. Years where even the fish dry up followed by thousands of acres of flood. People who think the west is boring have lost their grounding strap to Mother Nature.

Thirteen. Always an ominous number for me. Okay, so l’m superstitious. The little rituals l’ve developed over 30 years of riding have kept me alive — at least that’s my belief — so l always slow down for the number 13, wherever I see it. Maybe that’s why l noticed the lightning. Maybe not…

Yep, l’m still saying “God bless” every time a car load of nuns goes the other way. l’ve still got the same Saint Christopher medal stuck to the speedo of my bike that that Norton 30 years ago couldn’t rattle off. l swerve to the other side of the road for Volvos and never follow a truck hauling cars. I’ll park on the footpath, I’ll park where the signs say don’t, but I’ll never park in a wheelchair spot. l won’t run over a lizard, and l’d never swat a bug when l’m ready to ride. C’mon, a bloke doesn’t have to be a Buddhist to make sense out of karma.

None of that applies to drivers of little spastic trolleys who eat McOrribles and use phones when they should be driving. No, they deserve to be swatted. lt’s just the bugs a bloke should watch out for. They’re not the enemy.

The night was warm and the bike was running as sweetly as an old Harley can. l kept it down to 90km/h even though there hadn’t been a sniff of roadkill all day. You only have to hit one kangaroo in your life to know the difference between 80km/h and 110 is a wobble and weave or a trip in the meat wagon. Night-time riding is beautiful out west. Endless miles, countless stars, the absolute still when you switch the motor off for a pee. l love it.

My target was Dubbo that night and a warm bed before a run to Melbourne the next day. l was booked in already, just running a bit late thanks to a bit of ‘on-road’ maintenance. Actually l should have got there about the time the sun went down, but shit happens when you ride an old bike. Shit like a blown coil.

The lightning kept up, flashing through clouds in the distance and rolling off the side of the Warrumbungles to the east. But the air stayed warm even when the first few drops of rain blew off my visor. At the start of the hills before Gilgandra I thought “I’m going to miss this”… just as the heavens opened and sheets of solid water dumped down. The winds blew in from nowhere and suddenly the truck l was following, and l, were swimming for the side of the road in a sea of dead branches, leaves and solid rain.

ln the truck lights l saw the roadside table and its roof. Then l saw the truckie’s toilet and that’s where l sat out the storm. l was wet through and the swag was soaked, it was half an hour before midnight and a warm wind had kicked in from nowhere as if to signal the end of the rain. Bugger Dubbo. l camped the night on the concrete.

Next morning, some four or five kilometres past camp, l was slowed by some witches hats and men wearing vests. A cattle truck had hit a four-wheel drive during the midnight storm and there was oil all over the road. Three cars, one with a trailer, were scattered among the trees. That twitching red mess in the ditch could have been me.

With plenty to think about, l stopped at the truck stop before the river at Gilgandra for a big breakfast and a shower. As l opened my Dri-Rider, the one that’d been drying on the concrete all night, a black spider dropped out. lt stood next to my boot before scuttling across the floor. The lady at the counter gasped — she recognised a Trapdoor — and said: “Tread on it, tread on it!”

“No way,” l said, not moving an inch. “Not for all the tea in China. And can you make that a mug of chino, not a cup?”

No wonder they think we’re weird.

By John Rooth, Two Wheels, May 2005.

Groff: On Death

I’m just back from staring at myself in the mirror. The bathroom has one of those four-globe light clusters which burn the top of your head and highlight every line, crevasse, pockmark and scar on your face.

I smiled at myself weakly a couple of times to see what difference it made and I looked at myself side on, firstly in my comfortable posture and then with my stomach sucked in and at full stretch.

There’s no doubt about it: my body is changing. Over the past couple of years it feels like it has been in free-fall, exploring new territories of shape, size and function without anyone obvious being in control, least of all me.

It’s got some interesting scars, only some of which are from bike crashes. One of my favourites is a red welt which runs sideways across the ridge of my nose. It’s from glasses, but not the kind you wear to read. When I take the last mouthful of red, the top rim of the wine glass often smacks me on the nose. I drink so much these days the scar never gets a chance to heal.

Elsewhere, I have calluses on my right hand from the skin being compressed by screwdriver handles under pressure, scar tissue on my elbows, knees and hips from various high-speed slides and one ankle with restricted movement from frequently being sprained or broken.

I cut the top off the little finger of my left hand once on a bread-slicing machine. Initially, I didn’t realise what I’d done and couldn’t work out where all the blood on the fresh, white bread had come from. It was sewn back on but the nerves don’t work any more.

Inside me is gout, or, more technically, more uric acid than the average human body is meant to accommodate. It took years of searching, but I finally found a doctor who said it has nothing to do with drinking. Actually, I think that’s what he said — his accent is so thick it’s often hard to understand him. It’s a nuisance having to ride 200km for appointments, but everyone else would tell me to cut down on the vino intake. I understand their concern, but the choice should probably be mine.

When Wayne Rainey rendered himself paraplegic (in a crash at the 1993 Italian Grand Prix at Misano – Ed.) in what looked, on the surface, to be a minor spill, every motorcyclist in the world probably felt the chill breath of Fate caress the back of their necks. You can’t ride and not think sometimes of death or permanent disability. I swore a pact, once, with a Ducati 900SS rider named Maureen with whom I was close, that, if it was necessary, either one of us would switch off the other’s life support system. I’ve never forgotten but she’s a solicitor now and may feel differently when the time comes.

I’m not completely convinced about this, but I have a feeling that in some circumstances I might want the machines turned off. Whether it’s from old age, disease or a major stack, the future might be bleak enough to warrant some kind of direct action. Like gout and its treatment, the choice should probably be mine.

Back in 1983, in Alice Springs, I wasn’t thinking about any of this. I spent the long, hot days riding, playing music and cricket, drinking and writing. There is a surprising number of bikers in the Centre, but it’s hard for them. Wearing black when it’s 50°C looks cool but isn’t, if you get my drift. I had a view that I would live forever in perfect health, but I did have a brief conversation about mortality with a BMW owner.

There’s an American defence base just out of Alice which is a running sore for serious political activists. The BMW rider was prominent in the protest movement, but what he wanted to see me about was a ride he was planning over a particularly remote desert area. He wanted some advice on how to record it for possible publication in Two Wheels. I looked at his maps and the planned route, then I looked at his R60/6 (it might have been an R75/5 — my memory is going, too). We had a chat about the strong possibility that he wouldn’t make it and the likely consequences. He had medical assistance covered because, as it turned out, he was a doctor, but I still had serious reservations.

We talked briefly and indirectly about all motorcyclists confronting either death or serious injury but he ended up with a position which was difficult to argue against. Knowing the options, it was his right to choose.

I know he made the trip but no manuscript was ever produced. Perhaps I discouraged him by being so negative. If he was after fame, he achieved it anyway in different circumstances. His name was Phillip Nitschke, and he’s now leading a national debate on the right to choose.

For me, I’m still not sure. What becomes legal eventually becomes moral, but if I’m sure about anything it’s that no government should be able to decide on the life or death of its citizens, especially minority groups, without their explicit consent. Phillip’s argument is less complicated than this, but it may have consequences beyond the issues of mercy killing. Rainey accepted the consequences of racing and we all implicitly accept that any particular ride may not end up how we originally planned. If you ride a bike, you constantly have to argue your right to choose.

Hey, Phillip, have you still got your BM?

By Grant Roff, Two Wheels, March 1997.

Editor’s Note: Philip Nitschke is now the director of pro-choice voluntary euthanasia advocacy organisation Exit International.

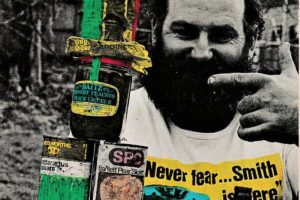

Mr Smith: Expecting the Unexpected

They always happen just when you least expect them.

Unexpected things, that is. I mean, it’s a bit like UFOs. Once you call them UFOs, they’re not Unidentified Flying Objects any more, are they? I bet you didn’t expect that line of argument. Anyhow, here’s the tale …

I was riding the Trusty Trailie along in the magnificent mulga at speeds bordering on the ridiculous … or about a quarter of what Jeff Leisk would get up to. The ground was stony, as was the ginger beer in my backpack. Plenty of concentration was required, but I didn’t have any.

Without much warning, forward progress ceased. This was somewhat unexpected, but not totally. The cause of same, I noted as I somersaulted deftly through the surrounding greenery, was a very professional stiff-arm tackle performed on me by a very large mature male of the species Megaleia rufa. And I can tell you, they don’t call ’em ‘Megas’ for nothing!

This was also unexpected, but not totally. I’ve seen shaved gorillas playing thugby league, but not yet ‘roos. It was only a matter of time, after all. When they can get the shorts to fit ’em, I guarantee they’ll be straight into first grade. Anyhow, the ‘roo hopped away muttering something about incentive payment schemes as I made contact bonce-first with Terra Verra Firma, accompanied by the appropriate soggy crunch, and did a very commendable impression of a dead Smith.

Looking up from my rather uncomfortable and increasingly sticky resting place, I noticed the figure of an extremely attractive woman walking toward me, bearing upon her shoulder an earthenware jar. She beckoned to me. Her lips didn’t move, but I distinctly heard the words.

“Come, drink.”

I sat up like I’d been bitten by a twelve stone bull-ant. “Bewdy,” I enthused. “After that rather frightening get-off, I’m tonguin’ for an ice cold!”

Without speaking she produced a fine silver goblet from the folds of her diaphanous costume. Into it she poured some of the contents of the jar, which sparkled like the stuff you find in your Xmas dinner after your maiden great-aunt has been a bit too friendly towards the sherry and chucked that multi-coloured sprinkly stuff all around the room.

She passed it to me. I drank deeply.

“Er, thanks a lot. Could I trouble you for a further taste? That cropper has knocked the wind out of the Smith sails and another drink’d fix me up nicely. Not a bad drop. Tastes like a blend of apricot nectar, Drayton’s Rich Port and embalming fluid. What is it?”

Again her lips didn’t move. “It is the Draught of Death, and I who bear it am Death.”

I looked at her again. “Not exactly what I expected, but I suppose that’d be right. A bloody sheila comes along, gets you half pissed and buggers up your day. Hurry up pouring another one. I’m drier than the Beirut Pommie Consul-General’s towel.”

Death did so and handed it over. “Funny,” she said. “It should have worked by now. Did you say your name was Smith?”

I drank the proffered drop.

“That’s Mr Smith to you, Ms Death. And I’ll have another one while you’re at it. I reckon I deserve it. After all, look what you’ve done to my bloody Bultaco, having that malicious marsupial knock me toes-up like that. And now my body’II be stuck out here where my friends — not that I have any — will never find it in a squintillion years, and when they do it’ll probably have been disturbed by animals … no doubt by a bunch of eastern European pig shooters from Melbourne. And I still have a whole bunch of one-liners I haven’t tried out on the lovely Colleen yet. Struth-arama! Pass me that jar!”

She did that, and at the same time began consulting a dog-eared notebook. “Here’s the problem. You’re supposed to die of a combined stroke and heart attack in front of your computer screen in a tin shed in inner Sydney in March 1994. That kangaroo incident was pure chance. It was not expected. Can I have my jar back, please?”

“No. Naff off. How can a bloke get on with existence when you gods and spirits and forces of nature are making such a mull of things. A bloody immortal bureaucracy! Go on, buzz orf! Jeez, that plonk makes a bloke feel a bit sleepy.”

I awoke as the sun was setting. I looked around. There was a broken ceramic carafe on the ground next to me, spilt blood-red wine all over the place and I had a blinder of a headache. The Bultaco was leaning up against a tree and started first kick when I finally managed to force myself to my feet and give it a try. There seemed to be no damage, which isn’t what I’d expected. I made it back to civilisation alright.

That was a couple of years ago. It’s now late on the last day of March 1994 and I’m sitting in front of a computer screen in a tin shed in inner Sydney, staring at the old Bultaco which is leaning up against the wall.

There’s a knock at the door. It had better not be what I’ve been expecting.

By Peter Smith, Two Wheels, May 1994