Road Test Notes

When it comes to the black art of roadtesting, Two Wheels has, thankfully, not adhered to its original editorial creed, as expressed in the first issue, back in 1968: ” … informative to most, interesting to all – and above everything else, offensive to none.”

Such a bizarre philosophy has to be understood in the context of the times. Bikes – big ones in particular – and riders, were copping heaps from the establishment in the late ’60s, for the usual stupid reasons. There was an ever-present threat that we would be legislated off the road.

One of the main aims of the fledgling Two Wheels was to protect motorcycling by portraying it as an enjoyable pursuit engaged in by abnormally normal people at a time when its image was anything but that, so the early issues presented innocent, enthusiastic fun, fun, fun, with lots of pictures of clean young things enjoying themselves on small capacity, socially acceptable bikes.

However, it didn’t take the magazine long to realise who its core readers were – bike freaks, who didn’t wear pressed trousers or short back and sides – and what they wanted – real tests of real bikes. The fact that we’re still here is largely due to Two Wheels’ willingness to tell it like it is. Suggesting what’s worth putting your hard earned on – and what’s not – has always been the mainstay of the magazine’s editorial coverage.

Over the years, the various editors of Two Wheels have copped plenty from disgruntled bike distributors whose latest model has met with a less than rapturous reception in these pages. “You’re only as good as your last road test” is a truism in this game, although some in the trade have a better understanding of the role of Two Wheels than others. They realise that advertising in a magazine with credibility is ultimately a far better investment than putting their bucks into a sales brochure.

In the magazine’s formative years, however, the world was a gentler place, and the tenor of Two Wheels road tests was more restrained than it is today. No punches were pulled in identifying specific problems, design faults and annoyances on test bikes – in fact the early road tests were some of the magazine’s toughest in this regard – but conclusions tended to be less black and white.

The magazine’s first road test? Would you believe the Lilac Electra, a 500cc BMW clone from Japan, on page 12 of issue Number Two.

Our first comparison test was in issue Number Three. The contestants were 250s: a Suzuki Hustler, a Harley-Davidson 250 Sprint H and a Honda CB250. After much equivocation, the Honda got the money. Issue Four had another 250 comparo, this time looking at three sporty Europeans: a Montesa Sport 250, a Bultaco Metralla and a Ducati Mk Ill. It was the perfect excuse for the boys to get out of the office for a thrash around Oran Park – a tradition which continues today – but they wimped out with an ‘It’s up to you’ verdict.

The first of Two Wheels’ regular monthly issues – September 1969 – brought Aussie motorcyclists the first ride impression of the Honda 750 Four.

Two Wheels’ man in Japan, Jack Yamaguchi, rode it, and cautioned, “One must keep his eyes on the rev counter, for his sense of noise and vibrations may not warn him of the danger zones,” while in one of motorcycle journalism’s more accurate prophecies, staffer Wayne Allen called the Honda “a machine which in its own way ushers in a new era for large displacement motorcycles.” How right can you be?

In the early ’70s, Derek Pickard was the magazine’s main road tester, and big stuff was his specialty. The cover of August 1972 shows Mr Pickard, resplendent in his Two Wheels leathers and a very fetching pair of brown suede boots, ready to do the business on a Benelli 650 Tornado, of which he said, “Its inadequacies make a disappointingly long list.”

Pickard gave the road tests a harder, more authoritative edge than before. His style was very matter of fact, but he didn’t hesitate to praise or criticise, and his brief was obviously to give the readers the facts and an informed opinion about how each bike stacked up against its competition.

He certainly got to test some knee-trembling machinery. In September 1972, he threw a leg over the Ducati roundcase 750GT (and took the owners manual down to his local Italian milkbar for a translation: there was no redline marked on the tacho and he wanted to find out where it was), plus a Norton 750 Interstate (“Once you’ve gripped the big black tank between your knees and rolled back the throttle the Interstate rider feels at home immediately”). In the next issue, the lucky bastard did the job on a Vincent Black Shadow and three MV Agustas!

Lester Morris was the magazine’s other main roadtester during this period. He rode hard and didn’t hesitate to call a spade a shovel either. Lester’s motorcycling career began shortly after WWII, so his knowledge, and opinions, were deeply rooted in tradition. Lester also tested “classic” bikes, usually British, and new machines, up until the late 1980s.

In 1974, Brian Cowan was the man in the saddle. Cowan was as much interested in how bikes worked as how they went, and with technical editor and off-road tester Mike McCarthy – who today enjoys a reputation as the country’s best judge of a car – forged a partnership that gave the magazine a level of motorcycle knowledge guaranteed to settle any pub argument.

Cowan later went on to edit Two Wheels in the early 1980s. His gift as a roadtester was being able to communicate complex technical information in a way that made sense to untechnical people. In his eyes, a bike lived or died according to how well the practice mirrored the theory.

He was as passionate about valve actuating mechanisms as he was about doing the ton. Who else could write, in July 1974, about a 650 Yamaha twin thus: “Dammit, all motors have periods of shaking interspersed with smoother sections, but somehow or other the 650 is a rejection of several important physical laws.”

He also pioneered the snappy road test intro: “What’s yellow, goes like the clappers and hurts between the shoulder blades? No kiddies, not a racing canary with arthritis; the answer’s the Ducati 750 Sport.” (October 1974.)

In January 1976 there appeared for the first time in the pages of Two Wheels the byline of Kel Wearne, the Hunter S. Thompson of the Hume Highway. Kel’s brand of gonzo road testing was based around ‘The Ride on the Open Road’, as he called it. The Ride was not just a road test, it was a trip, in all senses of the word.

He laid it on the line in the first paragraph of the first road test he wrote: “The best way to test large-capacity machines is to take them on long interstate blasts – it’s the only way to really understand and sort out their all round capabilities and market potential.”

But Wearne didn’t just ride a bike a long way, then write about it. He took you with him. His anarchic, anti-authoritarian approach to life meant a bike couldn’t be treated as a simple piece of machinery. A mutha’s purpose was to deliver a hit, so The Ride and The Bike were inseparable halves of a complete experience, and his genius was that when you read his stuff you were there.

Wearne ploughed furrows day and night up the Hume, Olympic and Newell Highways between Sydney (‘Diesel City’) and Melbourne at a time when you could name your speed and it was still a contest.

“But I’m travelling. Punching through those trailing white clouds overtaking Macks, Volvos, Whites, Inters and such, hoping that the sheer lack of time (it takes around 1.1 seconds to overtake a semi travelling at NHS – Normal Hume Speed – of around 110 km/h while you’re on 160 km/h) would ensure there wasn’t another Mack, Volvo, White, Inter or such about to emerge from the white spray and destroy the five and a half grands worth of Bee Emm (R100RS). Not to mention a good story. Apart from that, the ride up was relatively uneventful.”

His tests were full of anecdotes about other riders he met on his journeys and the country he rode across, and all the while his main concern was what this bike would do for your head, man.

The most memorable image from a Wearne road test has to be the shot of him astride the Honda CBX1000 Six at 160 km/h. Nothing unusual in that, except for the fact that he and the bike are airborne – flying a metre or so above the highway – having used a railway crossing as a launch pad (“The railway speed advisory signs were missed”).

In the April 1980 issue, testing the Harley FXS 80 Lowrider, Wearne divided large capacity motorcycles into two distinct groups: “Bikes where emotion is everything” (European machinery, and the Harley) and “Japanese smoothbores”, and complained that the emphasis on Oriental technology had caused Two Wheels road tests to become bland, car-style, number-crunching exercises, restrictive in their scope and lacking an appreciation of “the reason for why people want something.

“Magazine format tests have catered for, preached to and promoted the image of performance, statistics and the cafe kick. Perhaps half the buyers believe this is right, but there sure is a large group who are into bikes as impressions of art, something that looks different, handles different, and is strongly individual in a raw-boned, gut-tough kind of way.”

He had a point, and the magazine’s road testing style later recognised that different bikes require different treatment, but this was the era of the UJM (Universal Japanese Motorcycle) when the vast majority of new models came with an in-line four-cylinder engine.

It was also a time when more new bikes were being sold in Australia than ever before (or since), so readers wanted comparisons to be made between bikes which, in many cases, were very similar. The only way to do it properly was to get the facts, which involved measuring things, so the monumental two-page specifications were born.

As well as all the static specs, you got standing 400 metre times (averaged across three runs), 0-100 km/h times, braking from 100 to 0 and from 60 to 0 (both averaged across three stops), power and torque readouts on a dyno, acceleration times and shift points, plus a detailed summary which included an overall value for money rating.

The first half of the 1980s saw a barrage of new models from Japan, as Yamaha set out to knock Honda from the number one spot (nearly going broke in the process) and Suzuki and Kawasaki were caught in the fallout. Two Wheels was having a hard time keeping up. In the September 1984 issue, the magazine carried a record seven tests!

Roadtester Dave Bourne was a very busy boy, but he did a good job sorting out the forgettable bikes – of which there were plenty during this period of new model mania – from the good ones. Every road tester has prejudices – usually in favour of European machinery – but Bourne was probably the most objective tester the magazine has had. If it was fast and it handled, he liked it. If it wasn’t and didn’t, forget it. Col Miller, whose time at Two Wheels began earlier but overlapped with Dave’s, took a similar approach. Anthony Seymour was a fast, accurate, informed tester – and a highly sought after mechanic who also wrote the Bike Doctor column and many stories on how to tune and service popular models.

The badge on the tank counted for little with these guys; an appropriate way of looking at things then because the Japanese were starting to work out what it takes to build a serious sports bike. The evidence arrived in 1984/85 in the shape of the Kawasaki GPz900R, the Yamaha FZ750 and the Suzuki GSX-R750.

In 1985, we decided to leave the dirt bikes to the dirt bike experts such as the late Geoff Eldridge, who by then had started Australasian Dirt Bike magazine, and concentrate solely on road machinery, of which there was more than enough to fill the pages.

The Wearne influence became more apparent, with plenty of open-road comparison testing through the late ’80s, and less emphasis on numbers, mainly because the blokes who were testing bikes during this period weren’t tech heads but heart and soul merchants, for whom seat of the pants sensations were just as important as quarter-mile times.

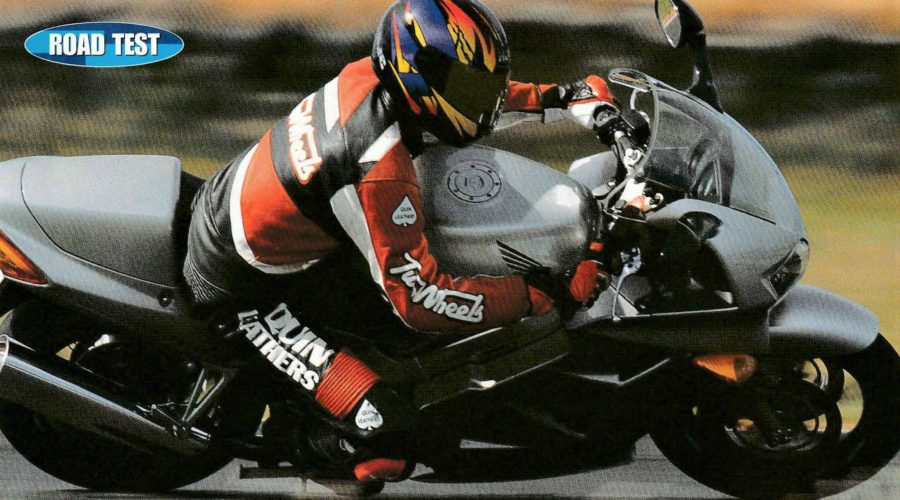

Testers like Mick Matheson (pictured on the Honda VFR800 at the top of this story), Geoff Seddon and John Rooth didn’t rely on calculators, but their getting it right rate when summing up a bike was no less than those who argue that the numbers never lie.

These three testers stood out for their ability to be able to communicate, with effortless, beautifully-crafted words, the sheer joy of riding a great motorcycle. And the disappointment of riding a mediocre one.

By the second half of the ’80s, Two Wheels had reached the stage where it was creating road test styles instead of the other way around. Several roadtesters had grown up with the magazine, so they wrote – subconsciously perhaps – in the style which they had enjoyed as a Two Wheels reader, and fortunately the new generation of Two Wheels readers liked it too.

The flow of new models – and sales – slowed right down, but the quality and variety of machinery was better than ever as the ’80s drew to a close, with the Europeans – particularly Ducati, which has to rank as the most favoured marque of Two Wheels roadtesters through the years – making a welcome comeback, specialist touring bikes developing as a genre rather than an oddity, Harley-Davidson dominating the big bike market and the Japanese producing fewer but far better motorcycles than before.

The result of this diversity in motorcycles, and the types of people who buy them, is reflected in the many different styles of road test you see in the magazine today. Road tests are now written according to the expectations of what the buyers of a model will be looking for, and recognise that information sharing is a useless concept when you’re talking Wide Glides and ZXR750s.

That’s the way things ought to be, of course. The ‘user friendly’ approach is the term the computer boffins give to it.

Knowing what readers want, and giving it to them (err … you) is probably the reason why the Two Wheels road test has always been the benchmark. This, and a steadfast refusal to take too seriously the simple act of riding a bike and telling others about it.

By Bill McKinnon. Two Wheels 25th Anniversary issue, November 1993.

Cover pic of Ducati’s Supermono by Phil Aynsley