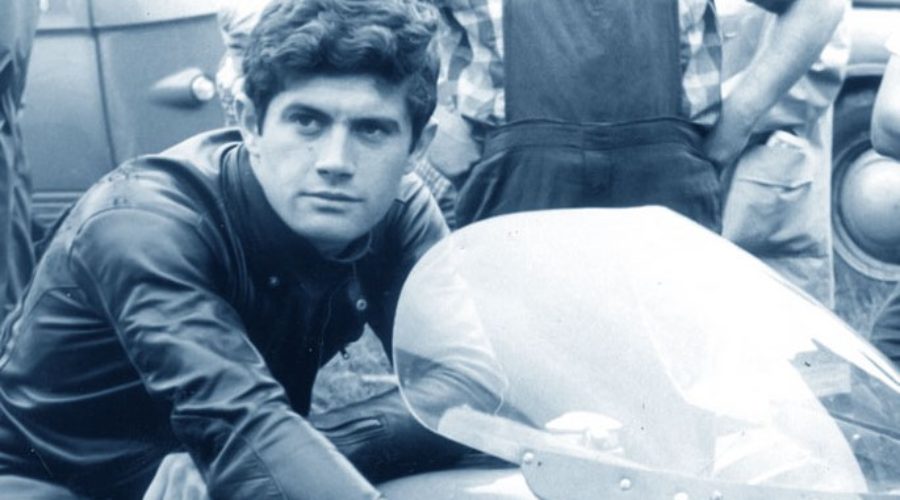

Racing’s Greats: Giacomo Agostini

Italy’s Giacomo Agostini holds the all-time record for the greatest number of world championships and grand prix victories.

Agostini between 1965 and 1976 won 122 grands prix in the 350 and 500 cm3 classes, and 15 world titles – eight 500 and seven 350. He won seven 500 titles in a row from 1966 to 1972, and another in 1975, and all his 350 titles in a winning streak which ran from 1968 to 1974.

The statistics of Giacomo Agostini’s career are quite staggering, particularly when viewed from the 1980s, when no rider has successfully defended a world 500 crown. Agostini once won twenty 500 grands prix in a row – that’s one more than Freddie Spencer won in his entire career! In fact Agostini’s records are such that they’ve tended to distort the way many people look at his career.

It’s quite true Agostini had world 350 and 500 titles largely at his mercy on the MV Agusta triples between 1968 and 1972. But there are a few points critics tend to forget. For a start, Agostini progressed in one year (1965) from Italian 250 Champion to within a whisker of dethroning World 350 Champion, Jim Redman.

Agostini won his first two world 500 titles in 1966-67 against Mike Hailwood. He won his last 500 title in 1975 for Yamaha against Phil Read (MV Agusta) and Suzuki pair Barry Sheene and Tepi Lansivuori.

“Mino”, as Agostini is known by friends in the MV days, was the last four-stroke rider to win a 350 world championship (1973), a world 350 championship round (the Dutch 350 TT in 1976) and a world 500 championship race (the 1976 German GP at Nurburgring). He was also the first two-stroke rider to win the world 350 title (in 1974) and world 500 championship (in 1975).

Giacomo Agostini beat Kenny Roberts to win the 1974 Daytona 200, in his debut both at the circuit and on a large two-stroke – Yamaha’s TZ700. It led to Kenny’s famed remark that “he didn’t beat me. I just came second, that’s all.” Agostini also headed Roberts in that year’s Imola 200 miler, after the latter cooked his tyres.

While Agostini and Graeme Crosby no longer share anything resembling friendship, they do share a record as the only people who’ve won the Isle of Man Senior TT, the Daytona 200 and the Imola 200.

Many afficionados can tell you Mike Hailwood (Honda 500-4) held the Isle of Man lap record outright from 1967 to ’75, and the 500 record until 1976, with a lap of 108.77 mph.

Agostini was number two in the fastest-ever IOM stakes throughout those years with a best lap in 1967 of 108.49 mph on the slower but better handling MV 500 triple.

Mike Hailwood reckoned Agostini would have won their classic confrontation in the 1967 Senior TT if the MV hadn’t broken its drive chain.

Agostini was the first world championship rider to sign a contract running to six figures in pounds or nearly $US250,000.

Giacomo Agostini raced at three meetings in Australia, on MV Agusta three and fours. He suffered defeats at two of those meetings – by Bryan Hindle (Yamaha 350) at Oran Park in 1971 and by Kenny Blake (Suzuki RG500) in the Australian 500 TT at Laverton Airbase in 1976.

So why are there Agostini detractors? His critics seem to fall into three groups. First are arch Isle of Man TT fans who’ve never forgiven Agostini for boycotting the TT after his friend Gilberto Parlotti was killed there in 1972.

Agostini’s action was the first step in the IOM losing world road-racing championship status.

Agostini’s stand ultimately did riders a big favour, by leaving Isle of Man participation to the individual rather than a necessity for world title points (the very reason world 125 title leader Parlotti rode there).

Graeme Crosby fans have no time for G. Agostini the race team manager, arguing that “Ago did the wrong thing by our Croz at the end of 1982”. I don’t propose to defend Agostini on that count.

The third group of critics (often Crosby fans as well) paint a dark picture of Agostini for making money out of the sport as a sponsorship broker. Sure, Agostini takes a slice of Marlboro’s motorcycle sport budget, just as Kenny Roberts does with Lucky Strike. People respect Roberts for it.

Agostini first rode for Marlboro in 1976. The company’s commitment now runs to backing a three-rider team in the world championships and building a huge base for the team, complete with dyno facilities and undercover parking for all the transporters, in Italy.

Marlboro’s arrival, with its accompanying publicity and promotion work, lifted the sport’s international image and encouraged rival companies to enter. Their investment saw them overtake oil companies as grand prix motorcycling’s major sponsors. The only non-tobacco company today matching this level of investment is Pepsi.

Giacomo Agostini had one major thing in common with Mike Hailwood – both were born into wealthy families. The difference was that Agostini’s father did not actively encourage Giacomo’s racing career.

Giacomo Agostini was born on June 16, 1942 at Lovera, near the city of Bergamo. He still lives in Bergamo and has based Marlboro Team Agostini there. Giacomo had three younger brothers, one of whom, Felice, raced during the 1970s and now works for his brother’s team.

Giacomo was, from childhood, fascinated with bikes. His father bought him a Vespa scooter at age nine and two years later a Bianchi moped, which Giacomo rode in gymkhanas. By age 15 he owned a Parilla, which he rode in trials events, and a Moto Guzzi 175 street bike.

Agostini Snr had a thriving transport and road-construction business. Giacomo drifted into the company on leaving school, but with little commitment. He took more and more time off for racing until, he says, he simply stopped working for his father. Young Agostini’s interest in racing concerned his parents. But they were sufficiently well-off to keep a young racer fed, clothed and housed, even after he stopped working for the family firm. Like Mike the Bike, Giacomo Agostini did not need family funding for very long. The boy from Bergamo was natural talent.

Agostini made his road-racing debut in 1962, on his Moto Morini 175. By the end of 1963 he’d won the Italian Junior Hillclimb championship on the 175.

Morini was sufficiently impressed by the end of 1963 to give 21-year-old Agostini a works bike for his grand prix debut at Monza. Agostini responded by running with the leaders until machine problems forced his retirement. It was enough to convince the. firm it had found an outstanding talent.

Agostini signed with Morini as a works rider for 1964, to fill the shoes of Tarquino Provini. It was a hard act to follow. These days Provini is justifiably famous for his bike models, but in the early 1960s he was one of the world’s best 250 racers. Provini in 1963 won four 250 grands prix on Morini’s brilliant twin-cam two-valve single, and went within two points of beating Jim Redman (on Honda’s 16-valve four) for the world championship.

Agostini in 1964 retained Morini’s fiveyear grip on the Italian 250 championship, beating Provini, who had switched to Benelli.

The name G. Agostini also appeared in the world championship results for the first time. Riding the Morini single, Agostini finished fourth in both the German GP at Solitude and the Italian GP at Monza, behind the three top guns of that year’s 250 championship – Yamaha’s Phil Read and Mike Duff, and Honda’s Jim Redman.

Agostini’s rides on the Morini impressed Count Domenico Agusta. The Agustas and their MVs had won the world 500 title seven times with British riders Surtees and Hailwood, but never with an Italian. Count Agusta signed the 22-year-old Agostini as understudy to Hailwood for 1965.

Giacomo’s signing with Meccanica Verghera coincided with a period of renewed racing development at Gallarate. There was a new three cylinder, 12-valve 350 to replace the four-cylinder eight-valve model which had served since 1957. Agostini concentrated on the new machine. Hailwood’s main goal was to retain his 500 crown on the MV 500-four.

The world didn’t have long to wait to see if Count Agusta had bought a winner. Agostini won the opening round of the 1965 world 350 championship at Nurburgring, beating Hailwood. He backed this up by finishing third in the 350 class in his Isle of Man TT debut, behind defending world 350 champion Jim Redman (on Honda’s 16-valve four) and world 250 champion Phil Read (on an over-bored works 250 Yamaha).

These first efforts were no flashes in the racing pan. Pundits had predicted Agostini would hurt himself. But when he finally had a high-speed fall, he walked away with a broken nose!

Agostini proceeded to run Redman to the wire in defence of his 350 title. The Italian won again at Finland and Monza. If Agostini could win the final round, the Japanese GP at Honda’s Suzuka circuit, he would be world champion in his first full grand prix season.

Agostini did not win. His MV-three suffered a broken contact breaker spring while he was holding a commanding lead over team-mates Hailwood and Redman.

The new MV man also did his job in the 500 class, by backing up Hailwood. He finished second to Hailwood six times and won the Finnish 500 GP, when Hailwood did not figure in the results.

Hailwood left MV at the end of 1965 to ride 250, 350 and 500 cm3 machines for Honda. Agostini was now MV team leader. The development engineers spent the winter “stretching” the 350 triple to become a 500 title contender. They took it to 420 cm3 and later to 489 cm3. The next two seasons produced sensational 500 grand prix racing. Honda was finally shooting for the premier title, with a brutally powerful 500 four. If the championship was decided on a dynomometer, it would have won hands down!

Former Australian international Eric Hinton described the difference in the two machines in terms of the MV being a racing motorcycle – properly finished – and the Honda being a racing engine slung between two wheels.

Honda further handicapped Hailwood by making Redman the lead 500 rider, for services rendered since 1960. This meant Hailwood didn’t get first choice of machines until three rounds into the title.

Redman won the first round at the lightning fast Hockenheim circuit, from Agostini. Hailwood’s Honda failed to finish. In Holland it was Redman from Agostini, and again no Hailwood.

The game play changed at SpaFrancorchamps, the world’s fastest public road circuit. Redman crashed his Honda and broke his arm. Agostini’s MV-three gave trouble during practice. He switched back to the old four and won in the rain. Hailwood’s Honda let him down again.

Both riders failed to figure in the results of the East German GP at Sachsenring. Hailwood’s Honda broke down and Agostini crashed out of the race lead at over 200 km/h, leaving him very sore for the following week’s Czech GP at Brno.

The next four rounds (all on public roads) in Czechoslovakia, Finland, Ulster and at the Isle of Man TT saw Hailwood and Agostini finish one-two to each other, with Hailwood winning the Czech, Finnish and IOM encounters.

It was now down to the final round at Monza. Hailwood’s Honda broke while leading. Agostini came home to a hero’s welcome – the first Italian to win the world 500 title since Libero Liberati (Gilera) in 1957.

Agostini, however, had to play bridesmaid to Hailwood in the 350 title. Both scored the same total number of points, but the title was decided on the best six results. Hailwood’s six victories on the 297 cm3 six-cylinder, 24-valve Honda gave him a perfect net score. Agostini was runner up for the second year running, with three grand prix victories and four second placings. One of those victories was also his first IOM win, and his first TT lap record.

Sixty-seven promised more of the same. Agostini and Hailwood turned on perhaps the 500 battle of the decade. With eight races run each had scored four victories. Agostini had won at Hockenheim, Spa-Francorchamps, Sachsenring and lmatra (Finland).

Hailwood’s victories included the classic Isle of Man battle, where both lapped at 108 mph before the MV broke its drive chain. Their duel at Assen was also well remembered. Hailwood won by five seconds.

The showdown was, once again, the Italian GP at Monza. Hailwood’s Honda let him down while leading. He toured in to finish second. Agostini won, to clinch his second successive world 500 championship.

Agostini and MV had for the second year shown that reliability and handling meant more than impressive figures on the test bench. The final scoreline for the season (including the Canadian GP) was five wins each. The winning difference was Agostini’s three second placings to Hailwood’s two. The 350 title was more of a Hailwood show. He won six rounds compared with Agostini’s tally of one win and four seconds.

The next major influence on the Agostini story was political. Honda withdrew from grand prix racing and paid Hailwood not to contest the world title rounds.

Agostini now had the world at his feet. MV knew it too. True to MV form, development on the 350 and 500 threes practically stopped until a new challenger appeared for both in the early 1970s. The only real problem was redesigning the seven-speed gearboxes and some tuning mods when the FIM cut the maximum number of gears allowed to six for 1969.

Eric Hinton reckoned the MV riders (Surtees, Hailwood and Agostini) were good sports to the privateers when there was no heavyweight opposition.

“Agostini would only go as fast as he had to. He might do one quick lap to up the lap record, then cruise. He didn’t want to make us look silly. One time Ago lapped me just as we took a corner leading onto a long straight. He pointed to the back of his bike and gave me a tow in the slipstream down that straight. Mike (Hailwood) and Surtees would do the same when they were out on their own,” Hinton said.

Off the track, Agostini’s good looks made him a movie star in Italy. On the track Agostini probably wanted competition as much as anyone. He welcomed competition from former world 125 champion Bill Ivy in 1969 on the Jawa 350 V-four two-stroke. Ivy led Agostini for a while in the ’69 Dutch 350 GP. Two weeks later the Czech machine seized during practice at Sachsenring and Ivy was killed.

Hailwood biographer Ted Macaulay described Agostini at the time as a Latin with a non-Latin temperament. A man with an easy, friendly smile and a confident but not conceited air, and uncharacteristic cool.

But 1972 produced something to spur interest from Agostini and MV. The spark, for the whole racing world, was Finn Jarno Saarinen and his 250 and 350 Yamahas.

Saarinen’s three 350 grands prix in 1972 were the most races an opponent had taken off the Agostini/MV show in one year since 1967. He also won the world 250 crown.

Late in the season MV added some more spice, by offering machines to Britain’s former world 125 and 250 champion Phil Read.

Yamaha came out guns blazing in 1973, with Saarinen and Hideo Kanaya riding new in-line four-cylinder two-stroke 500s. MV countered by building a new 16-valve four-stroke four and hiring Read as Agostini’s team mate. Germany also provided a title threat, in the flat-four two-stroke Koenig, ridden by New Zealand’s Kim Newcombe.

Saarinen won the first two rounds and broke a chain four laps from the finish of the German GP, after a big dice with Read on the new MV-four.

Agostini meantime had failed to score a point in his title defence. He had wet electrics and/or a misted visor in the wet French GP, and DNF’d with mechanical problems in both Austria and Germany.

Students of the Read/Ivy battles at Yamaha in 1968 will know Phil Read played the game of team mate very hard. By round three he’d got under Agostini’s skin and convinced the MV management to give him the new four, after Agostini crashed it during practice in Austria. Agostini did better in the 350 title. He won two of the first four rounds, the second victory coming on the new 350 four.

And then the whole game changed again. Saarinen and Renzo Pasolini were killed on the opening lap of the Italian 250 GP at Monza.

Saarinen’s death absolutely devastated the racing world. He was seen as the most exciting new champion in years. One commentator rightly said Saarinen had lifted motorcycle racing by his very presence.

The 1973 500 title went into a temporary neutral. The Italian 500 GP was cancelled, and the works riders boycotted the Isle of Man (won by Australia’s Jack Findlay on a Suzuki twin) and Yugoslavia (won by Newcombe). Read then won at Assen from Newcombe. Agostini retired with his bike jumping out of gear. The seven times world 500 champion had failed to score a point in six rounds and four starts!

Agostini’s 1973 500 effort gained respectability at Spa-Francorchamps. Even Read said the Italian was in great form. The Spa and Brno results read Agostini first, Read second. But the points situation was hopeless. Read’s victory over Agostini in Sweden gave Read his first 500 crown and Britain its first since the Hailwood days. Kim Newcombe, who was killed soon after, was second in the title and Agostini third.

The 350 title series was more rewarding. Agostini scored four victories and two second placings to beat Finn Tepi Lansivuori, who won three races on his works Yamaha.

The off-season brought a sensation for Italy’s racing fans. Agostini signed a contract for one hundred thousand pounds to ride for Yamaha. Rod Gould, who did much of the arranging, said it was money well spent. Agostini was a professional – if he was required for a function you could be sure he’d be there, in a suit, and properly representing the company. Agostini also made a personal sponsorship arrangement, albeit modest at first, with Marlboro.

Giacomo Agostini began his Yamaha career in style. He won the Daytona 200 and Imola 200 on the sensational new TZ700 and beat Read at Modena (Italy) in the first 500 cm3 clash of the season. The other pre-championship 500 encounter saw Read win by half a length, after an elbow and fairing rubbing duel. The first grand prix start, in the 350 class at Clermont-Ferrand (France) bought another Agostini victory.

It was to be an Agostini year in the 350 class, with five victories and the world title. The 500 class was a tougher proposition. Agostini’s 500 broke down while leading in France, so Read won from Barry Sheene on the new square four Suzuki.

Agostini won at Austria, then ran out of fuel two laps from victory in the Italian GP at lmola. Yamaha’s Agostini and Lansivuori enjoyed a one-two win over Read in the Dutch GP. But Read struck back to win at his favourite high-speed circuit, Spa.

Agostini’s title chances came completely unstuck in the Swedish round at Anderstorp. Sheene’s Suzuki went sideways at the end of the straight on the first lap. This triggered a melee which saw Agostini run off the track and crash into the catch fencing.

Injuries kept Agostini out of the next round in Finland. Read won and wrapped up the premier crown for the second time, after a battle with Lansivuori. The final title placings were Read, Gianfranco Bonera (MV), Lansivuori and Agostini.

Yamaha put renewed effort into the 1975 title series. Contrary to popular opinion, its machine wasn’t the fastest – that honour belonged to the MV for top speed and overall to the new but fragile Suzuki.

The Yamaha’s advantage was its rideability. It had piston-reed valve induction and cantilever rear suspension. Yamaha, thanks to a patent it bought from Belgian inventor Leon Tilkens, had reversed the accepted ideas of a decade before. Japan was now showing the Italians something about suspension and chassis technology.

Agostini and Hideo Kanaya opened the 500 season with a one-two over Read in the French GP at Paul Ricard. Agostini then DNF’d in Austria, where Kanaya and Lansivuori (Suzuki) pushed Read back to third.

Agostini won again at Hockenheim, beating Read in the best race of the year. Read at one point pulled a slide of 100 metres at over 200 km/h. Agostini won at lmola, then Sheene, recovering from his huge Daytona crash, found some reliability with the Suzuki 500 and beat Agostini at Assen.

Read fought back at Spa, riding the race of his life to win. Agostini failed to finish. Another very unusual DNF by Agostini in Sweden gave Read a last crack at the title. The Yamaha rider suffered a flat front tyre and crashed. Sheene won from Read.

Luck went the other way in Finland. Agostini won, to become the first rider to win the 500 championship on a twostroke. Read suffered a broken magneto.

The 350 championship was another story. A new star, 19-year-old Italian-born Venezuelan Johnny Ceccotto, had emerged. He beat the works Yamahas in both the 250 and 350 classes in France. Ceccotto won three more 350 championship races during the season, to take the crown Agostini had held uninterrupted since 1968. Agostini won just one 350 GP in the whole season.

Yamaha was so impressed with Ceccotto it signed him for 1976.

Giacomo Agostini formed his own team, backed by Marlboro, to run 350s, 500s and 750s. He had the MV 350 and 500 fours, and a Yamaha 750. It was a disjointed year for the 15-times world champion. Marlboro reportedly wanted him to contest as many meetings as possible.

In 1976 Agostini brought the magnificent noise of the MV 500-four to Laverton for the Australian TT. Stu Avant led until his Suzuki RG500 seized, then Kenny Blake (also on a new Suzuki) passed Agostini and won.

The lesson of being beaten by a virtually out-of-the-box two-stroke can’t have been lost on the champion.

Agostini contested the first two 500 championship rounds on his MV, finishing fifth and sixth. Barry Sheene meantime was running away with the title on his works Suzuki. So Agostini bought his own RG500 and took pole position for the Italian GP at Mugello.

The race saw a three-way battle for the lead – Sheene versus the “production” Suzukis of Agostini and Read – until Agostini’s machine suffered mechanical problems.

Italian and four-stroke pride had two great moments in the season. Agostini won the Dutch 350 GP on the MV-four by 24 seconds from French Yamaha ace Patrick Pons. Two months later, Agostini used his circuit knowledge and the MV’s smooth power delivery to win the German GP in the wet at Nurburgring. He beat two men of the future – Marco Lucchinelli and Pat Hennen on their Suzukis.

These were the last four-stroke grand prix wins, and pretty much Giacomo Agostini’s last real fling. He was 34 and had done it all.

Agostini secured works Yamahas for 1977, but could only manage sixth place in the world title, beaten by the works Suzukis of Sheene, Hennen and Parrish, and the works Yamahas of Steve Baker and Ceccotto.

Agostini’s best 500 ride of the ’77 season was the French GP, where he finished second to Sheene and set fastest lap, nearly a second under Baker’s best time in qualifying.

Seven-fifty racing proved a happier hunting ground. Agostini was third in the inaugural World F750 Championship on his works Yamaha, behind Steve Baker and Christian Sarron. The Italian had a good second to Baker in Austria and won the final round of the series at Hockenheim on September 18. It was his last major victory.

Giacomo Agostini, the man who entered grand prix racing with such a splash, faded out of it with some nondescript rides in 1978. He turned to car racing, without the success he enjoyed in bikes – perhaps because he switched so late.

He returned to the sport in a new capacity in 1982 – running a world championship Yamaha team with Graeme Crosby and Graziano Rossi, and Dave Cullen heading the mechanical team.

Crosby won Daytona and Imola (as his boss had 12 years earlier) and finished second in the world championship. The following year Crosby and Agostini “fell out”. Agostini’s team became the works Yamaha team, with Kenny Roberts and Eddie Lawson as riders and Kel Carruthers as head technician. The team has since claimed two world championships.

By Don Cox. Two Wheels, September 1988

Circus Life is Don’s account of the exploits of a bunch of young Australian motorcycle racers who followed the GP circuit as privateers through Europe in the 1950s. It’s beautifully written, forensically researched and accompanied by some amazing photographs. Don discusses Circus Life with Jay Leno on Jay Leno’s Garage here, and you can order a copy of Circus Life here.