Once Upon a Time on a Mountain

Of the hundreds of competitors at every Bathurst meeting, maybe a dozen leave the place with memories they’ll always treasure — images that are dragged out over pots of ale and around crackling fires, when the company’s right.

Picture this: You’re spectating on the bluff above the Dipper, forearms resting on the inch-thick wire rope that forms the top strand of the fence. The crowd has thinned. “It’s only a B-Grade race,” they say. But you’ve seen five and a bit laps of cut and parry, pass and be passed. To begin, four were in contention, but for the last couple of laps just two runners, riders whose names are unfamiliar to you.

Closing phases now. In the distance two bikes round Hell Corner, at most a length apart, and head towards the Mountain. One “towing” the other, they seek the crest of Mountain Straight, then plunge into the trees near XL Bend, before hiding under the Mountain’s skirts.

You wait. Seems a minute; in truth maybe 20 seconds. Finally the commentator at Skyline heralds the pair’s entry to the huge amphitheatre bounded by Reid Park and Skyline.

“There are the leaders now, through the trees near Griffin’s Mount…

“There’s not much in this … And as they go over The Skyline it’s nose to tail … A nice line by the two leaders down through the Esses…”

Two machines curl into view, virtually at your feet, using the same hand-span width of tar. Delicate braking to set up for the Dipper.

Through the spoon-like dip and away… power on; the second engine mimics the first. Kink right, under the trees, kink left; power off, brakes, kink right; and disappear toward Forest Elbow.

Another wait. Then down on Conrod: Two bikes, line astern, clinging to the road as they spear past the orchard and the drive-in gates.

An authoritative, precisely modulated voice assumes the commentary for the last 500 metres of the race, as you watch two specks streaming up to the last hump.

“The leader breasts the last hump, front wheel high again; still shadowed …

“Into the braking area; there’s a challenge! He’s closing down the outside!”

From over a mile away you see the specks merge.

“It’s anyone’s race, the fairings must be touching now! Fifty metres to the corner … The inside bike peels off first; I think he’s got it. He has the line for the corner … Both on the power now…”

From the Esses you can make out one bike passing the apex of Murray’s about a length clear of the other. They seem to crawl out of the corner.

“Yes, a win by two lengths at most! What a race! The early race leader will be a comfortable third.”

If the two jousters were permitted a slow-down lap, you’d offer them applause. Instead they turn into Mountain Straight and are waved into the back gate of the pits.

And perhaps you turn to your mate and say: “Good race. You’d be rapt to win a race like that, wouldn’t you!”

Up on the Mountain, or even as a day-tripper at Murray’s or Hell Corner, you see and hear the memorable moments of Bathurst.

But if that’s the elation of Bathurst, the handful of competitors in the same race who’ll know real disappointment will know it privately. The stories of what might have been are not for the spectator to know, unless you cross the James Hardie bridge and happen on a tent where a machine is in pieces or a rider is packing up early.

Likewise, only on the paddock PA system would you hear a message like: “Does any competitor have a set of Yamaha TZ350 crankcases? Would you please see Peter McKay at the secretary’s office. A set of TZ350 crankcases.”

To hear that at 10.15am on Easter Friday is to think: “Well, one rider’s weekend is quite likely over.”

Serious TZ racers pack spare cylinders, heads, complete cranks (with main bearings and conrods), pistons and oft-times ignitions for every meeting, the way US tourists pack cameras and floral shirts. But crankcases? The most likely reason for having two sets is that the first set is ventilated.

As the announcement is made, Adelaide mechanic Trevor Otto is at the Murray’s Corner end of pit row, monitoring the progress of Australian 500 Grand Prix contestant Kym Colbey. He ventures to the Colbey crew: “I’ve got three sets of TZ cases at home!”

Not a minute later Team Colbey has a visitor. Still in his blue and yellow leathers, Peter McKay is sifting through the crowded pit bays; maybe somebody knows somebody else who has some cases. As a South Australian now resident in Wollongong, Peter knows Trevor as one of the game’s more knowledgeable and approachable wrenches, and pauses for an exchange of greetings.

“Broken a rod?” asks Trevor.

“Yeah, going into Hell Corner. Nearly pitched me off,” Peter says. “I’d just rolled the throttle shut and it went bang!”

It’s hard to believe so much damage could be done so quickly, in that fraction it takes a rider to pull in the clutch. But the flailing rod has smashed a hole through the front of the crankcases and sheared one half-moon spiggott clean off the bottom of the cylinder.

“I was just saying I’ve got three sets at home,” Otto explains, with resign and a dash of apology in his voice. “Oh, I have a new crank for you, the one Peter Williams owes you from the Sandown meeting!”

At this point McKay probably could have been excused for feeling a thump in the bottom of his stomach, and wished he’d bumped into Otto about 15 hours earlier.

It turns out his broken conrod was not the first drama of the weekend. He related how the previous day a brand new crankshaft lasted just eight laps (a session and a half of practice) before a big end seized at the top of Mountain Straight. Peter hunted around for someone with a new crank, but nobody he asked had a spare one.

“I didn’t want to rebuild the motor with an old crank; but I had nothing else. Then just this morning a guy came up and said he had two new cranks!”

For later reference Peter asks Trevor where Team Colbey is parked, then heads off.

Six and a half hours later, in the very last solo practice session, a blue and yellow streamlined TZ350 wheels around the bluff and into the view of an impatient group of shivering flag marshalls at the Dipper, the exhaust note deflating as the bike is braked hard for the dip. A crack of power out of the Dipper, a quick wheelie before the swing right and the power-on rush past the Toombs memorial stone, then out of sight.

Peter McKay is back in action.

Four laps later, four laps of two fingers on the clutch lever, thinking a locked up engine and consequent locked rear wheel could come in threes, and practice is over. No practice times have been taken; no qualifying time for the 500 GP as Peter missed the session; no time to try taller gearing than he used last year. But McKay has a motorcycle that’s running and run-in.

If you go looking for the heart and soul of Bathurst racing, it’s often beyond the well-publicised names, in riders like Peter McKay. Riders who camp in the pits, would lend their closest rival a needed part, enjoy a beer around a campfire when the work is done for the night, and look for success in their graded race with some “cream” in a top-ten place in one of the feature events.

Last year Peter had just been upgraded to B-Grade at Easter. He placed seventh in the 350 B-Grade, 11th in the up to 1300 B, couldn’t persuade his bike to start for the 350 GP and was running eighth in the glamour 500 GP when his bike blew a big-end bearing as he was going through the Cutting.

He’s a steady improver, not a “flash” or a crasher. In contrast to many of today’s coming men, he’s not from the talent nursery of mini-bike racing. Recent results include a good fifth in teeming rain in the final round of the 1981 Australian 500 road race championship at Sandown Park. Then two weeks before Easter, Peter was sixth in the opening round of the Australia 350 series at Symmons Plains, Tasmania, and won the 350 B-Grade race at that meeting.

Bathurst ’82 sees Peter rated in the top three contestants for the 350 B grade. The organisers have given him grid position two. But that rating was made weeks ago. It takes no account of dramas in practice.

But the anxious call for a set of crankcases has been answered by a keen rival for B-Grade honours, Steve Mapperson.

More good fortune appears with help in the second engine rebuild from Harry Nicholl (father of last year’s 350 B winner Terry Nicholl) and Queensland racer Wayne “Stringbean” Jenkins. Their assistance was the difference between finishing the job in time for those four laps of vital bedding-in, and working into the night. Peter said one of the hardest parts of the 11pm Thursday effort was the procession of about 20 people who all wanted to offer him a tinnie!

Saturday morning is the first occasion in the weekend Peter has time to himself. While the hot rods roar away in search of a finish in the Arai 500, it’s housekeeping time in the McKay pit. He’s set up in a quadrangle with Ducati aficionados Ian Gowanloch and Arthur Davis, and their riders Chris Nankivell and Peter Muir. They’re all on duty for the Arai. A glance at the Marzocchi forks and Brembo front brakes on Peter’s mount shows the connection. Ian’s firm imports these items, while Peter has had a few rides on Arthur’s Ducati superbike.

Barely ten paces away from the four-metre-square McKay tent is the tent of Wollongong clubmate and (next to Mapperson) Peter’s main rival for 350 B-Grade honours, Ron Sumskis.

The McKay tent displays a sense of organisation. The tent is for the bike and cooking and the Hi-Ace van is the bedroom. Tent lighting is fluorescent: When you’re a leading hand electrical fitter on a coal loader project at 24, you can come to terms with employers for lighting equipment for the year’s biggest meeting, and you can also come to terms for time off to race.

It’s more than two hours to race time for Peter, but his machine is ready to roll, save for mixing the fuel. However, he plans to roll the bike into the tent about an hour before start time to look over it again.

Peter bought his machine from sponsor Karl Praml, a Kiama and Oak Flats motorcycle dealer who previously nurtured the talents of Wayne Gardner and Wayne Clarke (who finished third outright in this year’s Arai 500). Under the sponsorship agreement Praml supplies all the bike’s requirements, except tyres. Free tyres are the carrot if Peter is promoted to A-Grade.

The Arai is two-thirds run; there are some visitors to Peter’s tent. Terry Kelly, who’d be next to unbeatable around Queensland’s Lakeside circuit on a 350, drops by. On the comeback trail after a few years in semi-retirement, Terry has just junked his third new crank in three meetings. A spark plug dropped an electrode. It’s gone through the piston and left swarf in the big end.

Thinking of his own engine, Peter confides: “I just hope my motor holds together for today’s race. I have good grids for the B-Grade races. Front row grids make a lot of difference here because it’s easy to get baulked at the start and the first corner.”·

One o’clock comes and goes. Team Gowanloch returns from the Arai. Chris Nankivell’s ride on Davis’ superbike has been spoiled by a broken battery connection and ignition parts that keep trying to jump overboard. Perhaps the bike knows what cost Mike Hailwood fourth place in the ’79 Formula One TT – the battery falling out of its mount. Gowanloch flashes a mock finger of scold as Peter mixes his fuel: “I don’t want to hear a word out of you McKay!”

Two o’clock.

A typically hectic 250 production race is still being decided when the riders are called up for the 350 B-Grade. Peter is already dressed for battle.

At last the seemingly indispensable two-tone blue Marzocchi cap comes off. With helmet and gloves donned, he rolls the TZ off its stand, aims it downhill, slips astride: A strong step with each foot and a flick out and back with the clutch prompts the engine to life.

When the gate opens onto the circuit, Peter tries to clear the engine in the 100 metre run before the grid marshals want all engines cut. Roll up to grid position two, stay astride, visor up, and wait. The grid is cleared at the two minute board. One minute; thirty seconds; they’re in the starter’s hands.

Flag up. Eighty booted feet paddle start forty Yamahas. Peter is away well and third at the top of Mountain Straight, behind Mapperson and Sumskis in a Wollongong derby expanded to a foursome by last year’s fastest C-Grader at Bathurst, Geoff McNaughton.

On the Mountain Sumskis hits the lead for a moment only to be repassed by Mapperson. McNaughton, riding like a man possessed according to Sumskis, takes McKay at McPhillamy, then Sumskis. But on the straight McNaughton seems to lack power, so at Murray’s Corner the order is Mapperson, Sumskis, McNaughton and McKay.

Then comes a telling second lap. Over the hump in Mountain Straight the four riders form a fighter wing formation – two side-by-side pairs, the second pair behind and diagonally to the right. Into the XL Bend braking area they’re almost abreast, with Mapperson a little out of shape, but taking the corner first. And then McKay strikes.

He passes McNaughton at Forest Elbow, gets Sumskis down the straight and outbrakes Mapperson at Murray’s.

Lap three: McKay leads up the hill, chased by Mapperson, Sumskis and McNaughton. Eleventh placed Rod Price is decked at XL by a seized engine and run over by Grant Maguire, who also falls. Price suffers rib injuries. Another rider’s weekend is over.

On the same lap Sumskis annexes second place from Mapperson then outbrakes McKay to take the lead at Murray’s. “After that we left Steve and Geoff and started our own dice,” Ron explained later.

It’s Sumskis in the lead for most of the fourth lap, then McKay challenges successfully again at the foot of Conrod to lead off on the second last lap. He holds the lead going into the last lap, being at most three lengths ahead on the ascent of the Mountain. Across and down the Mountain they’re even.

Onto Conrod for the last time, McKay still leading. It’s all down to the last corner for Sumskis, and coming over the last hump into the braking area he sees his chance .

“Peter appeared to brake early for the last corner. I thought that was my chance, but I was on the outside. He had to move over to get his line for the corner. You couldn’t have got a feeler gauge between our fairings … but I had to follow him to the finish line. I learnt something: Brake on the inside!”

Back at Peter’s pit Team Wollongong is together and it’s congratulations all round.

“Rapt! I needed that one,” says Peter. And turning to Ian Gowanloch: “Oh mate, this makes it all worthwhile. The forks are magic. Through McPhillamy, it doesn’t patter or anything!

“That’s the one I wanted to win. Two hundred and seventy-five bucks. Wish they paid that every weekend. I’m rapt. And it was faster than Ron’s.”

Two hundred and seventy-five dollars. For the moment it doesn’t matter that the cost of contesting the meeting must be heading towards $1000.

Ron Sumskis drops by. “I really enjoyed it. We were dead even across the Mountain. Oh, Peter got into some big wheelies over the last hump.”

The news comes through as Peter is hauling off his leathers that he’s broken the 350 B-Grade lap record. which has stood since 1979. Ron is glad that Peter’s got it, being only 0.1 second off equalling the old record himself.

With his next race at 11.40 the next morning, an adjournment to the licensed marquee in the paddock is appropriate. Over a beer or two Peter reveals his beginnings in the sport, a sport he wanted to participate in since his early teens; a sport he thinks is the best in the world.

Raised in Port Augusta, Peter learned to ride on BSA Bantams, spending his out-of-school hours in the scrub rabbiting. At 16 he had a road licence and was already an avid road race fan, though he’d never been to a circuit. He just read lots of magazines and books.

Then one Saturday when he was 17, he rode to Adelaide to buy an exhaust for his roadgoing Honda. Outside a bike shop he saw a second-hand TZ350B for sale. The money for the exhaust made a deposit. He was back a week later with his father’s utility and soon practising at Adelaide raceway. John Clarke and the late Ian Lowe helped him early on, and Peter bought Ian’s TZ350D just before moving to Wollongong in 1979.

Living in Port Augusta was restricting the number of meetings Peter could do in a year, so he planned a move with his girlfriend Alice, a nurse.

What’s the most asked question of this weekend? “Where’s Ali?” Alice usually attends meetings, but this weekend she’s representing Peter at his brother’s wedding in South Australia. Peter says he’d like to have been there, but his brother understands how much Bathurst means to him.

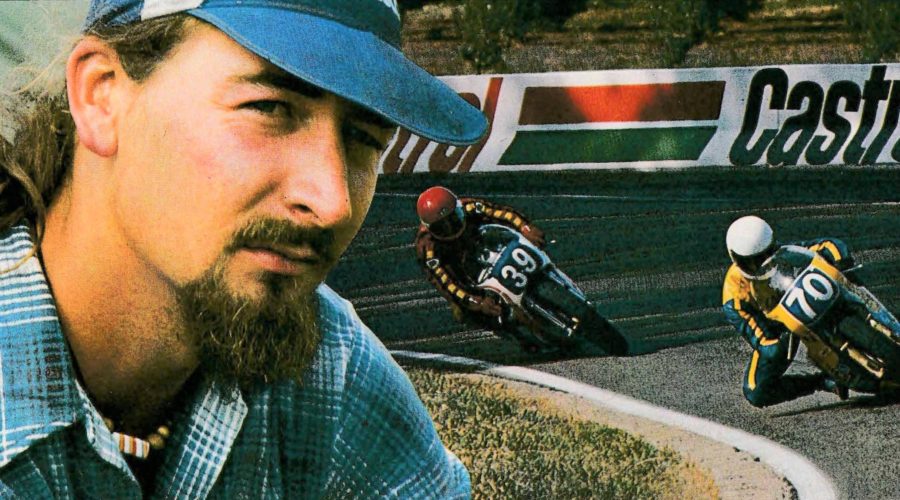

With his strong face, Leninish goatee beard, hair raked back under that cap into a short tightly plaited pigtail, Peter cuts a striking figure in the pits. The afternoon is dispersed with comments of “good ride” from passers by.

Late Sunday morning it’s back to action again. From a second row grid position in the Australian 350 Grand Prix, Peter makes a fine start and is sixth at the end of the first lap.

After four laps he’s caught and passed Gary Gleeson, but is still sixth as 250 GP winner Chris Oldfield has passed the pair of them on his KGM-Rotax 250. Peter strives for the remaining four laps to get close enough for a challenge to Oldfield. But he appreciates it’s the difference between a seasoned A-Grader and a potential A-Grader at work. Every time Peter closes at the end of a straight, he has to admire Oldfield’s ability to set himself up for a quick exit from a corner.

Oldfield and McKay finish fourth and fifth, less than two seconds separating them. The top six placing means a trip to the scrutineers bay to have the engine sealed.

The scrutineers bay is packed out with machines from the Unlimited and 750 Production race, the entrants and riders haggling about whether the proddie bikes will be stripped and examined on site or taken back to Sydney. Peter is buttonholed by someone acting as runner for Ron Sumskis. Ron has broken a gear selector shaft. Without hesitation Peter tells the runner where to find a spare one.

After a delay in having the official measurer affix the seal, there’s no time before the Unlimited B-Grade to pull out the rear wheel and gear the bike one tooth taller. But before he heads to the dummy grid for the race, Peter arranges Sumskis’ runner to mix fuel for the 20-lap 500 GP and for Arthur Davis to be on hand to check brake-pad wear before that event.

From the front of the Unlimited B grid Peter fires into Hell Corner in second place. On the top of the Mountain he takes the lead. But down Conrod he’s swallowed by the 1100cc superbikes and late brakers. It’s a bun-rush of six bikes into Murray’s Corner. And then it happens…

Newcastle rider Ian Standen comes sailing down the inside on his Suzuki Katana 1100, gets crossed up and nearly highsides, saves it, clips Steve Mapperson’s rear wheel and centre-punches Peter. The TZ flips straight over onto its right hand side and two riders go sprawling across the road to the edge of the sand trap. Mapperson stays upright.

Peter is helped to his feet and taken to the armco, where he sits and watches Sumskis snatch third place after a good duel with McNaughton. Standen offers a cursory “Sorry, mate”, but that doesn’t get a bike fixed. It’s the first time in its two-year life that Peter’s bike has been down the road.

There’s superficial damage, but no chance to clean it up in 20 minutes before the 500 GP and Peter has a sore left leg and shoulder.

Peter’s meeting is over, race wise. The afternoon he spends chatting with former Isle of Man racer Harry Nicholl and anyone who drops by to ask what happened. In the evening there are campfires to visit, but he stays mainly around the Ducati crew’s fire; army great coat on and still in the cap, having a few cans without any haste. By 10 pm he excuses himself and hits the sack.

Next morning the paddock has thinned out. The left shoulder is nagging. Peter tracks down Chris Oldfield with the money for a new fairing, already thinking he can repair the existing one and so have a spare. The Hi-Ace van is packed. By noon Peter is on the road home.

Six weeks after Bathurst the word is official. Peter McKay has been promoted to A-Grade, along with Ron Sumskis.

At Bathurst next year somebody’s going to look through the lap records page of the programme and see 350 B-Grade; year 1982; time 2m 26.05s; average speed 152.19 km/h; holder Peter McKay (NSW); machine Yamaha 350.

And they’ll think … He had a good Bathurst.

By Don Cox. Two Wheels, July 1982

Tribal Rites on Saturday Night

The ball of red heat drops slowly below the western hills, setting the low clouds aflame with lances of fire. In the valley below, the lights of the township are already flickering, spreading up the valley like a sequinned tongue, a little more every year.

The lights in the camping ground are also ablaze. A hundred metres to the left of us, a Eureka Stockade Southern Cross flutters slowly in the light breeze, while overhead, the Southern Cross proper stands guard over the glorious Mountain as its children go about their annual business.

It is Bathurst, Saturday night at McPhillamy Park. Hundreds of bonfires burn bright orange holes in the descending darkness. To the townspeople below, we must look like Attila the Hun’s invading hordes, camped on the mountain in preparation for the morning’s pillaging.

A Harley Sturgis blats past our camp, three-up, throwing a tail of red Bathurst dirt to the sky. The sounds of other big four-strokes being punished over the rough back-roads ricochet around the mountain. We are roughly 10,000 strong.

Some of us are tradesmen, others businessmen. A percentage are unemployed, some are rich. Our machines reflect our varied personalities, There are Hondas and Harleys, Laverdas, BMWs, Suzukis, Triumphs, Nortons, Ducatis, Yamahas, Kawasakis, Benellis, Bultacos and BSAs. There are cafe bikes and cruisers, touring bikes and commuter cycles. There is little rivalry between makes, personalities or theologies. We are, after all, united by a very strong bond.

”Freshy”, one of the enthusiasts at our encampment, has one word for this bond: “Bathurst”. He often looks up from our fire, peers out into the clear, cool darkness across the valley, takes a deep breath, and lets the word escape from his lips with the reverence of a heartfelt prayer and the precision of a smoke ring.

An air of expectancy hangs over the mountain. Food and drink is being consumed, along with a number of less legal delicacies. The campsite on the opposite side of the road is playing AC /DC full blast while they rev a CB900 to 10,000 rpm, drop the clutch, and fill one of their tents with Bathurst dust. Between our camps, two riders on Yamaha twins are playing “chicken”. After several close calls, the game ends when one falls off his bike and rolls about on the ground, laughing hysterically.

The full moon has risen and the werewolves of Bathurst come out. Within minutes, the circle is formed around a guy on a big Japanese four. He holds the throttle open for two minutes and the rear wheel throws heavy clouds of dust into the air, making it impossible to breathe or see. Around the· circle, hundreds peer into the suffocating dirt, waiting for the engine to seize or explode. It does neither.

Suddenly, the screaming sound of thrashed pistons and valves stops as the crazy at the controls decides his engine has had enough. He blips the throttle to let everyone know his bike hasn’t eaten itself, and a rousing cheer of appreciation goes up. Someone comments: “Bathurst must keep Australia’s motorcycle spare parts industry alive for at least six months.” The circle parts to let the bike and its rider escape.

There are shouts for more action and an outfit which has been lying dormant beside the tree in the centre of the ring, roars into life. The three-wheeler zig-zags across the circle, picking up the outside wheel, then sliding around to face the opposite direction. A cloud of thick dust moves off with the prevailing breeze, like a pall of mustard gas.

The crowd cheers for more. The sidecar pilot revs up his machine and charges the tree on centre stage. He misses it by millimetres and wheels the sidecar about once again to the hearty approval of the crowd. He then turns the bars full lock and dials in the power. The outfit responds by doing doughnuts, but no-one can see anything through the clouds of cinnamon-coloured dust. The noise stops and someone runs from the circle and jumps onto the three-wheeler to act as passenger. He lasts about three seconds as the sidecar spins around and flings him heavily to the ground. The outfit comes to a stop, smoking profusely.

Not to be outdone, a guy on a Z1000 announces – by revving his bike to destruction point – that he’s about to do something worth watching. He is going to do doughnuts while towing someone behind. The motor seems to be working on two cylinders and it stalls once the tow rope takes the strain. The bike and its rider fall over and five or six onlookers race from the circle to help them up for another attempt.

He tries again and again but keeps falling over so attention switches to a barefooted, T-shirted guy climbing a telegraph pole inside the circle. He shimmies to the top and the crowd is delighted with his success, but there is more interest in how the hell he is going to get down. “Sarge” next to me quips: “This crowd won’t be happy unless he falls”. A roar of delight goes up as the Z1000 rider finally tows his mate out of the circle, and heads off down the hill at about 60 km/h, like Achilles dragging a dead Hector round the walls of Troy.

A few others bring their bikes into the circle, the most successful being a big Laverda Jota which performs about eight doughnuts without losing its rider. Meanwhile, the guy on top of the telegraph pole slides down on his bare feet and forearms at an alarming rate. Contenders with bikes become fewer so several guys fall to the ground and perform doughnuts by pivoting on one arm while they run round in circles in the dust. This “dance” would go down well with Russian Cossacks. Then several couples stage a mass piggyback fight.

The war escalates until one passenger falls heavily, breaking his ankle.

“Could’a been his neck,” says a bystander who heard the crack. There is no aggro in this crowd, just a lot of very dusty guys keeping themselves entertained.

Up and down the access roads which criss-cross McPhillamy Park, there is a constant stream of activity. Bikes howling along completely sideways but more or less in control, others motoring sedately, one-up, two-up, even five-up. Others are towing “skiers” who slide along the gritty roads on the soles of their boots or on bits of cardboard.

There is a party atmosphere outside the brightly-lit police compound. There are said to be 245 police up here, including a specially trained riot squad. The only rioting here is done by a few members of the force who are laughing uproariously at a private joke. Most of the older police are mingling with the crowds. The younger ones are inside the fenced enclosure and they seem to be waiting for something to happen. Nothing does.

The riot sticks which each policeman carries seem totally unnecessary and out of place. There are rumours that one policeman was hit by a beer can last night and that batons were drawn in retaliation. There is no evidence that anything like that will happen tonight. Still, the police aren’t taking any chances.

An announcement comes over the public address system: “We’re told there is an electrical fault and that the lights may go out. Don’t panic, it’s Just a fault. I repeat…” The police obviously feel that light is the only thing that protects them against this chain-wielding, raw meat-eating mob of Marlon Brandos. Take away the light, and all hell will break loose. The blackout never comes and the party rages on.

The day begins at 6am for most. Many of the fires are still burning and there are a few brewing coffee and tea. Most are nursing hangovers. In the valley below, a thick, white mist covers the township, all except for the spires of the church which spear through the cotton tufts. Everything is quiet. No bike noises, just still, virginal mountain air.

All our gear has been left out overnight. The helmets, food, jackets, cooking utensils and even the mull, are undisturbed. This is Bathurst. You don’t have to lock your car, hide the keys to your bike or bury the piss. Nothing gets stolen. It is a weekend of peace, love and motorbikes. Sure, we play rough, but so what? We’re here for the racing and our own special breed of entertainment. Bathurst has been ever thus, and will remain so while at Easter time they hold motorcycle races on the Mountain.

By Dave Kent. Photos by Frank Lindner, Graham Monro and Khan Denis. Two Wheels, July 1982