Mr Smith: Maintenance? It’s a Cinch

There’s no doubt about it. I’m a typical tradesman.

Well, it’s not that I’m a real tradesman. I left the Fixing Things business shortly before The Powers That Be declared it compulsory to possess the State Letter from Dad allowing me to wield a spanner and, in that time of industrial transition, all I would have had to do to obtain same was ask for it, but I didn’t.

However, I am still fairly typical of mechanics. Just about nothing I own works and I find I am not particularly motivated toward repairing anything. Oh, I’ve slowly accumulated swags of the appropriate tools and I could just about refit a capital warship with the stuff I have lying around the Maison De Smith but ‘struth, what’s the value in it?

The Immutable Laws of Mechanics always prove an almost insurmountable obstruction and tend to propel me toward the abyss of psychological collapse. To illustrate, let me tell you all about what happened when I attempted to change the oil filter on my new cycle, Rhonda the Honda.

I mean, it all seems so simple. The oil filter on Honda fours protrudes from the front of the engine like a schoolboy’s, er, ruler. There’s a 12 mm bolt head on the end of the fancy oil regulating tube that holds the whole shebang together. Looks like no wukkas, so out with the 12 mm socket (I operate under the great Francis Beart’s First Rule: No Open-Ended Spanner Will Ever Touch My Machinery!) and on she goes.

The requisite quantity of pressure is applied via sliding T-bar … and the socket turns on the bolt head, stripping the points from same. Aha, Rule 62: If it looks solid, it’ll fail.

No problems, it merely means that a different approach is necessary. I remove the exhaust system, which is hampering progress, and proceed to carefully file the bolt head down to fit an 11 mm spanner. I decide that, since sockets do not provide direct radial tension upon bolts, I shall utilise a long-handled Stahlwille (my favourite hand tools … they feel great in the fist) combination spanner with, naturlich, the ring end being applied to the offending fastener.

I purposefully leave the bolt head a tight fit and lightly tap (rough but effective) the ring spanner onto the alloy bolt. I apply force, but to no avail. Four feet of water pipe is slipped onto the spanner and further coercion applied. No go. I jump on the pipe. The bolt does not give but the force is sufficient to rock the bike off its centre stand. I barely catch Rhonda in time, muscles straining to the point of bursting and hernias imminent. I decide on a new tack, as they say in the Drowning For Pleasure Brigade.

The Stahlwille is removed and a hexagon impact socket fitted to the bolt head. Out with the trusty impact driver and the mighty two-pound engineering hammer. Two forceful blows and it has become blatantly obvious that the front end of the machine (wheel, forks etc) is hindering proper application of the knockometer. The front end’s due for new seals and an all round check-up anyhow so, off with the wheel, out with the fork tubes and it becomes immediately evident that I should have put the bike up on blocks before attempting this course of action.

After applying Dencorub to my arms and legs – strained from catching Rhonda one more time – I turn my attention back to the offending bolt, socket, impact driver and hammer. Several extremely forceful blows and nothing, it seems, is happening.

I decide to take some of the advice of my mechanical mentor, Mr Michael “The Cycle” Collins, one of Nature’s gentlemen and an absolute genius at practical, inventive mechanics. He often advised me with the following words: “Don’t force it, use a bigger hammer.”

Now, as strange as it may seem, there is much truth in what he says. It is much easier to impart force with a short, sharp blow from a very large hammer than it is to impart the same force with a mighty haymaker from a medium-sized hammer, and it’s also much more precise. This is the reason that hammers are made in a wide range of sizes. I reach for the three-pound block hammer.

A solid blow followed by another solid blow yields results: the impact driver self-destructs. Bits of spring, ratchet, handle and bit shower around the general vicinity nearly blinding Poor Me with shrapnel. I’m starting to become slightly annoyed.

Being in a hammer mood, I decide that perhaps, if I was to place one of my less essential ring spanners upon the bolt and then apply a little radial persuasion with the three-pound block hammer, some loosening of said bolt may well result.

On with spanner, down with hammer and, to my surprise, the ring of the spanner snaps and spins on the bolt head, once again removing all the points from same. I groan loudly and return to the toolbox, this time to choose an Implement of Destruction. The niceties of mechanics need not be observed further since the bolt head is now completely stuffed.

I consider, at this point, the use of violent brute force to be appropriate and select the large (genuine Petersen) Vice-Grips. Carefully adjusting said Vice-Grips I attach them to the almost deceased bolt head, once again raise the mighty block hammer and, after three blows, the Vice-Grips self destruct. The spring breaks and the tiny tab removes itself from the inside of the handle causing the Vice-Grips to fall from the bolt head … but not before chewing same to slag.

There seems to be no alternative. It’s time for the Big Guns. I repair (operative word) to the garage and return with my 24-inch Gedor Stillson wrench (a bargain – the first time I used it, it paid for itself). Carefully adjusting the killer wrench, I place it upon the bolt head. One, two, three, heave … and the head is sheared straight off the bolt by the hardened jaws of the Mighty Tool. I swear loud and long.

That’s it … no more Mr Nice Guy! I grab the Electric Speaking Trumpet and, as night begins to fall, call Mr Col “More Stuff” Grogan.

“G’day. Col here.”

“G’day … it’s Smith. Can I borrow that big, mean industrial angle grinder with the kryptonite cutting disc?”

“Sure. What do you need it for?”

“Clean a chook.” (There’s a story there which I’ll relate to you all soon.)

“Okay, see ya.”

A short trip to Davey Ireland’s place (‘struth, and can young Davey sing) secures the power tool in question and, in the backyard, by the light of the moon and a lead light, we’re ready to give ‘er heaps!

Lights! Power! Action!

The roar of the grinder fills my ears as I attack the remains of the bolt head with a vengeance, for I now hate that bolt with a consuming passion. Showers of blue sparks light the yard. A few of those glowing shards of metal find their way into the exhaust stubs, igniting the carbon deposits they find there and saving me the effort of a decoke.

After five minutes’ work the oil filter housing falls off. It’s all a bit of an anti-climax really … as a young girl once said to me.

The next day I venture to the wreckers (Moreparts in Georgetown, if you’re ever short of a bit in Newcastle, which is the story of my life), there to purchase, second hand, an oil filter housing and bolt/oil regulator for the princely sum of $10. Thus far the exercise has cost me $10 for the new (old) filter housing and bolt, $13 for a new set of Petersen Vice-Grips and $9 for a new impact driver. My peace of mind also copped a pasting, as did my poor, long-suffering knuckles. What went wrong?

It seems that, on inspection, the problem was caused by a number of contributory factors. Firstly, the bolt hadn’t been removed for the proverbial roo’s age, as was self-evident from a squiz at the oil filter element, causing the bolt head to corrode itself to the oil filter housing. Secondly, whomever (correct English, folks) had previously assembled the oil filter and housing had omitted a very important spacer.

It all added up to a swag of anger and aggravation for a certain Smith-like creature. I detest being forced to destroy a part in order to perform routine maintenance, and it all points to one reason why, sometimes, professional mechanics are forced to charge what seem to be rather steep prices.

If I’d been employed in a workshop, that little piece of travail would have entailed about three hours’ yakka at $20-$25 per hour plus parts. I often find I am deeply sympathetic with the small professional motorcycle mechanic, walking, as he does, the tight-rope of customer good will and a fair return for time spent. I’m glad I don’t fix things for a living any more.

Cop you later.

By Peter Smith. Two Wheels, February 1986

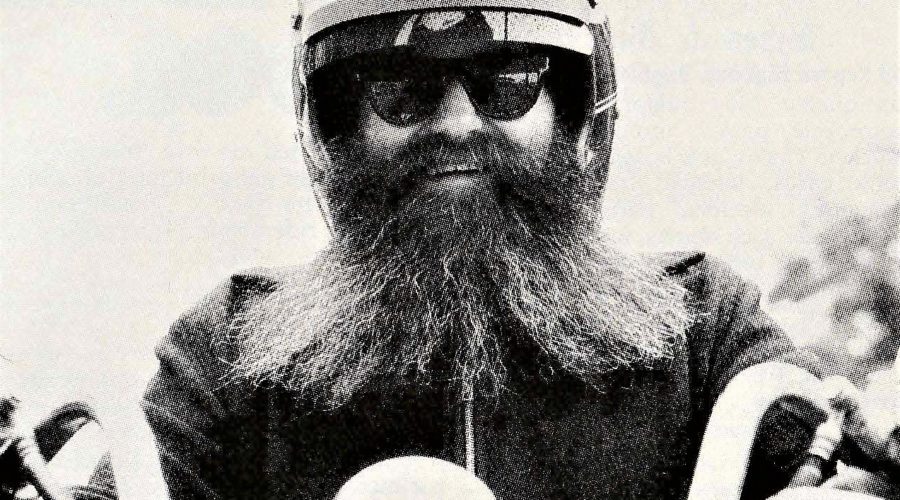

Peter Smith was a motorcyclist extraordinaire, a towering intellect, a bluesman of note, a lover of the grape and a wonderful raconteur, whose Mr Smith column, published in Two Wheels magazine from 1985 until his death in 2009, made him a much-loved and admired writer in the Australian motorcycling community.

Now, his early Two Wheels columns have been collected into a limited edition book: Mr Smith, A Sharp Mind in a Blunt Body. Featuring the complete collection of his Two Wheels columns from 1985-1988, plus some of his best feature stories and personal recollections from John Rooth, Geoff Seddon, Grant Roff and Guy “Guido” Allen, it’s a must for Mr Smith fans and a unique tribute to Australia’s greatest motorcycle writer.

Only 1000 copies have been printed and they are nearly all gone. Priced at $29.95, including postage, you can order a copy here. All profits go to the Black Dog Institute.