Kel Wearne

Kel Wearne, also known as Captain Flashbulb, was Australia’s answer to Hunter S Thompson, and throughout the 1970s and early 1980s was very prolific in Two Wheels, writing epic long distance road tests of big blasters, testing pointy end dirt bikes to the limit too as a highly accomplished off road racer, and penning his must read Behind Bars column each month.

Kel’s view of the world, and motorcycling, went way beyond anything that anyone else could possibly interpret or explain, so here is the man himself, in full flight, with a piece he wrote looking back on his Two Wheels days for the 35 Years of Two Wheels anniversary publication in 2003.

Kel Wearne died in 2017, aged 71.

I first saw Two Wheels in ’69 – in Papua New Guinea as a Patrol Officer and a long way from riders’ roads, although I still managed to have five bikes at Wewak, including a black Ducati 350 single with all black wiring – real smart – and clip-ons, that could be white knuckled around the only six kilometres of asphalt between the pub and the airport in-between village ‘trucks’ and native flora and fauna taking up the town ‘boulevard’ in those days.

It was when I was back in Ozland a couple of years later with a Norton Commando 750 Fastback, the first Honda CB750, a Yamaha R350, and a Husky 250MXer that TW became an intrinsic part of my life for the ’70s. A long way from the tropics in Melbourne.

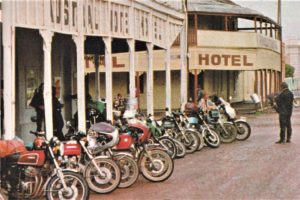

The Peter Stevens dynasty was just starting in Victoria, same with the legendary Castrol 6 Hour race in the coliseum at Amaroo Park, the Kew Boulevard was virgin for practice, there was the gigantic Hattah Desert Rally near Mildura, and everyone still knew what a ‘ton’ was. Saturday morning and you were embarrassed to be in a four-wheeler in the CBD of Elizabeth Street, Melbourne, where it was perhaps the most concentrated public bike show each week in Australia as ‘business as usual.’

Oh yeah, and there was no 100km/h nightmare to limit riders’ throttle hands on any highway. You could ride around Ozland and set a record with publicity in most motorcycle mags and even some sponsorship, without you and your family being expelled from the community. A racer friend and I were going to do it with Yamaha at the time of the release of their XS1100 but we, I, fell out over splitting the deal from Yamaha. The 100km/h limit came in the day I returned via the Newell Highway from Sydney to Melbourne on an ex-Castrol 6 Hour Laverda Jota 1000 – it started the necessity to develop psychic abilities while riding and/or have excellent mirrors and radar detectors. Either way it detracted from focusing on the ride.

Yet before then Australia seemed as good a place as any to be for a misfit from the jungles. I was a bored MX hopeful and writing for the Melbourne Age. TW editor Mac Douglas phoned me from Sydney in 1973 and the connection with TW began – a winter’s ride up the coast on black ice with road-racer Rod Tingate and the first ‘Open Road’ tests with the waterbottle Suzuki GT750 and 550, en-route back standing on the pillion pegs leaning over Rod down a long hill to get a photo of the speedo reading 170 klicks and my ears freezing after about three repeats (no helmet so I could focus).

These were the years when the Japanese were in the process of Sumo-body flattening the world and the Europeans hadn’t yet begun to realise they would have to go through their downs before regrouping: returning to show that copying and cloning with production line sophistication is not what every rider wants and thus we have the incredibly virile and diverse Europeans of today. But that is now — 25-30 years ago there was a lot of complacency.

It was the time when AMF owned Harley and you needed to be a mechanic, or have one as a mate, to get to ride those mid-’70s twins. Triumph and BSA had already tried their born-again moment with the triples, yet for Triumph it was a harbinger of what would be reincarnated as a great range some 20 years later, while the Laverda 1000s, Moto Morini V twin 350/500, Benelli 750/900 six, Ducati SS900 and co, showed the irrepressible style, flair and creative artistry of Italy, with Guzzi virtually a stand-alone icon of unchanging conservatism and still surviving – much as it is doing today, I guess.

The period would include copycat designs of each other, by the Japanese, some excessive engine designs to show manufacturing prowess – the six-cylinder Z1300 Kawasaki and Honda CBX/6, and the delightful Benelli 750/6, as well as the Honda four-cylinder 250. I rode them all but never tested the 250 as my ego at the time prohibited me being seen on anything smaller than a 500 (dirt bikes not included).

Although I did accept a bet and tested the Kwaka Z400 twin for ‘Open Road’ from Sydney to Melbourne in ’78, immediately after spending three months on two Honda six-cylinder CBX1000s. I used the Hume as the shortest way and the 22-wheeler ‘wind buffeting effect’ was incredible on the little bike. Yep, I don’t like little road bikes at all.

But it was the four-cylinder fours that dominated the ’70s, end of story. The Rising Sun Big Four each had them. What stands out – the Kawa 1000 then GPz900 and the Honda 900F although longevity probably goes to the XS11 Yamaha. In among that lot BMW introduced their 900 Boxer which showed long term model runs were okay against fashion. The sad part was the falling away of Laverda – the 1000 triple being one of my favourite bikes and having a place in my absolute hall of fame.

Yet, despite the range of multis and the silly game of turbocharged models, the fastest point to point bike I ever used in the ’70s was the Guzzi. Not the LeMans. The 850 T3 and T4 with 25-litre fuel tank and top end cruise speed of around 190km/h, with a rectangular spotlight, comfy seat and small screen, did more to make distance than any other bike I tried. And I sure tried.

But fuel consumption of the multis killed some runs – the grim ones being 6.8km/l (14.7l/100km) and 7.8km/l (12.8l/100km) which really indicated how hard one was trying. The first one caught me out on the CBX1000 in central NSW late one night.

The other four included the MV750 Agusta butterfly tank and the later SS750 America model which were amazing engineering pieces of history. I interviewed Mike Hailwood for TV at Amaroo Park and he did a few laps on the great red beast – commenting he wondered how he ever rode them so fast compared to the Honda. I think he could have ridden a brick fast. But the MV was a distinctly different personality to the fours from the Big Four.

So there I was refusing to move to Sydney and, at one stage, averaging some 4000km a week riding interstate, testing. It was no career move. It was no smart beans. It was purely some escapism.

Let us accept that this 3D realm we live in is a hologram – and science has proven that each cell in your body can be used to recreate you exactly – which is a DNA hologram, right? And the same science has proven that you and everything you think of as ‘reality’ are just a few sub-atomic particles spinning round in space, forming what we think is solid.

If we are just a hologram then we actually exist somewhere else – this ‘here’ is just an illusion. Knowing this I used momentum, speed, as my meditation technique – the faster-you-gothe-slower-it-seems realm – where you ride a slow dream of 4000 klicks a week, preferably at night, to escape the illusion. Along the way I realised it was no longer the Open Road test. It had become the ‘Interstate Express’ test – city to city – awake, asleep (you wake when your hands fall off the handlebars, or you wake being launched out of a run-off culvert at terminal velocity beside the highway…but these are other stories). It became a way of living, an obsession.

I like the night – I’ve done more than 60 per cent of my riding, since starting in 1960, at night – the elixir of night, speed, spotlight (used to fit one to many testbikes), is the most mesmerising, focused, yet free meditation imaginable – just the ‘lit-bit’ ahead and trying to average 160 is real focus.

It meant no pillions. It meant few companions ever repeated a ride. It was blasts around Victoria in mid-winter with the late Ken Blake and ‘AJ’ Andrew Johnston on turbo-charged GS1000s and XS1100s with the frames twisting like rubber bands.

So there I was doing all I could to find the Last Great Adventure and riding Melbourne to Sydney, M to the Gold Coast, M to SA, M to Broken Hill, etc, and I still couldn’t find Zen! Consciousness only came later with my Sufi Master in WA that, while I was trying to exit, it wouldn’t happen – like Dave Saunders (REVS contributor), Rosco at Bathurst, and another dozen I knew.

But the Universe did show me the Dharma, Karma, Moksha bit with multiple fractures of the spine, neck (coma), ankles, knee, shoulder and wrists from dirt bike racing. Nature’s way of telling me to reappraise my philosophy.

The TW stage of the ’70s was completed in the early ’80s – in 1982-1983, with the trip to Japan with Yamaha and to Italy. Italy was testing the 120-degree crank Laverda RGS1000 and Jota and riding at any speed one felt like at any time – awesome. It also finished my tyre knowledge by riding on the first radial ply tyres with Pirelli. I was so abstract at the time with the work in WA that I blew offers by Pirelli to work in PR in the USA and with Yamaha NVT at their headquarters in Amsterdam. I really know how to blow up bridges before I cross ‘em …

Yet everything is a circle in some way – the ‘70s were nearly all naked bikes – where the motor dominated the visuals. Technology was trying to catch up with power in tyres, suspension (rear especially) and frame design. It’s interesting that now, in 2003, the naked bikes are back in a big way and we still have many designs with the old ‘conventional’ twin rear spring/damper units. While I am conservative in liking unfaired bikes in general and big round headlights, I am definitely in favour of single shock rising rate suspension over the twin shocker designs. Much easier on broken spines.

So the ’70s, the era of the superbikes, warts and all, were a long way from the Timewarp models of today. Yet the genesis was in this hectic epoch, where archetypes ruled. The mutha fours dominated but the Dukes and the Beemers kept the loyalists content. Cruisers were still USA apart from Goldwing buyers. The purists had the custom frames to choose from, amongst these were the Egli, Rickman, Harris and Moto Martin. Just add a Jap four. I owned a Rickman Kawa Z1000 and later a Moto Martin with much modified ‘1400’ Kwaka engine. The later pushed 300 kays but that too is another story.

My favourites depended on moods but in general were for long distance. My personal choices from the ’70s include the Laverda Jota 1000, Guzzi T4 with Le Mans bits and suspension improvements, BMW R90S, and either the Kawasaki Z1000 or the Honda 900F2 along with the Harris frame for the latter two engines, or the GSX1100 engine.

If I was choosing just one now in 2003, stood the dance of the time weaver, I’d go the modified Guzzi. If Laverda was still going strong, I was feelin’ strong on the day, and my knee wasn’t Teflon and stainless, it’d be the top-heavy Jota.

And the fundamental difference between the Kel and the Sydney TW and REVS crowd of those days? Living archetypally – living the dream of the T. E. Lawrences of the world. It was never a job and I never looked at any future. Yet here I am back on the east coast wondering where so many people have gone and who is still living their dream?

Motorcycles are not the end, they are the means – the gateway, the portal, the back to the future, the Stargate – which is always towards yourself.

At its highest level the bike is the Piper at the Gates of Dawn. Riding at this level is the vortex of your creative experience and fantasy, combined with Taoist meditation-in-movement. I think this is not clearly recognised in most motorcycle magazines today – it’s all too clinical, mechanical. I think the ’70s was the last period when TW, the Bike Book, Cycle World USA and others ran fictional pieces, philosophies, alternative expressions of the Dream.

TW gave me the location to anchor and express my dream. And I’m glad I was part of that period.

By Kel Wearne. 35 Years of Two Wheels, 2003.