1970 Honda CB750 Four

To nobody’s great surprise, we found the Honda CB750 the most impressive motorcycle we’ve ridden. It wasn’t what we expected, but it was a very exciting machine in all respects.

We laughed when Bennett Honda told us they didn’t want any high-speed work done on their Honda Four — laughed long and loud.

We went out to pick up the big brute to do our road test, in full expectations of being mounted for a few days on one of the grooviest sports machines to hit the market here in a while.

Naturally, on a sports machine, you can go hard and press on a bit, weather, road surfaces and you know whats permitting.

So when they told us to take it easy on standing quarters, acceleration and top-speed runs, we thought, “You gotta be putting us on, man!”

And that was mistake number one.

We expected a sports machine but (and I fully expect to be shot down in flames by a million readers for this remark) the Honda Four is not a sport bike – it’s a touring machine.

Nor, in direct contrast with most of its brothers, sisters, cousins, aunties and uncles in the Japanese motorcycle glut currently upon us is it an ideal around-town-and-suburbs runner.

The Honda Four is happiest, and most enjoyable to ride, on the open country highway, completely deserted by other traffic, copless and free.

Only here can the big 750 cc four-banger be made to sing as it was meant to do, and as it loves to do.

A glance at Honda’s glorious full-colour brochure on the big bastard would be enough to convince anybody that here is an all-round stormer of the first order: a killer at the lights, and just the thing for showing that mug in the Monaro that he can’t push you around, a sure-fire winner at every club sprint.

And of course, all these things are well within the Four’s capabilities. But they’re not what it was built for.

One gets the idea, somehow, that it was basically intended for high-speed cruising over large distances on glassy-smooth American freeways. It gives the impression of being almost the ultimate example of American requirements and their influence on the Japanese motorcycle manufacturers.

This is not so say, by any means, that the Four is not suitable for Australian conditions. It most certainly is.

For the long distances most Australians cover from time to time, the effortless maintenance of high speeds mile after sweeping mile is a true delight.

One of my most enjoyable moments with the Four was on a stretch of road that many of you may know. It’s the back road that winds down from Terrey Hills to Bayview through Kuring-Gai Chase north of Sydney, past the turn-off to West Head.

Punting the Honda down through tight and not so tight curves, some beautifully cambered, some diabolical, up and downhill, hairpins and all, the overall sensation was one of sweeping along, rather than winding. The only conscious effort required was that of selecting the right speed for a given corner. After that the bike itself seemed to pick the angle to heel over to and the line to take through the corner.

I felt like the original Assyrian sweeping down “like a wolf on the fold”, if you’ll pardon my plagiarism.

On more open country highway, like the SydneyNewcastle Expressway, which to my mind is the epitome of open road, the Honda Four really came into its own. It more or less took over.

From the tollgate, it was simply a matter of working it up to top gear and settling back to enjoy the run, with no anxious moments (apart from half-witted four-wheelers and envious truckies), no sweat, just the song (and indeed such it is) of the big mill at its best.

If I am making the Honda Four sound like a bike with but a single purpose, let me hasten to correct that impression.

It is an all-rounder that just seems to shine particularly in touring.

Sure, it accelerates: I mean, standing quarters in 12.3 seconds (incidentally, the manufacturer only claims 12.6) are not to be sneezed at, nor is a speed of 106 mph at the end of that quarter.

If your sole aim in life is hosing off everything in sight at the lights, I pity you, but the Honda Four will do it — although you probably won’t live to enjoy your triumph with that sort of riding.

If you like slipstreaming Copper…sorry, Cooper S’s and then blasting past them up a 10 degree hill, here’s the machine that’ll do it. Just tell your story to the magistrate.

From my own point of view, as a reasonably sane sort of motorcyclist, the joy of the Honda Four’s 67-odd horsepower is not doing these things, but the inner satisfaction of knowing that I could if I were stupid enough.

On a more practical note, there’s the safe feeling of knowing that there is ample power on tap to get you out of most tight spots, even when there are two lives to be saved. That special chick on the back may not appreciate it, because you probably won’t tell her how close it was.

My acquaintance with the Honda Four began, as do all our road tests, in picking up the bike from Bennett-Honda at Mascot and pedalling back to the office through chock-a-block inner-suburban and city traffic.

In this sort of going, the Honda’s 481 lb gassed-up kerb weight becomes tiringly apparent. You don’t nip in and out of the traffic. You haul yourself and the bike through the gaps with considerable effort.

And that, of course, is just my verbose way of saying that I found the Four a trifle heavy for dense traffic zipping.

When the gap opens, though, you can be sure you’ll have the steam to take advantage of it.

The overall heavy feeling down low is exaggerated by the solid, he-man controls. The clutch needs to be reefed in, the gear lever has to be firmly and positively booted into place, the brake pedal needs to be shown who’s boss, and the hand-brake action is not light either.

On the subject of the hand brake, we come upon one of the bike’s more unusual features (apart from the engine). The brake handle operates a hydraulic disc brake on the front wheel.

Imagine the big brute again in its natural habitat: the open road. You come smouldering over the brow of the hill, only to find the way down the other side blocked by a semi-trailer or a Mini towing a 36 cwt caravan. With 80-something on the speedo, you pack death: a gentle, even progressive tightening grip on that ball-ended lever, and you’re toddling along at 25 mph behind the blockage, until the next stretch of open road where you can safely get around.

We didn’t have an opportunity to put it to the test, but the manufacturer claims a braking distance of 36 ft at 31 mph, and I for one am quite prepared to accept that as being possibly even a little on the pessimistic side.

The disc itself is an 11.7 in. unit, operated from a master cylinder mounted on the handlebar, just near the lever.

You may note that in our photographs the disc seems to be more than somewhat scored. Running the finger over the disc reveals that the metal is not in fact unduly scored, but rather just stripped, for some reason. There is little or no grooving, and what there is is purely the result of over-enthusiastic testers getting carried away with disc brakes and trying to stand the bike on its nose on dirt.

The bike’s other unusual feature is, of course, the engine. Four cylinders in line across the frame, overhead cams, aluminium alloy, air cooled, four stroke, and almost obscenely efficient.

Capacity is actually 736 cc (or 44.9 ci), the result of bore and stroke of 61 mm x 63 mm (or 2.4 in. x 2.48 in.).

Compression ratio, at 9:1, is just about perfect for the octane rating of any super grade petrol available in Australia, but still makes for nice, easy starting. None of this absurd jumping·from great heights as required with other 750s, just a positive flick of the knee and ankle joints.

But of course, you don’t even have to do that. It’s also got an electric starter with a button where it ought to be. On the handlebars.

Of the engine’s other features, probably the four 28 mm (Keihin, of course), piston-valve double-float carbies and the beautifully-designed and superbly efficient exhaust system are most worthy of mention.

As the world’s only four-cylinder mass-produced street bike, the fact that it has come from Honda is hardly a surprise, in view of Ichi-Ban’s (Number One’s) continued leadership in its field. Think about that. Look at some of Honda’s racing machinery, as far back as 10 years ago.

As far as the way the engine works, I don’t think I can improve on the essence of Honda’s own description: Smooth, effortless power all the way.

Although the engine peaks out and is redlined at 8.5-9.5 grand on the tacho, it reaches peak power output of around 67 horses at eight grand, and top torque of 44 ft/lb comes on at just seven grand.

This is not to say the engine has a narrow power band. Quite the contrary. It will pull away from low speeds in top gear without any fuss or fury, smoothly and without apparently straining itself.

For those of you more interested in technical specifics in the guts of the mill, the two outer and two inner cylinders fire at 180 degree intervals. Offset valves are fitted in the hemispherical heads to permit big valves to be used for better breathing.

Both the overhead cam and primary drive are taken from the centre of the one-piece crankshaft by automatically-tensioned chains.

Lubrication is high pressure dry sump, keeping the innards cool and slippery, and working through a dual trochoid 57 psi pump from a three-quart sump.

The gearbox has five speed, constant mesh, with ratios of 2.5 for 1st gear, 1.708 for second, 1.333 for third, 1.097 for fourth and 0.939 for top.

Primary reduction ratio is 1.708, secondary is 1.167 and final reduction rate is 2.812.

Keeping changes crunchless is a wet seven friction disc 5.5 in. clutch.

Electrics are 12-volt (and let’s face it, with electric start and a 50/40 watt headlight they’d have to be).

The frame, like so many other aspects of the machine, is a thing of beauty, with tubular double cradle structure for lightness and strength.

Suspension involves hydraulic tele forks at the front and swinging arm at the back, damped by compression gas units on the rear, while the lower legs of the front forks are alloy.

Physically, the Honda Four is a big bike, standing 44 in. high, 85 in. long and 35 in. wide, with a 57.3 in. wheelbase, 6.3 in. of clearance and seat 31 in. off the deck.

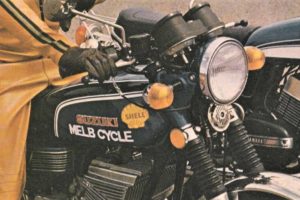

You’ve seen the bike, so you can judge its looks for yourself. I personally like the style. I think it looks great.

To ride, it’s beaut, provided you’re firm and positive with the controls. You can’t pussyfoot with this one. You’ve got to show it you’re in charge at all times.

The controls are conventional and well-placed, and the only thing on the Four that’s not on your average set of handlebars is the hydraulic fluid reservoir and master cylinder (one unit) mentioned before.

Lights are excellent, although I don’t think I’d risk 125 mph at night even with the wide spread of the bike’s high beam.

Instruments are beautifully placed, angled for easy reading, white on black and well lit at night, with a 160 mph speedo and an 11-grand tacho with the red sector between 8.5 and 9.5 grand.

Fuel consumption on our test worked out to around 55 mpg at an average of about 50 mph, so it’s probably not the most economical two-wheeler in the market place, but you’ve got to sacrifice something to get that power.

The brakes refused bluntly, in spite of my best efforts, to fade or shudder.

Oh, nearly forgot. There’s another feature about the controls I specially liked, and it’s almost a must with a bike as big and powerful as this one.

It’s got a chicken-switch, panic button, or kill button, whichever you prefer. I’m glad I didn’t have to use it, but it’s comforting to know it’s there.

Styling is sleek and looks powerful, with candyapple paintwork and gold striping, chrome everywhere, quilted seat and sporty quick-flip filler cap.

I don’t know – maybe I’m prejudiced because I like power, performance, styling and safety – but I found the Honda Four tremendously exciting. I loved it, and damn near broke down and wept when I had to give it back.

It’s got pose value, and the guts to back up the pose.

It’s got “go” and the wherewithal to stop the “go”, as well as the handling and balance to put it to good use.

The 3.9 gallon tank with 1.1 gallons in reserve, at around 55 mpg, gives it a reasonable but not staggering cruising range; but then again, pulling into a service station to gas up is a pleasure if you’re anything like the unashamed poseur that I am.

Hats off to the Honda CB750. It’s a bottler.

In a single word, exciting.

By Derek Pickard. Two Wheels, April 1970

Guido from AllMoto owns a 1971 K1 Honda Four. Fancy parking what’s arguably the most significant motorcycle in history in your shed? Read his assessment here.