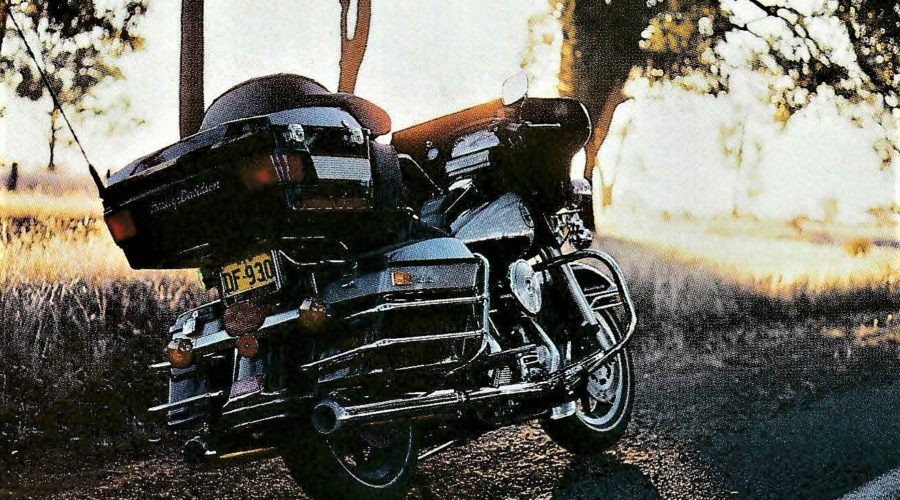

1989 Harley-Davidson Electra Glide Ultra Classic

Is the Harley Ultra Classic Electra Glide the ultimate tourer or just an undernourished road train? Roothy had plenty of time to relax, do silly things and ponder the answer.

Warren Fraser looked at me as if I’d just asked for a loan of his wife.

“The Ultra Classic? You want to borrow my Ultra Classic?”

Fortunately I’d been warned to expect this. Apparently, ever since the FLHTU Electra Glide Ultra Classic had been registered for demonstration purposes, boss-man Fraser’s butt had been welded to the seat.

So what is it about the Ultra Classic that gets such a response from a man who has been around motorcycles all his life. In a word, it is Ultra. It’s as impressive in the flesh as anything on wheels and great fun to ride. After all, how many motorcycles have an integral stereo, super comfortable seats, footboards, CB radio, cruise control, cigarette lighter – the list of features oes on and on.

OK. I know what you’re thinking. It’s a great big chunk of junk, right? Not a real motorcycle at all – more like a twowheeled garbage truck. Real bikes have got an engine and wheels and precious little else blah blah blah . . .

Well, I doubt there’s anything I can write that’ll change your opinion and I’ve got to admit to having echoed those same sentiments myself more than once in the past. The trouble is, and this is something Fraser knew all along, it’s impossible to trot off something like 5000 kilometres on a bike like this and not suffer a change of heart. The Ultra Classic is a true distance machine and what it does well, it does very well indeed.

As to how it does it, the motor is Harley’s 1340 cc Evolution – little changed from previous models except for the addition of a plate between the carburettor and manifold to restrict things down for those good old ADR compliance.

Other than that, the power train is typical of all the late model Evolutions with the exception of the Springers, Softails and Heritages in that it employs a rubber mounted motor and gearbox as well as the five speed gearbox and belt drive. Even the gearing is the same, which makes it absolutely ideal for touring with fourth gear virtually the same as the old four speed Harleys (3000 rpm equals 100 km/h) and fifth gear now an effective overdrive, dropping the engine revs by 500 rpm at that same 100 km/h.

Perfect match

If ever a motor suited touring use, it’s the 1340 cc V-twin. Big, fat, relaxed power, delivered with a rolling cadence that has a lot in common with a horse at full gallop. With all the gear plus rider, all-up weight on this trip would have been over the 450 kg mark easily, yet the Evolution donk refused to be over worked. It doesn’t strain, even though its performance in real terms of acceleration and top speed is very much on the lazy side. Even under full throttle, something that’s hard to avoid when you’re in a hurry, the Ultra Classic responds as if there’s tons of poke in reserve – it’s just you’re not getting any of it.

That’s got quite a bit to do with the previously mentioned restrictor plate and the ultra quiet mufflers – Harleys need to breathe – but it’s also quite in character for the bike itself. Riding around town had me noticing the lack of performance and thinking that life on the highway was going to be an ADR inspired bore.

It wasn’t to be at all. Once all that momentum has been stirred into life, the thing’s a sheer joy to pilot down the road. Naturally enough, 100 km/h cruising is an absolute bludge with all the time in the world to relax and have a good look around, but when the road straightens out – like the Hay Plains for example – it’s amazing how easily a good speed can be maintained. With the speedo nudging 140 km/h and the cruise control switched on, that’s where you stay for mile after relaxed mile. A stiff headwind or a good hill will knock it back some 20 km/h or more and unlike most Harleys you’re often looking for fourth gear when there’s some serious passing to be done, but even then with 5000 rpm equalling 140 km/h in fourth, it’s still very much relax city for the rider.

Ah, cruise control, something I’d figured was a real piece of tinsel on a motorcycle. The trouble is, you use it because it’s there and before you know it you’re using it all the time. It’s relaxed and right in keeping with the rest of the bike.

The Ultra Classic’s cruise control is a far cry from the traditional Harley throttle lock screw. Once the master switch on the inside lower leg of the fairing has been switched on, there’s a small button on the right hand side control block which the rider touches to program in the engine’s speed. The cruise control then takes over operation of the throttle to maintain that speed. This translates to a sort of fixed logic for the bike as you can feel the throttle opening up when you hit a hill and closing down as you glide over the crest. Use it at much less than 70 km/h and the ride is jerky as the carburettor opens and closes too quickly for the motor’s workload to even out. Much over 140 km/h and it’s as if some instinct for self preservation takes over and the bike consistently drops back to maintain 135 km/h. But between 70 and 135 km/h, the system is flawless in maintaining road speed and that’s right where you need it for touring.

Chugging

When the Ultra Classic is pointed up a long hill with cruise control switched on, it will labour away trying to hold the speed until engine revs drop to the point where a gear change is called for. At that stage it automatically cuts out, refusing to work the motor on low revs and full throttle. The only thing missing here is a little buzzer to wake up the rider …

Touching either of the brakes immediately cancels out the cruise control as does rolling back the throttle to the stop, but it can be manually overridden if you need a bit of extra speed for passing and will then settle back down to the pre-set speed. Changing speed settings is as easy as touching the brakes to cancel, getting the road speed to where you want it and then touching the set button again. A simple little thing, but the only time I had that master switch turned off was within big city limits. You can get addicted to something that takes the effort out of distance work, it’s that useful.

Takes the effort out of distance work – somehow that cruise control sums up the whole motorcycle. From the minute you lower your bum into the plushly-shaped saddle the whole plot spells comfort to the max. A rider’s eye view takes in the wide and tall handlebar mounted fairing with its full complement of instruments – speedo, tacho, oil pressure gauge, voltmeter – plus the stereo/radio cassette unit, speakers and cigarette lighter.

Looking down allows you to check out the running boards with their sprung footpads – no tingles and lots of room to shift your feet around on the run – as well as the rocker gearchange unit and the hefty footbrake pedal that’d shame most cars. The ‘bars fall easily to hand and rubber mounting means there’s no hint of vibration here either.

Lard arse, good buddy

In fact, with everything being isolated by rubber, the only part of a rider coming into contact with solid motorcycle is his knees, on either side of the three and a half gallon tank. In the middle of the tank is the most accurate petrol gauge I’ve ever experienced and the controls for the 40 channel CB radio.

The CB mike which usually plugs into the side of the tank console was missing so I didn’t get a chance to add my bit to the airwaves. Probably a good thing really, as a few pensive sessions of listening to what the ten-four freaks were on about proved to be about as exciting as an ABC gardening show. However, before you write the unit off as a complete waste of space, consider the advantages in the event of a flat tyre or breakdown. It should be possible to find a motorcycle sympathetic truckie to either bail you out or give you a lift into the next town. Suddenly it starts to make sense.

We took an in depth look at the Harley-Davidson stereo unit when Bill McKinnon tested the Electra Glide (TW, April ’87) and basically the unit remains unchanged. With self-adjusting volume control and 80 watts of blast, it remains simply the best sound system ever fitted to a motorcycle. Whatever the speed or conditions, it’s always easy to hear what’s going on and channel search means your hands don’t need to leave the bars. Another feature of the Ultra Classic is rear speakers for the pillion complete with volume and tuning controls. Too much? Try telling a bored passenger that.

It’s one hell of an impressive motorcycle to look at. From the chrome guard rails on the front mudguard to the wrap around rails on the pannier boxes, there’s a consistency in the Ultra Classic’s gaudiness that’s appealing in its own way. Big, solid crashbars, the upright screen and full width top-box combine with the deep two tone paint work to create an image of sheer bulk.

It isn’t missed by non-motorcyclists. From the old bushie at Balranald to the yuppy couple at Apollo Bay, the comments were much the same: “Wow” followed by “How much?” A lady at the Salt Creek garage, south of Adelaide, said the Ultra reminded her of half a car. That could’ve been an insult, except she’d just stepped out of a pristine early ‘Fifties Buick. Like the Ultra, that lady had class.

I didn’t – not on that stretch down to Mount Gambier. With a good 3000 km clocked up since leaving Sydney I was used to the creature comforts of the bike and abusing the privilege. Normal practice – for me anyway – when out touring is to make most fuel stops a chance to stretch legs, grab a cigarette, a snack and a drink. On the Ultra, most of these things can be done on the run and leg stretching, arm bending and bum flexing aren’t necessary anyway. A smoke meant slowing down to 100 km/h, hitting the cruise control and punching the lighter. Who needs to stop?

Who’s a mug?

But I came unstuck after that Salt Creek fuel stop. I’d bought a can of Coke and a bag of corn chips and stashed them down my jacket. About thirty kilometres afterwards, the road looked like staying straightish for a while so it was time to pop the Coke. Sure enough, it was all fizzed up from being shaken around and the fountain that ensued liberally coated me and everything inside the fairing with black death – sweet and sticky. Then I missed with some of the chips and they swirled around in the vortex created behind the screen. Believe me, tarred and feathered ain’t so bad compared to being Coked and chipped. A man feels like a mug at the next fuel stop . . .

You get smarter though. The whole trick to travelling long distances on the Ultra Classic is that you don’t need to stop for anything except fuel. Sure you could travel from A to B on a faster motorcycle, but the Ultra is so comfortable and easy to ride it’s possible to put in any number of hours in that saddle and still be enjoying the ride. In the right hands, the big Harley is a mile eater extraordinaire.

Easy to ride? Well, first impressions are of the sheer bulk of the unit and wheeling the bike into a tight garage or backyard could have Arnold Schwarzenegger reaching for his truss. But once you’ve got over that ‘if this stand breaks I’ll loose my leg’ phobia, and got the wheels turning under their own power it’s really a piece of cake.

With a rake and trail of 26 degrees and 157 mm, matching fat 16-inch wheels back and front plus the natural balance of a heavy motor low in the frame and a seat height of only 711 mm, low speed steering is excellent. It takes a bit of confidence to haul the motorcycle around a carpark or thread through a busy garage but it’s a damned sight more manoeuvrable than most sport bikes once you’ve had some practice. It’s easy to see why Harley dressers have been the chosen mount for all those generations of American precision and trick riding teams. Another seven guys hanging off the bike isn’t likely to affect stability that much …

The steering remains light right through to top speed – an indicated 170 km/h achieved on a downhill stretch of the Hume Highway with a bit of a tailwind. In restricted form, that’s all you get but it’s enough because the handlebar mounted fairing creates a gentle weave felt from about 140 km/h plus anyway. It’s not dangerous and, as much as anything, what you feel is a product of all that weight mounted on the ‘bars, which is more likely to accentuate any oscillations rather than dampen them.

And even when you take the machine to its limits, it still tracks straight and true despite the undulations of the ‘bars. When you’ve got that sort of weight travelling in a straight line at speed, momentum gives you all the security you need.

Pumping Iron

Holding up that weight is air-adjustable suspension front and rear. With the aid of a small pump and gauge it’s easy to adjust and the range can be controlled from soggy soft through to way too hard. After some experimenting I opted for 15 psi up front and 20 psi at the rear. Travelling solo, albeit with a fair amount of clobber (ever noticed that what you need to take on a trip varies directly with how much the bike’ll carry?) this combination gave a reasonable compromise between comfort and sacrificing too much ground clearance.

The rear units needed a top up of some five psi every 2000 kilometres but the front remained consistent. Pumping up the front directly affects the anti-dive. Use much more than 20 psi and the front end feels almost solid every time you hit the brakes.

Twin discs at the front mean the Ultra Classic can really be hauled down but at the expense of a fair amount of lever pressure. It’s very predictable under brakes, no doubt thanks to all that weight hovering over the front wheel. The rear disc has more than its share of feel and you’ve really got to tromp on the pedal to lock it up. Used together, braking is consistent and sure.

The big surprise is just how fast the Ultra Classic can be made to go through the twisties before it starts to feel dangerous. The brakes come in for a good workout, although it’s nothing they can’t handle and the old left foot works merrily away on the rocker gearchange with fourth being the between corners gear and second and third shooting you through.

The Ultra -Classic steers from the hip, just like the other Harleys, although butt swinging is out of the question because the seat tends to position your backside pretty firmly. It’s a funny sensation – nipping through a few corners – because all that rubber mounting and plusho seat makes you feel really removed from what’s going on. And everything happens so slowly, thanks to a deliberateness of movement inevitable when so much weight is hanging course.

However, somewhere south of Melbourne lives a very embarrased Bol d’Or rider – proof that a dresser scraping its skirts through a tight section isn’t to be laughed at. Not when there’s a maniac onboard and he’s got AC/DC pumping on the stereo.

No amount of accessories can compensate for poor basic equipment, but the Ultra Classic shines through in this department too. The rocker gearchange allows for positive if a bit slow gear shifting, with the heel and toe method only of much use on the highway when things are a bit more leisurely. Around town, I found I was using just the toe in conventional mode and matching engine revs to wheel speed to achieve the slickest changes. The clutch, which has got a mammoth job to do, is actually quite light with a very progressive take-up. With the new lower final drive ratio, the five speed box has a gear for every situation except fast takeoffs, but the leisurely top gear makes it all worthwhile – 3000 rpm at 140 km/h is lazy motoring in the extreme.

Overall layout of the instruments and controls is very rider friendly with everything being easy to see and get to. With the feeling of isolation engendered by all the fibreglass, it’s a good thing that the rider is kept in touch with his steed by an oil pressure gauge and a voltmeter. Cold idle saw the oil pressure needle hovering around 15 psi which would then drop to 10 psi when the motor had warmed up. Cruising speed meant a reading of 15 psi regardless of weather conditions or how hard the bike was being pushed. The voltmeter recorded a constant 14 volts above idle, although lights-on dropped this by half a volt. Having pushed an Electra Glide several miles after running out of fuel near Molong some years back, I’m pleased to say that the fuel gauge on the Ultra Classic is super reliable.

Short hops

It needs to be. Effective cruising range under average conditions is only some 200 km, and that takes a dive when you’re bowling along above the speed limit and fighting a headwind. My average on-tour fuel consumption was around 11.5 km/l, but one rapid stretch of the Hume saw that drop to 8.5 km/l.

Previous experience with ‘off road use only’ Harleys – i.e. those without full ADR compliance equipment – has me thinking that these sort of heavy handed figures could be dramatically improved, but what sort of government would be anxious to conserve fuel? Especially when they make so much money out of taxing the bloody stuff.

Very little of which they spend on road works, so it’s some consolation that the Ultra Classic is very stable on dirt roads (I can hear you cringing Warren … ), the only problem being that if it does get out of shape, no amount of footing the ground is going to save the day. It’s either feet up and power on, or jump off and watch.

When darkness falls, the Ultra Classic lights up like the Queen Mary leaving harbour. Up front illumination is handled by an excellent headlight and two driving lights, the combination of which on high beam is enough to send a truckie scurrying back to Repco for another box of halogens. It’s a broad spread of light and more than ample for Harley-style cruising. At the rear there’s an impressive triangle formation formed by the taillight and two more in each side of the topbox. Visibility from behind is virtually Volvo proof – it’s that good!

The indicators front and back are large and bright, leaving little doubt about what the rider’s intentions are. All the FL series (touring machines) have a new indicator switching mechanism that is superior to the old block on-or-off system. There’s still a button on each side, but now hitting one button after the other means the lights flash from one side to the other, rather than shutting down the whole shebang like the other Harleys. There’s also a microprocessor self-canceller operated by speed and distance. All in all the indicators are a dramatic improvement over previous Harleys.

Even dyed in the wool fans of centrestands (like me) would have to admit that such a device would be wasted on the Ultra Classic. Who’s going to lift it? The sidestand is Harley s traditional long-throw leg which locks into place. Make sure the ground is level and hard and everything’s alright – although I’m sure I heard it groan a couple of times …

I didn’t though. Not once in some 5000 kilometres of touring, be it the drizzle along Victoria’s coast, the heat of South Australia’s sheep country or the boredom of NSW’s section of the Hume Highway at night with only speeding trucks to challenge for a piece of road. Eight days away and six of them spent in the saddle – if time and money were no problems, this is one ride that could have gone on infinitum. The Ultra Classic didn’t use any oil, there was no noticeable change in the rear belt tension and the rear tyre – newly fitted when the bike was picked up – looked like it’d be good for another 5000 km.

The fairing and seat kept me comfortable, the stereo kept me entertained and cruise control made maintaining good average speeds a breeze. In all the miles we shared, there was only one ‘breakdown’. A serious pothole shook the cigarette lighter loose from its socket and it disappeared past my knee.

But what price comfort? At over $18,000 on the road the Ultra Classic is an expensive machine until you put it into perspective. Our long term FXRS Sport, kitted out with a handful of extras, is worth a touch over $15,000. For another $3000 plus, the Ultra Classic is actually bargain buying when you consider the amount of extra ancillary equipment you’re getting for the money.

It won’t be every motorcyclist’s cup of tea, but for the serious open road enthusiast with the money to spend there’s quite frankly no better machine for the job. Harley-Davidson’s Ultra Classic has set a new benchmark in touring comfort.

POSTSCRIPT

IT was early Monday morning – about 1.30 am to be precise. I was almost home after eight days on the road and even though it had been a quick and relaxed trip up from Melbourne the prospect of facing the office in just a few hours time after so long on the road wasn’t exactly pleasant.

There’d been spats of rain throughout the afternoon and night and it looked like I was in for more before making it home. Somewhere near Enfield it started raining in earnest but with home less than half an hour away who cared?

I didn’t see the diesel slick spread across an already slippery section of three lane highway. It was a gentle corner and having just passed a couple of hidden patrol cars, my speed was down near the legal limit. One quick tank slapper and then the back wheel was gone with all the grace of a sinking battleship. I’d like to say I ‘threw it away’ but that’d be bullshit. When the crashbars touched ground I’d already fallen on my butt.

One thing about slippery roads late at night, there’s no friction to slow you down and no traffic to run you over. As my bum and elbows took the big slide, some automatic reaction had me looking up at the bike. It was an impressive sight – $18,000 worth of chrome and steel graunching its way down the road. I remember thinking ‘no worries, all the damage is going to be on one side’ just seconds before the Ultra Classic hit the gutter, flipped over and proceeded to wreck the other side.

Because no-one else was involved, there was no serious personal injury and no damage to property, the police who’d been so evident just a short while before weren’t even willing to come to the scene. I straightened out the right hand side crashbar – which was propping against the rear brake pedal and locking things up – and got the guy at the all night servo to give me a hand lifting the bike back on to the stand.

Except for the crashbar, all the damage was cosmetic – not cheap, but not enough to keep the bike off the road. I was pissed off to say the least. For eight days I’d babied that bike – no ocky strap marks, no stone chips, no rips in the upholstery – only a lost cigarette lighter to show for the trip and now one patch of diesel on one unavoidable stretch of slippery road had done all that damage.

I settled my nerves with a cup of lowgrade servo coffee and a cigarette. Walking back to the scene of the crime I spotted something on the road. It was that lost cigarette lighter. Somehow it must have lodged in behind the motor and it had taken a serious dumping to shake it loose.

“Oh good,” I remember thinking. “Won’t Warren Fraser be pleased that I didn’t lose that bloody lighter?”

By John Rooth, Two Wheels, June 1989