Ducati 1972 750GT and 1974 750 Super Sport

To mark the 50th Anniversary of the release of Ducati’s first production V-twin, the 750GT in 1971, Classic Two Wheels here presents Two Wheels magazine’s original road test of the model, plus an exclusive, original test of the most desirable Ducati of all, the legendary 1974 750 Super Sport, known as the “Green Frame.” We also take a close look at one of the bikes that put Ducati on the performance map, Bruno Spaggiari’s 750 racer that took second place at the Imola 200 in 1972, behind the winning machine of Paul Smart, who is sadly no longer with us following his death in October this year. And to wrap up our coverage of Ducati’s 50th, the world’s foremost authority on the marque, Ian Falloon, takes us back to the beginning, when Dr. Fabio Taglioni, the Michelangelo of motorcycling, created his masterpiece.

Ducati 1972 750GT

Take a 65-horse competition designed ohc V-twin, put it through a close ratio five-speed box, mount it in a totally rigid frame, hang the finest Italian suspension on both ends, limit the weight to 400 pounds, and you’re close to the latest and greatest superbly distinctive Ducati 750.

Italy’s offering to the superbike race was not designed to be toured with panniers or worn out in city traffic. It is a sportster of the first order, even the flashers and pillion footrests look out of place.

The most virile-looking road iron around is finished with a traditional black frame, polished stainless steel and alloy, and eye-catching metalflake yellow fibreglass tank and side panels. Instead of mounting the V-twin engine conventionally, the leading cylinder is tipped forward to the nearhorizontal to aid air cooling. The arrangement looks really different and is functionally attractive.

The front forks’ robust light alloy castings are a very stylish and business-like front suspension. The large angle of fork rake clears the front wheel from the leading cylinder head by nearly five inches, which makes the whole bike appear long, low, narrow and very, very racy.

Our test model was lent to us by Ron Angel who sells every shipment of these bikes long before they are landed. He kept one from the first lot, registered it and gave it to Ken Blake to run-in for production racing. Ken is shown on the cover when he was assisting us on one of the better parts of the test, at the Calder Raceway in Melbourne.

The only non-standard fittings on the Ducati were the flat bars, wired nuts to racing regulations and the omission of a rear view mirror.

The manufacturer’s first publicity, before their latest creation went into production, claimed 74 bhp from a prototype equipped with twin front and single rear discs. Although the only visible differences between that version and the current production bike are the use of only one front disc and a conventional rear drum brake, the engine has undergone a careful detuning.

Compression ratio has been lowered to only 8.6:1 (about the lowest “real” compression of any 750), the large Dell’Orto carbs have been changed for 30 mm Amal Concentrics and the valve timing is far more civilised. This results in a drop in maximum power to 65 bhp but a tremendous gain in flexibility.

Due to the detuning, the horny looking motor is incredibly easy to swing over and start. The kickstart lever does not require maximum effort, just bringing it up to compression and using the rider’s weight to ease it over. In more than 800 miles of all types of riding, starting never went past second attempt.

Mechanical balance of the layout is excellent and permits a tickover of only 500 rpm. Vibration never gets past the slight case of the tingles even when the motor is being revved out to 8000 rpm.

Naturally enough three shafts, five bevel drives, two overhead cams, four large clearance rockers and straight-cut primary gears put out a fair amount of mechanical noise. From a distinctive “clanking” at tickover to a low pitched whistle at top revs the noise is hardly offensive. Indeed to an enthusiast it is music.

But in a year or two when second-hand models appear on the market, we can understand owners having difficulty convincing buyers that the natural mechanical sounds are not excessive piston slap and bottom end bearing rattle.

Unfortunately, the Smiths rev counter set in the well-thought-out instrument panel has no red line and the only literature available is printed in Italian.

However, a quick trip to the local milk bar soon had the information translated and we were assured that everything is safe up to eight grand.

The Smiths speedo, light switch and three warning lights are mounted in a moulded plastic panel. The generator light ignites when the ignition is switched on and stays lit. Other lights are for the high beam and headlamp. All three warning lights are fitted with globes of excessive wattage and we were tempted to dab the lens with the correctly coloured paint to cut down the blinding glare at night.

The ignition key fits into a switch just below the junction of the tank and seat on the left hand side and is easily reached. Not so with the switches on the bars. They are hard to reach without moving either hand away from the grip, and are not paired (left and right) so one of them is even harder to use.

Slipping the right hand gear lever up into bottom gear allows the machine to pull away at tickover while the beautiful Conti megaphones emit a pleasant thumping noise. The frequency of the exhaust sound is deceivingly low. The bike seems highly geared but its overall ratios are similar to other 750s.

As is usual for a sports five-speeder the top three gears are quite close with second and first relatively widely spaced to enable the sportster to be easily ridden through varying densities of city traffic.

In the gears the maximum speeds are 49, 72, 91, 108 and 116 mph. Letting the motor rev out to 8000 rpm in top (which we could do only rarely) gives an absolute maximum of 123 mph.

With the extremely long wheelbase, wheelstands are next to impossible. This meant the acceleration tests were quite without drama and we were soon down to good minimum times. Unfortunately, the manufacturers do not state when maximum torque is being developed so we had to guess at around 6000 and fed the clutch in on the starting line at those revs.

The fast times and speeds are due to real 750 power going through the lightest superbike ever, but we found the performance sensation very similar to the silky smoothness of the Suzuki GT 750. Riding through a country town at 45 mph in top is perfectly smooth. Opening the throttle – even in fifth – at the end of the restricted speed zone produces the kind of acceleration with which motorcyclists enjoy outpacing other road users.

In many ways it is more fun rolling back the twistgrip at a low speed in a high gear, for the exhaust note is enough to bring back the nostalgia of the old flexible and lusty singles. During the entire test not a gear was missed and neutral was always easy to find.

All Ducatis have enjoyed a reputation for excellent handling and this latest one is no different. The bike is unaffected by irregularities on the road surface even when leant right over and going ten-tenths. The forks tipped forward for such a large amount of rake, and in conjunction with the long wheelbase, causes the steering to feel heavy at rolling speeds, but once the bike is up to operational speed the front end becomes light and sensitive with a tremendously secure self-centring effect.

Normally handling of the Ducati class takes tyres to their limit, but the Michelins are never disgraced even though the back one looks comparatively narrow on initial inspection.

Fortunately all the foot controls are well tucked up out of the way and the first thing that starts grinding is the centre-stand.

But we only touched it in testing under extreme conditions; conceivably, it could never happen in regular riding.

Many things impressed our team on test but the handling must take the top position. It is the best we have sampled.

With such power, light weight and roadholding it is easy to see why the makers have fitted it with such an efficient front disc. Japanese disc brakes are stainless steel to gain reasonable efficiency with good looks. Ducati use cast iron for the disc. This causes two rings of rust where the pads do not touch but the metal has a far higher coefficient of friction and is therefore much better at doing the all important job of stopping. It boils down to looks or efficiency.

On another bike the rear drum brake would appear to be good but on this machine it is unavoidably matched against the amazing front disc and gives the impression of being down on power. The test figures surprised us though. Quite obviously this is a rider’s impression rather than reality.

It is hard to find real criticism with the road manners, in fact not one test rider found a single point detrimental to the character of the sportster. Probably the main reason why roadholding is so good is that one of the world’s leading frame builders, Colin Seeley, designed the layout. The open double cradle frame uses the unit construction engine/gearbox as a stressed member and is light and extremely stiff.

As detailed in our May issue when we described a Yamaha-powered Seeley, the swinging arm tubes are of a large diameter with a heavy wall thickness. This makes the structure extremely rigid and more than strong enough to hold the superb chain adjusting arrangement, which moves the axle along slots cut in the tube. The adjustment bolt braces against a circular end plate to provide the movement.

Marzocchi rear units look as good as they perform and the cast alloy spring shrouds enhance their appearance as well as helping to keep out the dust.

Though the front forks have the word “Ducati” cast on the sliders they are made by Marzocchi and are very different from the Marzocchi forks on last month’s Benelli. The front wheel spindle is held by huge lugs to ensure complete stiffness of the sliders. Slackening four large Allen screws and withdrawing the spindle allows the wheel to be removed.

An innovation with these forks is that the springs and damping valves can be removed in minutes because of large-diameter screw caps fitted at their base. This is a good point for those intending to race the bike, as the springing and damping rates can be effectively altered with alternative components.

The massive forks have facilities to mount another disc, are fitted with dust caps and seals that really do their job and in many ways can be described as better than Ceriani.

In an effort to find out which one of the two top Italian suspension manufacturers produce the best forks we borrowed a Laverda SF 750 which is fitted with Ceriani and took it on a handling test with the Ducati. Though both bikes behaved excellently the V-twin did have the edge but we feel this could have easily been its 100 lb weight advantage.

As impressive as the forks are the polished alloy triple clamps, the eight bolts holding the mudguard, the method of wire mounting the flashers and headlamp, and the extensive use of plated Allen screws throughout.

Other generally impressive points about the Ducati we noticed were the stainless steel mudguards, the deep dual seat, the high standard of the welding and paintwork, the uniquely powerful headlight and the fact that two large replaceable paper element air filters are fitted – unusual for an Italian sports bike.

Another unusual characteristic of the bike – one much less desirable – was the excessive blueing on the exhaust pipes, a point which could have been rectified by the use of better tubing. We also noticed both wheel rims are made of a very soft alloy which is easy to scar. Owners need to be extra cautious when changing a tyre, and the rim is unlikely to take constant use over a broken surface.

Our time with this superbike confirmed that Ducati’s latest hybrid is sure to prove as popular with the production racing boys as it will with the man who loves saving his motorcycling for the weekend when he can derive real pleasure from using a sports thoroughbred to the full.

Although the designers have put in facilities for town riding, the full enjoyment of the 750 is felt when the city and overcrowded streets are left behind and the V-twin Ducati rider blasts out to the open country where long bends and straights mean crouching, leaning, screwing back the throttle, leaving the braking to the limit and experiencing fast motorcycling at its exhilarative best.

On a fast 125 around town you’re only playing. Twenty or thirty horsepower from an egg-whisk sized cylinder may be all right for mud-plugging or cutting costs and time in city traffic but it is only a substitute for the ultimate. A bike like the Ducati.

It has to be ultra lightweight, racing-efficient frame, suspension and braking, in tune with uncompromising power, that provides the kind of experience lesser riders dream of. And with the right skill, on the right road, with this Ducati you’ve arrived!

By Derek Pickard. Two Wheels, September 1972

Ducati’s Imola Ace: The Bike Bruno Rode

Ducati’s first Formula 750 works road racer to be campaigned outside Europe will race in Australia under the colours of Melbourne-based importer Ron Angel.

Ron attributes the bike’s appearance to a meeting almost a year ago. He and former racing companion Alan Osborne (“We’re both from the same era,” says Ron) shared a few pints and got to that friendly stage where nothing was a bother.

They decided to go to Italy.

As Victorian distributor for Ducati, Guzzi and BMW, Ron had some good reasons for staying with the idea, and Alan (of·Pratt and Osborne motorcycle dealers in Geelong) was just out to see the racing (well, that’s what he told us to print anyway).

Late last year they flew to Europe to follow the “Continental Circus”, the World Championship Grand Prix race series.

Eventually they ended up in Italy, saw Agostini win back his reputation and the honour of MV on the new four-cylinder racer on his home ground (what a way to start a business trip!) and then Ron started his factory visits. One was to be of more significance on the local scene that he could possibly foresee.

His time at the Guzzi factory was short, just enough to spend a couple of days on the accounts and making sure the new models would be here as soon as possible.

At Ducati he got a different sort of a welcome. For some reason (he can’t think how) Ron got into the racing department and became involved with the development of a new racer.

“They’ve got a bloke over there, Fabio Taglioni his name is, bloody brilliant. I’ve never met a man who knows so much about bikes. He’s the design boss and was looking after the building of the new racers,” said Ron.

At that time the racing world was preparing for the Imola 200, a race to be run on the same rules as the all-important Daytona 200 in America. The 200 miles were to be raced by Formula 750 bikes, tuned versions of production bikes with no limit placed on their develoment except that they must use the same basic engine castings (head, barrels, crankcases).

The factories were taking it seriously, and even those who had not fielded F750s before, like Ducati, Agusta and Moto Guzzi, were entering works racers. MV Agusta was getting the most publicity, though not all good. Early reports from test track tryouts said that their bike was not going as fast as it should. The factory boss, Count Dominica Agusta, had sent strict orders to the racing team that the bike must be a success at any cost.

Moto Guzzi were content to enter a slightly tuned version of their new V7 750 Sports with three disc brakes, a fairing, a large tank and a racing seat. Australian Jack Findlay arranged to join the factory team for the race.

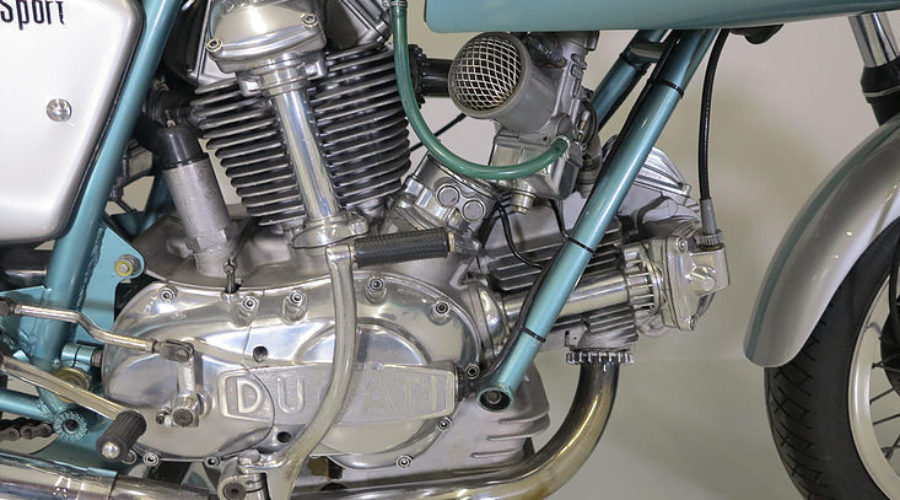

Dr Fabio Taglioni and his team were hard at work at Ducati preparing six racers based on their 750 road bike. Works rider Bruno Spaggiari had been testing various tuned machines and a final layout had been decided. The frame was to be standard, an extra two discs would help the braking, the swinging arm was to be lengthened and the motor would have a desmodromic valve gear set-up but a standard transmission.

Normally when a factory goes all out in F750 construction the frame is far removed from anything that they make for the general public, and not only in design. In some cases a different metal (often titanium alloy) is used for a lot of fittings instead of ordinary mild steel. The only modification the Ducati had in this department was a slightly lengthened and strengthened swing arm.

“I stepped into the race shop for the first time expecting to find one-off specials everywhere,” Ron says.

“I thought they were putting me on. There were six bikes in various stages of construction, and all of them on centre-stands!”

But there was sound reasoning behind the bikes that were to challenge the Agusta fours using such “around-town” fittings. Tests had shown the standard frame had the right steering setup and was strong enough to cope with the extra power. Naturally the welds had been checked and the alignment set very accurately but in the main it was a stock standard frame, hence the existing centre stand lugs, so the mechanics decided to make use of them and mount the bikes on stands!

At 29 degrees, the steering head angle is standard but the forks have a hydraulic steering damper. The 280 mm x 7 mm additional front disc on the right hand side is the same size as the standard one on the other. The rear drum is replaced in favour of another hydraulically operated disc, this time a very large 330 mm x 7 mm. Racing Konis control the rear end suspension.

Engine development starts with massive 40 mm (yes 40 mm!) Dell’Orto concentric carbs. Two inch air trumpets are mounted on the inlet side and the carbs are fitted to five-inch long alloy manifolds.

The inlet tracts have only a slight amount of swirl before the 40 mm inlet valve head. The exhaust valve diameter is 36 mm.

Super pistons are fitted to the standard 80 mm x 74 mm bore and stroke. They have three rings, give a large amount of squish at top dead centre and produce a 10:1 compression ratio. Twin plugs fire the whole lot and help keep down combustion chamber temperatures so that a timing of 34 degrees BTDC can be used. The ignition system is simply a total loss battery/points/coils.

Those huge valves are opened and shut by a desmodromic setup; the valve is opened and shut mechanically as opposed to a normal system where the cam profile opens the valve and lets the valve spring pressure shut it as the profile passes its peak.

On the Ducati each cylinder head has a single shaft-driven (by bevel gears) camshaft but the racing cams have four lobes instead of two — two to open the valves (as normal) and two to shut them (desmodromic).

This system does away with relying on valve spring pressure, which diminishes as the revs rise, by ensuring that the valve is in constant contact with a cam so the motor does not become restricted to a rev range set by spring efficiency. At the risk of confusing you we have to add the valves are fitted with springs, but they are only very small ones and merely there to seat the valves at low revs.

In the bottom end, the only non-standard parts are the conrods. They are machined out of solid billet steel which results in them being stronger and 50 grams lighter.

The big end is where the one-off parts stop. Everything else is off the production line and the same as fitted to the Ducati GT750 we tested last September. Even the clutch and gear ratios are standard. An oil cooler is the only external addition apart from the short racing megas.

The fibreglass fairing is not a wind tunnel-tested affair, Taglioni sketched it for the factory workers after they had finished making the seat and tank!

Points which stand out on the bike are the massive petrol taps, so a rider can see at a glance whether they are on, the transparent strip across the tank for instant fuel level checking and the unusual ignition switch; there’s no mistaking whether it’s on or off.

Everywhere there is evidence of meticulous attention to detail. As an experienced racer knows, it is the little things like taped cables and wired nuts that make a bike reliable in a long race.

The result of all this is a motorcycle which came to the line at Imola with an all-up weight of 392 lb and a top speed in excess of 160 mph.

More than enough to guarantee a spot in the winner’s circle? The Triumphs had as much power with less weight, the Nortons a bit less power but a fraction of the weight, Kawasakis a multiple of the power and far less weight, and MV …

Count Agusta had pushed his factory to the limit. The F750 had been developed with a shaft drive to the rear wheel, every special component known to them had been used and still Agostini was not sure of the bike’s performance. Many private test sessions were conducted and when the “fire engine” was brought to the line it could claim more development, sorting and cost than any other machine.

Paul Smart had flown to Europe on leave from the American Kawasaki team to race his relatively old Triumph at Imola, but within a week of his arrival he tired of the half-hearted effort the British factory was putting into the race and looked to other camps.

At a brief testing session at the Modena track, which is near the Ducati factory, Smart was most impressed with the new “Duke” and joined the team. He had an air of confidence before the race and even told Ron Angel at the factory the day before “This thing could just come off”.

But Ducati’s strong man, Bruno Spaggiari, knew his home track well. He didn’t have to go around many times to grab pole position. Next to him on the grid came Smart and on the outside of the front row, Agostini. His MV was immaculately turned out and was a potential flyer with its forks, frame and brakes looking identical to the type used on the 500 Grand Prix racers.

“When the flag went down Ago made a real good start,” Ron says. “He just catapulted off the line and tore off into the distance.”

Within four laps Paul Smart had closed on Agostini and sailed by down the main straight. On the next time around Spaggiari, keen to look good in front of his countrymen, also went by the MV4 on the straight. In the following few laps the Ducati pair pulled out a comfortable 15 second lead and just sat there out in front. The half-way refuelling stop made no difference.

The leading pair were content virtually to sit up, their lead was so comfortable. Agostini did not stop trying. He howled his four-cylinder MV around the circuit and then equalled the lap record speed of the Ducatis. But as Agostini closed, Smart and Spaggiari pulled away again.

Suddenly, with only a few laps to go, Agostini pulled into the pits and retired.

“The crowd went mad,” Ron laughed as he flicked through the program of the meeting. “He said he pulled out with mechanical troubles but the crowd didn’t believe him. They were convinced he just didn’t want to finish behind the Ducatis. I would never have thought an Italian crowd would have turned against their Italian world champion, but they did.”

As the leading pair reeled off the last few laps the race became a Ducati benefit.

The morning after, Ducati announced that they had made a gift of the winning bike to Paul Smart, so Ron, realising he could just be lucky and pick up one of the racers, decided to approach the managing director to buy Spaggiari’s bike while he was in a good mood.

This is where our interview with Ron Angel went flat. No amount of prompting could make him even talk about the way in which he bought the bike, let alone how much he paid for it. All we can guess is that he must have paid quite a few bucks, as when we approached the subject for the first time we noticed an expression on his wife Evelyn’s face, the kind that gives away a hint that however much it cost, she was (or had been) annoyed by the whole deal.

Whichever way he did it — shoehorn, can opener, shotgun, fistful of dollars — the fact is he did it. The bike is in Australia, to be raced!

When landed, it caused quite a stir. An Imola Ducati is no small catch and practically every motorcyclist in Melbourne rolled up at his shop wanting to have a look.

Hardly anything needed doing to the bike when it came out of the crate, just a clean-up, filling with oil and petrol, peeling off the old race numbers and writing the new owner’s name along each side. Early track try-outs have shown it to be as reliable as a low-tuned roadster. Ron notched up many fast laps at his local Calder circuit before handing the bike over to his racer, Ken Blake, with his seal of approval.

Ken is a man who came on the scene a few years ago with spectacular performances on a near-standard Triumph 650. The way the young rider threw and slid the relatively poor handling machine into the sweepers at Bathurst is still talked about today. Those spirited and determined rides earned him a job with Ron. A new, and then fantastic works Kawasaki 500 H1R racer was flown from Japan and everyone thought the combination would be invincible.

Over the couple of seasons that followed the two-stroke triple proved unreliable and handled poorly. True, Ken rocketed into the lead in many races, like Bathurst ’71, but the Kwaka either threw him or let him down.

He looks back on his time with the Kawasaki with bitter memories. But the team have learned their lesson, Ron has sold the H1R and they look forward to racing the big new Ducati.

No doubt in the coming months the bike will have the opportunity to show its true form. While the flying 350 Yamahas are hard to beat on the tracks with an abundance of tight corners, there are sufficient circuits with long straights for the V-twin 750 to stretch its legs the way it was designed to.

The years 1971 and 1972 proved bad for the Angel/Blake team. Even though Ron was respected for thorough preparation, and Ken for his skilful riding, the seemingly biggest and fastest bike that money could buy let them down. They don’t talk much of those two years that made them sadder and wiser. They now look forward to the future.

They still have Ron’s preparation and Ken’s skill, but this time they will cap it all off with Bruno Spaggiari’s Ducati.

Two Wheels. January 1973

1974 Ducati 750 Super Sport

When Ducati’s limited production big silver twin Super Sport appeared last year it was the last word in racey desirability. Already second hand models are fetching better than new prices.

But looked at dispassionately, the racing derivative isn’t much different from the base model GT. What is there about the big silver beast that merits its popular assessment as a modern classic?

Here’s road tester and 750SS owner Brian Cowan with the answer.

When they conceived the 750SS the Ducati executives unknowingly gave birth to one of the most remarkable publicity schemes a firm has ever had.

Unknowingly, because the initial idea saw the bike as a contender for Formula 750 racing, a close to stock road registerable device which could, with minor mods, hold its own on the big racetracks. Hadn’t nearly identical machines finished one-two in the previous year’s Imola, the “Daytona of Europe?”

As it was, the bike didn’t swamp the F750 scene. By the time the limited production run was on its way to customers, the formula had been expanded to allow in Yamaha 350 and 700 racers with even looser rules to follow, and the factory effort had been wound down to a semi-private level, resulting in an Imola third in 1973 and a 10th in the first heat in 1974.

The factory turned more attention to the hard-fought production racing scene with the new 860 motor, leaving the 300 SS machines built as an interesting group of specials without a definite purpose.

But were they?

Ducati’s decision was to spread the bikes world-wide, hopefully to cash in on the emerging Cafe Racer fashion but, more importantly, to promote their brothersunder-the-skin, the 750GT and Sport models.

Jackpot!

Not only were the big fellows with the silver and blue paintwork and the desmo heads snapped up quickly, but their glamour introduced the motorcycling world at large to the other, more attainable, V-twin Ducatis. Suddenly, after four years in production, Dr Fabio Taglioni’s long-legged marvels were appreciated for the moderatelypriced, good-handling, smooth superbikes they always were.

But what is a Ducati 750SS?

Well, look at it this way: Take the frame and motor of the 750GT, use high-compression pistons to bump up the ratio one point, hang them off matched pairs of conrods cut from a solid billet, replace the heads with units similar to the desmo ones used on the singles, raise the primary gearing by 10 percent, fit 40 mm Dell’Orto PHF carbs and leave the air cleaners off. Beef up the main crank bearings, revise the cam profiles and leave everything else stock.

Leave the suspension and running gear much the same but fit an extra front disc brake to the same Marzocchi forks, replace the rear drum with another disc and put 3.50 V18 Metzeler tyres on WM3 alloy rims.

Now the dress-up details: rear-set footpegs and controls, clipon bars, fibreglass petrol tank, seat unit, half-fairing, guards and sidecovers. Put Ducati Desmo transfers on the tank and 750 Super Sport on the sidecovers.

And that’s about it. Certainly the Desmo valve gear is beyond the backyard customiser; granted the conrods and pistons are fairly special, but everything else falls into the same sort of mechanical hop-up treatment given to hundreds of Honda and Kawasaki fours.

Yet somewhere along the way the alchemy is wrought. Perhaps it’s the fact that the SS is a full factory job, designed completely and competently by experts; perhaps it’s the way the racer theme dominates; but the bike is one of the most eye-opening ever made.

Standing close can destroy the illusion. Not that detail finish isn’t good, but one catches the simplicity which is the other feature of the SS. Can something that basic look really good? Believe it! Step back 10 paces and view the machine from any angle.

Gradually it dawns. The SS looks better than all the other Cafe Racers because of the unique V-twin motor, displayed to better advantage than in the standard GT, or even the racy Sport.

The paint scheme completes the effect: silver grey with a central stripe of light grey-blue, and repeated on the lower half of the fairing and on the frame.

There are no options. That’s the way an SS comes.

The bike is more than a pretty face. In important areas it comes closer to the ideal road motorcycle than many others.

Take the question of weight. The Ducati 7 50s are renowned as being among the lightest of the big machines, with a quoted heft of 185 kg (408 lb) dry for the GT. This places it neck and neck with the 750 Norton Commando, traditionally the featherweight of the big brigade.

The SS goes even better – a claimed 180 kg (396 lb) dry – to put it squarely into the champion’s seat in the 750-and-over bracket. And we feel that claim is pessimistic! With 17 litres of fuel and four of oil on board, our test machine tipped the scales at 191 kg (420 lb), wringing wet, ready to roll and some 45 kg lighter than a Kawasaki 900!

The tough girder-style frame which uses the crankcase as a stressed member is suspended on the best of Italian running gear: Marzocchi suspension units, Borrani rims, Lockheed pattern Scarab brakes. The Europeans seldom miss when designing steering geometry and the SS is no exception. The wheelbase is slightly shorter than the first of the GTs now that the firm has dropped the offset axle forks. Steering is still deliberate but not overly heavy. Its steadiness is beyond question. At any speed above a walking pace the bike feels clamped to rails.

Combine the light weight, small and slippery frontal area, and a motor delivering more than 45 kW (60 hp) at the rear wheel, and you have a performer of the first order.

When the initial view is of a racer equipped with just enough equipment for street legality, the tractability comes as a real shock. No snorting, peaky, cammy beast this one; the torque band doesn’t start quite as low as the GT (the big carbs see to that), but above 2500 rpm the SS is a dream, a good-natured, easy-going, two-wheeled tractor.

There’s no vibration, no chain snatch, nor any reluctance to go when the wick is turned up. Fourth gear at 60 km/h has an easy 2700 rpm showing on the tach and all the acceleration you could want on tap.

The big carbs are equipped with accelerator pumps and deliver quick response from any throttle opening except a dead slow idle.

Starting demands a little attention for consistent results. Each carb is fed by a separate tap, although the two fuel lines have a bridge tube between them. No choke is fitted, so the float bowls have to be flooded.

The test bike especially was critical on that point. Any stop of more than five minutes demands the full cold-start procedure. Following it faithfully and holding the throttle steady and barely open resulted in no more than a couple of kicks to start. Any other procedure was likely to be doomed to failure.

Strong as the Ducati SS is on looks, it’s even stronger on sounds. We’re not likely to hear fourstrokes as loud as this again but the flat bark of the two long exhausts is a magnificent sound. We can only hope that when the company quietens its twins the basic note isn’t lost.

Internally, the motor also makes a fair din. With not a chain in the entire unit (everything is run by beautiful helical-cut gears, many of them right-angle bevels), the distinctive noise is a racy thrashing of metal to metal, not unlike the sound of high-performance Italian car motor.

It may be noisy, but it ain’t a shaker. Like the GT and the Sport, the SS is one of the smoothest bikes on the road, thanks to the 90 degree Vee layout. Firing pulses are spaced at 270 degrees and 540 degrees apart, enough to make the idle slightly off-beat, but perfect for balancing out the complex loadings on the crankshaft.

The test bike had a range of minor vibrations at 4000 rpm, but no worse than a Honda four. Considering that the motor is mounted solidly in the frame and the footpegs through which the vibration comes are solid steel without rubber covering, it’s obvious the motor is very, very smooth.

While the mid-range torque of the big mill and its easy tractability are the first favourable impressions when riding, the bike’s overall comfort is equally as impressive. Let’s face it, Cafe Racers are seldom long on comfort, and to get the good looks one often has to sacrifice practicality.

But the Ducati scores well. It’s not a BMW, naturally, and after the first longish ride the wrists are conscious of the weight they’ve been supporting but by and large it’s nowhere as fearsome as it looks.

Even the strain on the wrists disappears once a few days’ riding has educated the relevant muscles. There is no back-ache, and the bars and pegs are well-placed relative to one another, while the bars have an ideal angle. The little seat has utterly skimpy padding and feels, at first, to be an instrument of torture, but compensates by locating the bot perfectly at all times. Because much of the rider’s weight is taken on the high rear-set pegs the lack of seat padding never becomes a real drag.

Which is not to say the SS is the ideal tourer. Far from it! There’s room for one body only and very little luggage. The tail section is hollow and reached through a zip at the rear of the padding but is useful only for a few tools and similar small items.

In addition, the lack of aircleaners prohibits riding on dirt roads.

Nor is the SS the perfect commuter, but the reasons why not can be applied to all big bikes. City speeds are below where it feels completely comfortable and the ultra-steady high-speed steering is slightly vague at a walking pace. The use of identical tyres front and rear compounds the feeling, the big Metzelers respond better when being subjected to the stress of 10/10ths cornering.

Race-bred suspension also proves to be overly harsh for the indifferent surfaces found in Australian cities. Under brakes the forks tend to judder when subjected to ripples and patches.

The response to compression damping is hard at both ends, although the bigger bumps and hard braking use up all the travel.

With two discs forward and one aft, and all of them gripped by double-piston calipers, the SS has superb stopping power. By using a master cylinder of the same dimensions as that on the single front disc on the other 750s, the factory has given the bike a certain touchiness which needs to be catered for. Lever travel is longer than usual and enormous braking forces are generated with little effort. Truly, this is a bike on which the front wheel can be locked at 100 km/h with only one finger.

Gently, gently is the way to go, and with a small amount of practice the bike proves to be a swift, safe and progressive stopper.

If strengths and drawbacks of the 750SS seem to point it towards the racetrack, your guess is right. The SS is happiest being ridden up around the 9000 rpm limit which the complex desmo valve gear allows, hurling into bends on the outside tread of the big sticky tyres, plunging down from 200 km/h-plus under the action of the extremely good brakes, tracking steady and true with the undersides of the exhausts hung up on the tarmac.

Yet the bike also comes out as a really good road bike; if not an ideal all-rounder then a great short-haul mountain-road burner. And literally nothing has to be changed from stock if an owner wants to road race. Not tyres, not suspension, not brakes.

As such, the SS stands alone. It is the modern equivalent of the BSA Gold Stars of yore, on which clubmen riders would travel to a race meeting, remove lights and head for the track. And even more so than the Gold Star, it stands as the definitive expression of the Cafe Racer philosophy, a lean and good-looking tribute to the colourful world of the tarmac tracks.

The Ducati 750SS has to be acknowledged as a modern classic.

By Brian Cowan. Two Wheels, February 1976

Falloon: The Classic View

The Ducati 750 owes its existence to the great engineer Fabio Taglioni. Without Taglioni it is unlikely that Ducati would be where they are today as a motorcycle manufacturer and their current success has been built very much on the achievements of the 1970s.

When Taglioni joined Ducati in 1954 from Mondial, the motorcycle production programme centred around the small capacity Cucciolo. These were motorcycles and mopeds that were ideal for basic transportation but were very limited in any other way. Taglioni wanted to build racing and sporting motorcycles and had an extraordinarily creative and fertile engineering mind. The success of Taglioni’s designs led to the success of Ducati as a company and the early history of Ducati as a motorcycle producer is also the story of Taglioni’s involvement. He was extremely prolific, and while every design may not have been excellent, the best were unequalled. And Fabio Taglioni considered his best design over a forty-year association with the company was the bevel-drive V-twin. Not only is that engine a truly magnificent design, but its success contributed to Fabio Taglioni’s reputation as one of the all-time great motorcycle engineers.

During the 1950s and 1960s Ducati had much success with their overhead camshaft singles but the arrival of the superbike era in 1969 saw them expand into larger capacity motorcycles. Although still part of an Italian government conglomerate, Ducati now had new managers, Arnaldo Milvio and Fredmano Spairani. For the first time since Dott. Montano in the early 1950s, Ducati had a management enthusiastic about motorcycles and racing.

When Fabio Taglioni was given the go-ahead to design a 750cc engine in March 1970 he knew that he would have to make the most of the limited resources available. That meant utilising much of the technology of the current singles. It seems to be a simplification, but basically Taglioni took two 350cc singles, and placed them 90 degrees apart on a common crankcase. He wanted something that would work immediately and could be put into production with minimal development. Never one to follow the crowd, it would also satisfy his desire to create a unique, large displacement, twin cylinder motorcycle.

The 90-degree V-twin gave Taglioni the chance to put some of his engineering ideas into practice. When I asked him why he chose the 90 degree layout he replied, “It provides perfect primary balance, hence is very smooth, and with the two con-rods mounted side by side on one crankpin it is barely wider than a single. We could place this engine very low in the frame, giving a low centre of gravity. The cooling to both cylinders is also excellent. If there is a drawback it is in the length of the engine that necessitates a longer wheelbase and it is more difficult to silence.”

Because he drew so much on his experience with the singles, the 750 engine was running within two months. To quote Taglioni again, “This engine was perfect right from the start and because I could build it to my specifications without any outside pressure it was the best design of all my engines over the years.”

There were some noticeable deviations from the overhead camshaft single, notably in the use of coil rather than hairpin valve springs and a direct gearbox with the secondary shaft mounted above the primary shaft to reduce the engine length. Bearing sizes were increased over the singles, and most shafts uprated. The camshafts were now supported by three bearings instead of two and the vertical bevel shafts’ diameter increased to 17mm from 15mm. This made the drive coupling much stronger and less prone to wear. The rocker pins were also increased in diameter to 10mm. The camshaft drive was by an expensive set of nine helical toothed bevel gears, with the ignition points located between the cylinders. The finning was different for both cylinders, with the front and rear cylinders offset 22.5mm.

Where Taglioni could have been criticized was in his retention of what was, even in 1971, an obsolete cylinder head design. Still using the 80-degree included valve angle of the 1954 Gran Sport, the cylinder head design would always be compromised for racing even though the significant offset of the ports (15 degrees inlet and 30 degrees exhaust) provided excellent swirl characteristics. The valve sizes of 40mm inlet and 36mm exhaust were moderate but what was more notable was in the way the cylinder head had been designed for desmodromic valve gear from the outset. Even the original castings provided plenty of room for closing rockers and only barely enough for valve springs only moderate length. What’s more, there was always enough metal around the inlet ports to make it large enough for the use of 40mm carburettors.

By 25 August 1970 the engine was installed in a frame that used the engine as a stressed member like the singles, but with twin downtubes, and being tested on the Modena autostrada. This prototype shared many parts with the singles (instruments, mufflers) and had a Fontana 250mm double-sided twin-leading shoe front brake. Carburetion was by Dell’Orto 29mm SSI remote float bowl carburettors. A month later, with clip-on handlebars and ungaitered forks, it was officially displayed to the Italian press at the Modena circuit.

In October 1970 Milvio and Spairani approved Ducati’s re-entry into the world of Grand Prix racing, this time with a 500 V-twin. The 500 differed considerably to the 750 and pouring all resources into its design undoubtedly slowed up the larger bike’s development. Six months later Taglioni had his six-speed desmodromic 500 twin running. The purpose of the machine was not so much as to win races as to show the soundness of the V-twin concept and promote sales of the 750. However, unlike the 750, the 500 suffered from reliability and handling problems. In December 1970 a frame was commissioned from Colin Seeley in England and both four-valve, two-valve cylinder heads, and fuel injection were tried. The failure of the four-valve head, and the constant trouble with the Ducati Elettrotecnica electronic ignition, led to Taglioni’s distrust in these ideas. He would have persevered with fuel injection but no sooner had he fitted it to a 500 in March 1970 than it was banned by the F.I.M., ruling it as a form of supercharging.

The initial 500 racer weighed 135kg with the 74×58 mm engine producing 61.2 horsepower at 11,000 rpm. As no alternator was fitted the engine was narrower than the production 750. It was also much shorter and the wheelbase was kept down to a respectable 1430 mm. Carburetion was by two remote float bowl 40mm SSI Dell’Ortos and the clutch was dry. By June 1971 Phil Read tested the bike with the Seeley frame but still wasn’t totally satisfied so Seeley revised it.

A 750 version of the Seeley-framed 500 was also built for Mike Hailwood to ride at Silverstone in August 1971. He qualified sixth fastest for the Formula 750 race but decided against riding it, claiming that it didn’t handle well enough and needed more development. This was the first 750 desmodromic racer, but apart from the engine dimensions, shared little with the later Imola bikes.

Throughout 1971 the 500 was campaigned by Read and Spaggiari, but it was never going to be a match for Agostini and the three-cylinder MV. The go ahead was given by management to develop a water-cooled three-cylinder fuel injected double overhead camshaft racer 350cc racer but only an engine was ever built. Remembering the disaster of the earlier twin cylinder 125 and later 250 and 350s, Taglioni was not too keen on the idea, so Spairani bought the design from the British company Ricardo. Already obsolete, bench tests proved very disappointing, with only 50 horsepower being made at 14,500 rpm.

The 500 twin was developed slowly during this time, finally achieving 71 horsepower by the end of 1972 with the aid of Dell’Orto PHM 40A carburettors. The four-valve version didn’t even get to this figure, only making 69 horsepower at 12,500 rpm. By now twin Lockheed discs graced the front end, along with a Lockheed disc on the rear, but the success of the 750 at Imola had totally eclipsed the 500. For 1973 Spairani sent the 500 engine out to Armaroli, another Bolognese company, and they designed a set of four valve cylinder heads with double overhead camshafts driven by toothed rubber belts. This final version produced 74 horsepower at 12,000 rpm but was only raced at selected Italian meetings by Spaggiari. The Armaroli engine was the way of the future though and Taglioni drew on his experience with it when he designed the 500cc Pantah engine a few years later.

Further prototype 750 street bikes appeared during the latter part of 1970. One with twin Dunstall front disc brakes, Amal concentric carburettors and a revised frame was shown at the London show in January 1971. When Taglioni saw the Seeley frame for the 500 with its special Seeley chain adjusters, the snail-cam Scrambler adjusters were discarded. The final production version of the frame owed much to the Seeley, and carried through right until the last 900 Super Sports of 1982.

When the 750 finally entered production, nearly twelve months after the first prototype had been tested, everything was immediately right, except for the marketing. The 90-degree V-twin looked strange and unusual to those used to Honda fours and Triumph and BSA triples and initially faced considerable buyer resistance.

That was until that memorable day on 23 April 1972. As Fabio Taglioni put it, “When we won at Imola we won in the market too.” That day also saw the transition of Ducati. Before Imola they were a minor manufacturer of predominately single cylinder motorcycles, but after Imola they could take on the best in the world and beat them. For Ducati and Taglioni it was the start of a new era.

By Ian Falloon