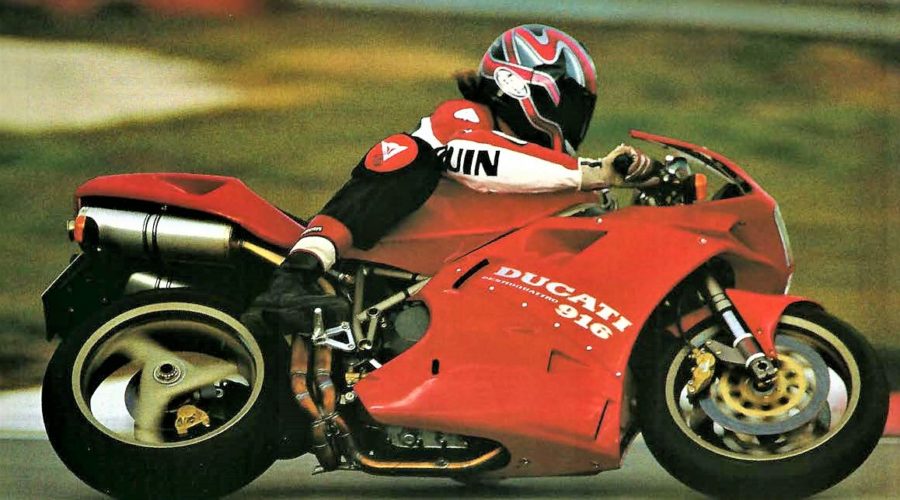

1994 Ducati 916

ITALIAN motorcycles are great handling, if quirky at times, and soulfully designed, if lacking in the finishing touches. Right? Wrong.

Enter the Ducati 916, a phenomenally potent sports motorcycle which represents not only a giant leap forward from the 888, but a major shift in thinking for Ducati. The 916 is an Italian motorcycle to its core but without, it would seem, the rotten bits you’ve got to swallow before getting as far as the core.

From its overall design philosophy to its attention to detail, from its engine to its handling, the 916 impresses. It is so much more than the 851/888 it replaces that the difference is hard to credit. And this probably – no, definitely – has a lot to do with the team which put most of it together. The 916 is, apart from the engine internals, brought to us by the same people who brought us the Cagiva 500cc GP racer: the Cagiva Research Centre (CRC).

Cagiva’s GP riders, as well as Ducati’s Superbike stars, lent a hand too. Massimo Tamburini, of Bimota fame among others, and Massimo Parenti headed the design team. It was significant that I was in Italy at the request of Cagiva Trading rather than its Ducati arm. While it was Ducati SpA which looked after the engine internal modifications that took the 888 to 916cc, CRC has made this bike what it is.

I was among a handful of journalists invited into CRC – not the first time the Centre has ever been opened to the press, but certainly a rare moment.

It is a small setup in an industrial estate beneath the towering walls of San Marino, and you could eat your dinner from its tiled floor. There, Parenti, a thin man of about 178 cm with long fingers and a quick smile, ran through much of the 916’s detail. He was clearly excited by everything he showed us, even dragging out the original blueprints to point out demanding aspects of design piece of design and eagerly running to grab an Allen key to demonstrate a particularly smart piece of design simplicity.

He kept referring to the GP bike, which he credited as a major source of knowledge and, indeed, inspiration for the 916.

To get a good idea of what the 916 is, you must start with the little things. Like the fact that its various bolts and quick-release fastenings were all designed by CRC specifically for the machine – and, it must be noted, for all future Ducatis. Like the injector assembly bodies, which have the fuel lines cast inside them to minimise the plumbing.

Like the simplicity of unclipping the bodywork, air intakes, tilt-up seat unit, fuel tank, etc, to speed up servicing. Like the beautiful cast-alloy headlight support which also holds the fairing/mirror stays, instruments and some of the electrics, and can be removed as a complete unit by undoing two bolts and an electrical connector. The wiring and plumbing around the engine is positioned so that the engine can be dropped out by just unplugging a few wires and undoing its three mounting bolts. The tank also forms the airbox cover, thereby doing away with one part and adding simplicity.

There is so much more too, but as Parenti finally said after an hour or so, throwing up his arms, “Do you want any more?”

The seven kilograms shed between 851 and 916 Stradas, Parenti told me, “come from many small changes. It may not seem much to lose a few grams with a new fastener but when you have many fasteners it is important. Even the suppliers had to fight and spend money to save a few grams.”

CRC’s work will also save on servicing costs, one of the banes of 851 ownership. “We don’t know yet how much cheaper,” said Parenti, “but it will be significantly.”

The 916 shows design standards and detail which do not just rival Honda, they would be worthy of Bimota. One of the attractions for me when I bought my Bimota db1 was its engineering beauty; I have sat and stared at it, run my fingers over it, in admiration. The 916 even outdoes the Bimota’s purity in many areas. And Parenti promises we can expect this to carry over to future Ducatis as well.

If there is art in the new 916, there is also practical integrity. The new chassis, still the traditional Ducati trestle of chrome-moly tubes, is said to be twice as rigid as the 888 frame and now reaches down to the swingarm pivot, helping add to that rigidity and also bracing the crankcases, which previously took all the stress from the swingarm. The frame is in a diamond pattern, wider at the top and front, which is stiffer than the parallel 851/888 design. The SP model will feature an optional carbon-fibre airbox which is said to add a little more bracing, too.

Another improvement comes from the triple clamps. Top and bottom clamps are machined together in pairs, so any tiny error is matched top and bottom and not translated into forkstressing torque once assembled. The whole steering head area is so rigid, said Parenti, “that the fork has to be perfect. In most bikes there’s some flex but not in the 916. Showa (fork and rear shock supplier) was impressed because it was so good.”

CRC also patented a unique feature for the 916. The steering angle – rake and trail – is adjustable to two positions by means of simple eccentrics in the steering bearing housing. The wheelbase is not altered by the process, which requires loosening two pinch bolts and rotating the eccentrics. The choice is either 24 degrees/94mm or 25 degrees/100mm. And if it’s stability you’re seeking in adjusting the steering there’s also the two point mount for the standard steering damper – and chalk up another patent.

The more obvious part of the new chassis is of course the single sided swingarm, claimed to be both more rigid and quicker for wheel removal, though CRC rates its aesthetic value at least as highly. The high-mounted exhausts add to its striking appearance and accessibility. A new rear wheel was required to suit the swingarm, so the three-spoke pattern design was drawn, and a front three-spoke wheel to match.

CRC’s only contribution to the engine was to redesign its side cases (repositioning the water pump slightly in the process) to make it narrower. “We did this so it could get closer to the dimensions of the 500cc GP motorcycle,” said Parenti. The chamfered cases add a little more to the lean angle possible on a race track and slick tyres.

An extra two millimetres of stroke takes the 888 engine to 916 cc. The longer stroke adds to the Ducati’s midrange performance, while revisions to the intake system, including a larger airbox, add top end power. At 9000 rpm the power peaks at 83 kW, but is claimed to drop by less than a kilowatt by 10,000 rpm.

One look tells you the exhaust is new, its oval-section mufflers poking out from under the seat unit. Other changes include a bigger radiator, an oil cooler for all 916 models (only the 888 SP had one before) and a stronger alternator.

Parenti was at pains to point out that CRC’s design team looked at the 916 project as a single entity, not a union of different sections. Hence the bodywork was designed in conjunction with everything else, and was seen as being just as important as anything. It was not shaped after the event. The result is a bike which looks as compact as it is and which is very aerodynamic.

Compared to the 888’s fairing the 916’s is claimed to be worth 10 km/h in top speed.

It also looks incredibly beautiful and sporty. Perhaps the exhaust headers spearing up in front of the rear wheel aren’t the most pretty things around, but there is no angle on the 916 which isn’t attractive.

What also strikes you when you see it in the flesh is its size – little more than a 250’s bulk. As soon as you settle onto the seat you know the 916 is going to be different from its predecessor because the size isn’t there. It is not so tall.

Sitting proud among the instruments is a lime green on black tacho, above a black on white speedo and a small temperature gauge. The warning lights are a neatly packaged cluster nearby. In front of the tank, mounted side ways, is the steering damper, with the key behind it.

Setting the fuel injected 916’s fast idle circuit for warmup happens by rotating the throttle forward until it clicks. The throttle cable activates the “choke.” To cancel, just push the release button near the grip. Another simplified function.

And when the 916 does burst into life, it’s with the familiar Ducati rumble.

After well over 24 hours in aeroplanes and airports, plus the drive from Bologna to Riccione and the hotel (with some sight-seeing thrown in – you can’t work the whole time) my moment finally came the next morning at Misano’s racetrack.

I cruised out of the pits to find the lie of the track and immediately felt comfortable with the new Ducati. Its ride position is sporty but accommodating (unless, perhaps, you’re much taller than my 182cm) and the low-end and midrange willingness of the new motor was as good as should be expected of a big V-twin.

The big change, though, is in its handling. The heaviest of the older eight-valvers felt slightly tall and top heavy but that’s been banished completely. The 916 is small, light and tight, steering with the utmost precision the moment you tell it to. Compact is the word, the centre of gravity so well placed it gives a 50/50 front-rear weight bias and very responsive steering.

When the pace got hot the 916 just got better, despite the roadgoing suspension which hadn’t really been set for the track as I might have liked. But the Ducati was stunning everywhere, from the very tight, awkward left hander that is turn three, right through the following left handers which form a sweeping, ever-faster succession onto the back straight. Whatever the speed, whatever the corner, the 916 was excellent.

Many of Misano’s corners are a bit bumpy but the only time the 916 ever gave signs of feeling them was under full acceleration out of one particular corner over bumps. Then it would twitch its handlebars briefly but without fuss. None of those bumps were what we find in Australia, though, so that’s a question yet to be answered.

The 916 is without a doubt one of the best I’ve found for braking in corners. It was uncanny how easily it could be steered still braking firmly up front. It means the 916 can leave its braking till the last moment. Only the telelevered BMW R1100 and Omega-framed Yamaha GTS1000 feel more unaffected when you need to wash off more speed mid-bend.

At a corner’s apex the Ducati can lean so far you’d think your ear could touch down. It’s the high, narrow footpegs which finally do though, with the Pirelli Dragons still holding their own.

CRC chose a massive 190/50-17 rear tyre for the 916, which I figured was overkill on a roadbike until I tried getting on the gas hard and early in a tight corner. The 916 has enough potency to have the sticky, very fat Dragon stepping out.

The excellent ergonomics help out then. Shifting weight rapidly is easy, as is gripping the thin, sculpted tank with your thighs. I could relax more on the 916 than on most other bikes through a corner because I could support myself so well with the seat and tank.

The small but aerodynamic fairing’s effectiveness is readily felt at speed. As soon as you sit up or poke out a knee the wind suddenly grabs you. You have to tuck down tight to make the most of the bodywork but even I could do it without contorted discomfort.

The 916’s power comes in a long surge as the revs rise, seeming to plateau before the 9000 rpm peak and holding past it. Indeed, several times early on I found the rev limit just past 10,000 rpm when I wasn’t watching the tacho. In several of Misano’s corners it was better to short-shift the 916 and use the prodigious midrange to push through.

Response from the revised fuel injection is instant. Exiting one of the left hand bends and banging up into third gear popped the front wheel up every time.

Shifting is positive and I found no false neutrals. However, you’ve got to be a bit more definite about your foot movements than you might on most Japanese superbikes. The gearbox ratios worked well enough for Misano and I’d guess they’ll prove nearly spoton for the street, too.

The brakes are unchanged from the 888 but are more effective on the lighter, more steerable 916. They don’t have the initial bite of Japanese bikes’ brakes but progressively pour on the stopping power. Many times the back end came floating into the air behind me as I nailed the front brakes for the 180 degree turn at the end of the back straight.

By the end of my time with the 916, with a decent mental map of the track and full confidence in the Ducati, I strung a few fast laps together. Each lap the Ducati seemed to mock me, asking for more. Only a slide from my over-eagerness to get power down early out of the chicane slowed the 916’s progress. I revelled in its brilliance before getting off the bike and realising I wasn’t particularly drained by the effort, either.

If first impressions really are so important – and first impressions are basically what these launches are about – the Ducati 916 has outdone the Honda CBR900RR, a very hard act to follow. On the track and inside CRC, the 916 screamed excellence. No-one, especially Ducatisti, would have imagined how much better it is than the models which came before it, nor what a competitor it should be for other sports bikes. Then you have to factor in the attention to detail and outright quality which CRC has brought to it.

Such excellence has added to the price, naturally, and the 888 wasn’t cheap in the first place. The first batch, due in Australia in April or May, are tagged at $24,995 but it is, in my mind, money well spent.

The 916 heralds a new era for Ducati, an era still full of tradition but adding the nearest thing to perfection which 25 grand can buy.

By Mick Matheson, Two Wheels, April 1994

Guido from AllMoto owns a Ducati 916. Read the love story here.

Ian Falloon has the definitive account of the 916’s design and development here.