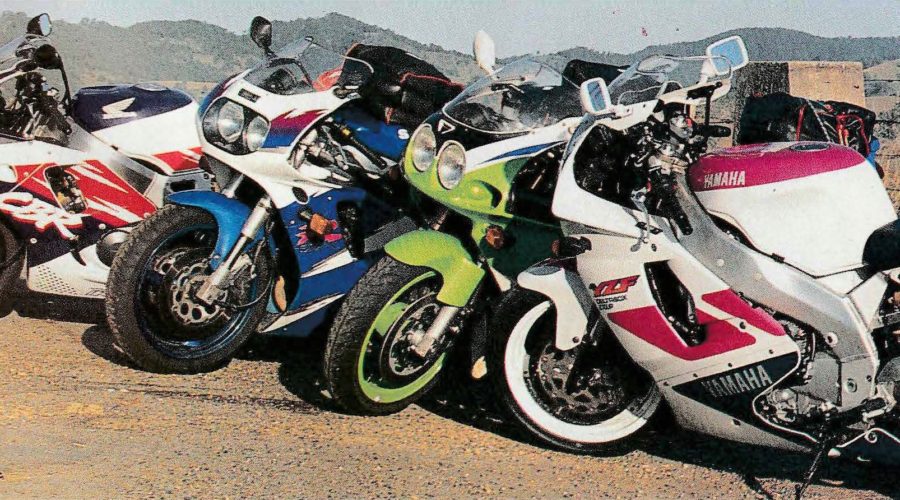

Comparison: 1993 Honda CBR900RR vs Kawasaki ZXR750 vs Suzuki GSX-R750W vs Yamaha YZF750R

Like Honda’s 900 last year, the YZF had the Sunday road cafes abuzz with excited riders, eager to see what Yamaha could come up with after so long out of the affordable 750 market. Time got closer and the tension built when they learnt it was going to be better than the exclusive OW01.

Even the weird and wonderful GTS1000 didn’t detract from the 750’s entry. I remember a couple of months ago, with the GTS, being collared by three late-teen blokes who asked, “What’s the new Yamaha like then?”

“Good,” I said, looking at the red monster, before being impatiently corrected. “Not that one, mate. What’s the YZF750 like?” Stuff the high-tech fanfare, we just want hard and fast rock’n’roll.

And that’s what we all expected from the 750. More claimed power than the Honda CBR900RR, less weight than either the Kawasaki ZXR750 or Suzuki GSX-R750W and steering dimensions close to the confident Kawasaki’s.

But there’s a lot more to on-road manners than what’s on the the spec sheet, so we gathered together the whole gang of sports bikes and headed for the most rigorous roads any bikes could ever meet.

Has Yamaha built 1993’s best sporting 750-class motorcycle?

Yamaha YZF750R

Our photo session happened in glorious weather at Eastern Creek and told us the YZF had the credentials for speed. It had a race bike’s ability to get power to the ground and blast fast away from apexes. It steered the tight lines demanded by Eastern Creek. This was no surprise after the Phillip Island debut but we quickly pinpointed one potential worry: this test bike’s brakes didn’t inspire like the debut bike’s had. There was a judder in the system and less feedback than there should have been.

But this bike had already gone down the road twice, so perhaps it was asking too much to expect perfection. And then I made it three times …

It was a front-end lock-up and the bike fell so fast I had no time to unlock. Just whack! I didn’t expect it.

Half a dozen identical passes, under medium braking, had occurred without mishap: hold the brakes on gently, maintaining slight drive to keep the pose for a few seconds, then peel off and increase braking. Simple. Halfway through the prolonged posing bit on the fateful lap, I went down. We’re still wondering about it. Did I subconsciously stuff up or did the brakes grab? If I knew it was my fault, I’d admit it; if I knew the brakes were guilty I’d say so; but I can’t honestly say either.

Those powerful six-pistons-a-side brakes can be very good. However, there have been other reports of problems – and crashes – with them. “Unpredictable at times” might be a fair criticism but the irony is that, on this test bike, we had no problems using them to maximum effect in a straight line once they were warm. The juddering disappeared and it was possible to pull up with the front tyre chirping merrily on tiny road lumps.

At one stage we removed and then replaced the pads, making a small but noticeable improvement before the miles returned things to what we had at first. Port Macquarie Motorcycles had the whole front end apart for us at one stage, to no avail. Robbie Thompson at Bells Line Motorcycles measured 0.5 mm runout in one disc and a slightly out-of-true front axle. Yamaha is currently checking it over but we won’t get it back in time for this issue; an update will follow next issue. (The update story follows this test – Ed.)

If the brakes didn’t meet expectations, we got encouragement once we got far enough into the ride to compare engines directly. Runs on tight, winding roads on the Yamaha had us sporting huge grins, thanks to inspired drive out of corners. Like its 1000cc brother, the Yamaha 750’s 20-valve, EXUP engine really cracks at high revs, yet delivers strongly through the midrange. You get all the right noises from the rider’s seat when the engine comes on song in the 5000 revs before redline.

The EXUP exhaust valve, which helps boost low and midrange power in a motor tuned for top-end go, makes a real difference and the grunty, bigger Honda was the only bike which could top the YZF750’s great mid-range pace.

Accelerating hard from stationary to wimp-out had the Kawasaki only fractionally behind the Yamaha. Come the Honda’s turn and the 900 eased gently away in the roll-ons and just won out in the top-end frenzy. The Suzuki was forced to gracefully admit defeat throughout.

All these differences would be elementary if the Yamaha didn’t get around corners too. It did that superbly, on a smooth road. Its nimbleness compares well with the Honda’s and the YZF feels like a bike with a minimum of unsprung weight. Also in favour was its sureness up front as it tips in – almost as good as the Kawasaki’s. That combination gave it the thumbs up for scratching. Smooth roads also bring out the rock-solid roadholding of the Yamaha, at any speed. Trouble reared its ugly head again on bad roads. As with the brakes, it was trouble which, theoretically, shouldn’t have happened. The YZF’s geometry isn’t that radical. Yamaha is also checking it out before we re-evaluate next issue; but as it stands, we got scared by tyre-screeching, wrist-straining tankslappers on more than one occasion, when the other bikes handled no worse than skittishly. This instability was enough to fray nerves and force conservative entries to corners.

Heavier damping oil (five weight, up from the super-light 2.5 weight from the factory) only spoiled the forks’ rebound stroke, yet we felt the standard oil didn’t allow full use of the preload adjustment. Damping adjusters, as fitted to the other bikes, would be a welcome addition.

The rear suspension seemed to cope well. A bike’s rear can significantly affect the front. The YZF’s rear spring starts as firmly as you’d like it for lighter riders (about 65 kg) on its minimum preload setting and goes up seven steps on the easily-adjusted collar from there. The multi-adjustable rebound damping is sensitive to each click of the adjuster but can be set well to match the spring’s settings. When the front did go wild on those occasions, the back end tracked well enough to keep the bike from losing control.

Even on smooth roads, most riders won’t worry about cornering clearance, the ‘pegs eventually warning of approaching limits well before disaster. The Battlax tyres cope very well until too worn. The rear brake is fine and not too sensitive.

Clutch take-up is progressive and the gearbox is very positive, with no missed gears, but slightly harsh. It’s not the slick shifter the Suzuki is.

Sitting on the YZF is much like being on the Honda. The footpegs are not too high and the ‘bars aren’t too far forward. On long runs it was the most comfortable, thanks to help from the more protective, tall-screened fairing and relatively upright ride position. The engine sends out too much heat for the legs at times, though. Pillions aren’t so well considered, with no grab rail and cramped leg positioning. The tidy-looking single-seat cowl may not often come off …

Those cats eyes headlights look flash and give good, sharply-defined penetration without as much spread as the others. Four lugs on the sub-frame sufficed to secure the Quin seat bag we used and the YZF willingly carried the magnetic Quin tankbag.

Yamaha has finished the bike neatly. The tacked-on look of some parts, notably the tail lights, is disappointing but doesn’t really spoil the bike, and is outweighed by the quality of the majority of parts, including switchgear, adjustable levers and good mirrors.

Assuming the brakes and front-end stability on this bike can be set up to our satisfaction, there’s no reason why it can’t be considered the best all-round sports 750 on the market. We’d like adjustable damping up front but otherwise the great engine, excellent steering and feel of the YZF are class-leading. The Yamaha may not quite have the grunt of the bigger Honda but it feels as light and more confident (just) in corners and is as much fun to get on the gas.

We’re confident about the brakes after the lessons learnt at the Phillip Island debut but the front end leaves some doubt. If you ride hard on rough roads – and there are plenty of those in Australia – it’d be worth waiting for our update.

Honda CBR900RR

So it’s a 900. Who cares? The fact is the FireBlade is, for all intents and purposes, a glorified 750. It’s low on weight, short in dimensions and, if you believe the paper claims, a poofteenth less powerful than the new Yamaha 750.

But you pay for the extra 150 cc. The 900 is the most expensive bike of the four by a few hundred dollars.

Just sit on the Honda after sampling the Yamaha and you know the two are going to be close. They’re of the new breed of short, sharp sports bikes which have the handlebars close to the knees and footpegs almost comfortably forward. They feel light on the road and light in the controls. The Honda only has a few kilos advantage on the Yamaha, so the differences shouldn’t be great.

In some ways they aren’t. Perhaps the Honda doesn’t steer quite as directly but there’s little in it. They steer the precise line you pick and do it fast.

Yamaha EXUP and five-valve technology always was good and the Honda’s engine doesn’t have it all over the Yamaha’s smaller one but Yamaha’s claim of 92 kW doesn’t live up to scrutiny when the 91kW 900RR leaves it behind through the top end. The Honda takes a small lead through the midrange and then, about two-thirds of the way to redline, it eases ahead and keeps doing so until discretion calls for the abandonment of valour’s pursuit. Lifting the front wheel off the deck happens more enthusiastically on the 900, too. Honda retains the crown.

You could rightly expect the Honda, with its most radical rake, trail and wheelbase dimensions, to be the twitchiest of the four over rough surfaces but the thing is so well engineered it left the Yamaha tankslapping in its wake, soaked up the bumps better than the Kawasaki and wasn’t much less confidence-inspiring than the steady Suzi in the rough.

Cruising the transport sections on the Honda is as comfortable as on the Yamaha. Most riders are left sitting relatively upright, without too much wrist pressure and the footpegs are well placed, scraping for hard riders but never getting in the way.

Kawasaki ZXR750

The green machine almost ran head-to-head with the Yamaha in sheer acceleration through the gears. But not quite.

Surprisingly, the Kawasaki pulled away from the Yamaha in low-speed, low-rev roll-ons but through the midrange the Yamaha took first place. Unfortunately, the re-tuning of the ZXR for ’93 has left a bit of a hole in the midrange. Perhaps the extra weight and slightly taller gearing let the Kawasaki down in top gear overtaking moves, too. Whatever, the Yamaha takes victory in the engine stakes.

The lower screen, longer reach to the ‘bars and vibier nature of the Kawasaki helped bring a warmer reception for the Yamaha, too.

This bike’s front end is planted. Get it in a corner with some weight bias up front and you know it’ll bury itself deep and securely in the apex. If you hold the brakes far into the corner, the front will fight your steering input but when you release them the ZXR drops in fast. This is the ultimate late braking 750, and has the brakes to suit. Some may prefer the lighter, quicker steering of the Yamaha, but there’s no ‘best’ here.

However, when the YZF was tankslapping the Kawasaki just twitched. A steering damper would be reassuring but the Kawasaki is as stable as the Honda in the rough. Kawasaki achieves this with greater weight and tauter, more adjustable suspension (shame about the threaded rear spring adjuster’s inconvenience, though) which gives plenty of feedback, some sore back and heaps of confidence. On a smooth road you stay locked to whichever line you want.

The price you pay is slower direction changes and more effort in riding hard in tight territory. The ZXR750 won’t dance under you as easily as the YZF.

Dunlop’s radials are superb. They give a mildly harsher ride but tend to hang in and communicate on a par with the Bridgestones on the YZF. You’ve got to be getting serious to touch down the ZXR’s footpegs but the Dunlops are willing.

The green bike has a clutch and gearbox combination not dissimilar to the Yamaha’s. Pillions get the added bonus of an excuse for a grabrail – it’s better than nothing, though. Switches rate on par but it takes a split-second longer to read the instruments on the Kawasaki.

The Yamaha’s style should have Kawasaki planning a leaner, nimbler bike to stay in the race in future years. But in 1993, the ZXR is one hell of a sports bike and comes together with motor, chassis and set-up to create all the right rewards for sporting riders.

Add the savings on purchase compared to the Yamaha and it could be that Yamaha won’t be worrying Kawasaki for a while yet.

Suzuki GSX-R750W

Suzuki was once the undisputed king of big four-stroke engines but that time seems to have passed, despite the watercooling update. But don’t let this put you off because the GSXR750W is a ton of fun by almost any standards.

This bike is one of the last of the peaky-powered bikes. While the Yamaha delights with its everywhere power delivery, the Suzuki gives a rush when you keep it above 9500 rpm. That’s when the cams come on song and the kilowatts kick hard. Play the clutch and gearbox – arguably the best of the lot – to keep the needles dancing and the GSX-R feels like the fastest bike in the world. And let’s face it, it’s worth sacrificing a few kilometres an hour for a bit of style.

Yet the Yamaha outclassed it in acceleration, everywhere, even in top-gear rollons where short gearing sees the Suzuki spinning at 6000 rpm at 115 km/h.

GSX-Rs have long had the edge in stability and bumpeating suspension. All these bikes should have steering dampers but only Suzuki has obliged and the difference is great. The suspension has the plush feel of long travel but spring and damping rates are well dialled in to firm up in time. It doesn’t give the feedback of the YZF750 but you can always trust this bike to keep its wits about it over appalling surfaces.

There’s also much more room to tune the suspension, thanks to compression adjusters front and rear which none of the competition has. Many argue such a range is overkill, but in a variety of uses this adjustability can prove invaluable.

We cursed the threaded rear spring adjuster. Our only real complaint, though, was that the rear damper was just beginning to fade after this bike’s 10,000-km-plus test life, taking the hard edge off its normally faultless high-speed cornering manners.

The same brakes have graced the GSX-R750 for at least four years now and they’re brilliant. You get very progressive, predictable power and plenty of it. It glides neatly into corners under brakes.

The Yamaha gets real sporting tyres. We had the new Michelin 89 rubber fitted to the Suzuki instead of the old 59s and, while the new tyres grip slightly better, wear more evenly and steer more neutrally, they’re still only sports-touring tyres. A change of rubber will transform the Suzi into the sports weapon it is.

Fairing protection isn’t as good as the Yamaha’s and the ride position is more hard edged. The footpegs could easily have been mounted lower by the factory to vastly improve comfort. As the other bikes show, who cares if folding ‘pegs touch down? The seat’s not bad and the ‘bars aren’t really buzzy at highway revs.

Overall, the Suzuki feels like a big, soft open-road sportster. It’s got its own enjoyable style but that style’s dating rapidly and is not cutting-edge any more. That doesn’t stop the GSX-R750 being the best bike if you want stability and predictability or peaky-powered fun.

Verdict

Yamaha’s YZF750R is an outstanding sports bike in many ways and the undisputed leader in overall 750cc engine performance. Steering is brilliant and chucking it into corners reaps more adrenalin-pumping rewards than on the other bikes.

The big Honda may accelerate a little harder and get delightfully light up front out of corners but the Yamaha rider will be having almost as much fun. On smooth roads a Kawasaki or Suzuki rider will be pushing harder to keep up with it and a Honda rider will probably only gain some ground when the road opens up slightly.

Between runs up mountain passes the Yamaha has a level of comfort which won’t have you aching after the first fuel stop. Its lights, switches, instruments and luggage carrying ability are as good as we’ve been given by the other makers and the finish is up there, too. If the pink doesn’t impress, there’s the black and purple option to consider.

Our only doubts surround its bumpy road stability, which was a real concern on our test, and whether the brakes on this bike can be fixed. As mentioned, the brakes should come good but we aren’t so confident about the stability. We shall see by next issue, hopefully.

And the competition? It’s got the engine and lightness to eat the Suzuki but not the price or the stability. However, value will depend on whether you want the latest technology or are happy to live with the one-generation-removed GSX-R, and whether you ride the rough back roads where the GSX-R comes into its own.

The Yamaha is also more sprightly than the Kawasaki but the difference, in the end, is relatively small and if the Yamaha doesn’t come good next month you can rest safely in the knowledge that the ZXR750 is the best 750cc sports bike here. Even if the Yamaha wasn’t left in some doubt for now, at $1410 less the Kawasaki is simply better value. It’s the best value (and, in fact, cheapest) big sportsbike on the market today.

Second on value among these bikes is the Honda CBR900RR. Our reigning Bike of the Year suffered some tall-poppies treatment from us, subconsciously. We realised this after everyone commented that each time they climbed back on the FireBlade they’d think, yeah, this Honda’s really good.

And it is. The blend of performance, handling, style, civility and extra touches makes it very hard to argue with. As it is, the CBR900RR is the best sports bike of the four.

Guido from AllMoto owned a 1992 CBR900RR — the original Fireblade, which won Two Wheels Bike of the Year — for a while and made this excellent vid review on the bike, which has now become highly collectable. Watch it here.

Yamaha YZF750R. Let’s try that again…

The last few houses receded in the mirrors and the speed limit opened up to 80 km/h. Out of town at last.

Time to seek thrills in the hills.

The 100 zone arrived around a corner and I wound on the throttle a little more. Not too much yet, just ease into it. After all, this is the refreshed Yamaha YZF750.

Yamaha took the sports bike back after our comparison and listened to our gripes about uncertainty and some juddering under brakes and a frightening lack of bumpy-road stability. Now the mechanics had finished and we were told everything was set up as it should be.

That involved a fair bit of work. Early on in the comparo we’d found a warped front disc and the other was showing signs of the onset of warpage. The front axle was slightly deformed, too. We’d tried heavier fork oil in it but when standard oil weight was 2.5W, the bike didn’t react well when we went to 5W and therefore doubled the damping effect. Both front discs were replaced with new, straight ones. We asked that the steering head bearings be checked, after a suspect adjustment during our testing. Suspension went back to standard.

Yamaha had criticised us for the suspension settings we’d finished up with. The front springs were wound up and the rear was fairly soft. Not a match, it seems.

However, our error in selecting heavier fork oil, combined with our finding that more preload had been desirable before the oil change, dictated our increased spring setting. At the rear, the lower preload settings were adequate for our riders and the damping had been set to match. At some stage, too, the rear wheel had been left out of alignment.

With all this apparently fixed, would Yamaha’s seemingly unconquerable 750 prove to be just that?

The engine is a powerhouse, the steering brilliant, the quality good. It had to persuade us that it could be trusted under brakes and that it could run with the rest on a fast, bumpy road.

Speed increased as the road unfolded. The brakes felt good but grabbed hard with each initial squeeze of the lever; speed washed off rapidly and there was never a need to commit deep into corners. Feedback was good.

Then the bumps started getting worse. A mess of tar caught the front as I braked into a corner and two things happened fast and frighteningly. First, the front jarred hard sideways and the back end launched briefly, too. At the same time, the airborne front wheel locked under brakes and gave a screech as it landed. Close to a fall but not quite.

I built up speed again. Trust it, I kept telling myself. But whenever I got the pace up a bit more, the handlebars would wiggle on the bumps. Slow down; build up the speed again; then wiggle, wiggle. Not harmless little shakes, but the sort which say, “If you push me, I’ll bite you back.” I pushed anyway. The YZF bit.

It’s not easy to see why the front’s like this. None of the Yamaha’s dimensions are as radical as the Honda CBR900RR’s, yet there’s no comparison between their bump handling abilities. Certainly the YZF’s front suspension leaves a bit to be desired in the damping department but overall the YZF feels more like a skittish little 250 two-stroke in the rough.

This bike has been aimed too closely to the racetrack. It really felt sharp at Phillip Island. On the road it is overbraked. The pair of six-pot calipers grab too hard at first and are too unforgiving if things go wrong. Worse than this, the YZF750 is no fun on a rough road. The rough roads I took this ride on were just typical Australian roads but I couldn’t safely get the Yamaha up to speed at all. Yamaha has done very well indeed with the rest of the bike. Now the factory needs to build more progression into the impressive six-pot brakes and put some stability into the front end.

By Mick Matheson. Two Wheels, August 1993. Testing by John Ewing, Mick Matheson, Anthony Seymour and Greg Reynolds. Pix by Helmut Mueller and Mick Matheson.