A Man and His Norton

It was in the wide cabin of an F100 Ford that it happened, while we were plugging across Melbourne with some trail bikes in the back.

A Norton cut between the traffic lanes, leaned across our nose and then left us its throaty, rumbling exhaust note as it accelerated through the slow-moving cars. The Norton insignia was regimentally displayed across the back of the rider’s jacket.

The youngster, 10, sitting next to me, remarked to his older companion (a 14-year-old subjunior MX rider who was testing a small bike for me that day), “Norton is only a small Japanese factory isn’t it?”

While the Ford lurched suddenly at my involuntary reaction, the older one replied, in what must be typical obtuse thinking of the young: “Why?”

“Because a kid at school was trying to tell me that Norton make only one bike, no trail bikes or minibikes (very important to 10-year-olds) or anything.”

“Yeah, well sort of. They made a hopeless scramble bike called AJS (another lurch) that Gary Adams (A-grade Victorian motocrosser) rode, but Nortons aren’t Japanese, the Brits make ’em.”

There was silence to this. And a sort of disbelieving, questioning look that showed the listener could hardly believe that bikes were built anywhere other than Japan.

I suddenly felt old. In the short space of 27 years, I have owned three Nortons and ridden many others along the way. But then, most of today’s riders were not even born when Norton was The Name for sleek, spirited mobility.

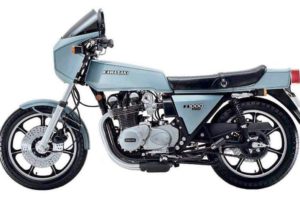

In 1974, the marque remains almost the last of the English legends to survive. And amid the hustle and multi-cylindered bustle that spells sophistication to a new market generation, Nortons retain the image and the capacity to offer a certain magic ride. A magic and mystique that comes from a heritage stretching back more than 50 years.

Seeing there appears to be much confusion about the history of bikes among youngsters, it might be an idea to have history lessons in the magazines. For instance, it was Norton which really initiated the “superbike” era and began the gradual proliferation of multis and powerful machines during the past six years.

It was back in 1968 when Norton first unveiled the Commando. The sleek styling and the updated Atlas engine combined with the revolutionary frame/engine mounting arrangement to offer the fastest production bike around at that time. Since then, the Norton has always been among the top of the superbike listings even though it lacks the flamboyance of extra cylinders and capacity.

While sales are not as high as one would expect, the Norton product deserves the legendary name and the “rather-fight-than-switch” attitude of its select band of owners. And after hearing that shattering conversation in the F100, I decided to take another look at a Norton and check the current 850 in an attempt to find the reason for it not selling the way the Japanese machines do.

The main outlet for Nortons in Victoria is the Peter Stevens network in Melbourne which sells around 10 a month. The 850 roadster was the bike tested. It had provided personal transport for almost a year for Peter Stevens Ringwood branch chief Vince Wilson.

One of the criteria for assessing whether to buy one particular machine or another should be the state of supply of spares. It can mean the difference between riding one summer or using your friends!

When picking up the 850 roadster I checked the spare parts at the Ringwood division. At this one centre alone, there were two complete frames, complete front and rear wheels, disc assemblies and calipers, two sets of all piston sizes, two complete crankshaft assemblies, tanks, forks and sliders, complete steering stems, headlights, and indeed everything to build a complete Commando from scratch. Try that at your local Japanese dealer and you will get an idea of what an incredibly good stock of spares Peter Stevens carries.

There is a decided degree of confidence in actually seeing all the parts sitting there rather than hearing the “we’ve got them on order” and the stock “the ship will be here next week” answers that have plagued some owners of Japanese machines.

The original Norton fastback Commando series success prompted the introduction of the 850 series, which was thought to be the answer to the bigger multis in the superbike sales race. But unfortunately there was a batch of trouble with the first 850s, especially the Interstate models. This was partly caused by an increased 10:1 compression ratio, which had some owners returning bikes to the shop with worn main bearings. It meant some bad things were said about the Nortons.

As a result, the factory went to a thicker aluminium head gasket to reduce the compression to 8.5:1. They also changed bearings and Nortons are now fitted with special German FAG bearings considered to be among the best in the world. The factory also changed the clutch plates (on a clutch that was renowned as the toughest in the business) and the plates are now sintered bronze and steel.

The remainder of the mechanicals have been proven over years of service and sensible use of the long stroke, torque-producing engine can result in an impressive lifespan for it. The engine is not Japanese. It is not a “revver”. No way. If riders rev it, the nature of the Norton is dissolved.

There are high-spinning engines around for those who want the feeling of a five-figure gear change every shift. These people should never ride a Norton!

Taking the Norton and comparing it on pure straight line performance with the current superbikes will prove nothing. Because while the superbikes have been developed all around with the super-slick extra cylinders, water cooling, and sophistication to catch the eye, Norton has been unobtrusively among the top all the time by sticking with a mixture of simplicity and an ancient design, combined with a remarkably sophisticated frame.

The isolastic rubber-mounted engine/swinging arm arrangement has now been proven to be lasting and efficient. The only thing that is required is regular checks on the clearance movement between the shims. Reshimming is simple and takes care of any undue movement that may lead to poor handling. Criticism of the engine’s rubber mounting has resulted from poor maintenance which lets things get very sloppy as the rubber bushes compact and the lateral movement exceeds safe tolerances.

However, one of the essential parts of being a Norton owner lies in the care and maintenance that an owner can and, in the normal course of riding, will undertake. The multis and such make owner tuning difficult and specialised.

Not so the Norton twin! And while it is not necessary to be constantly at it, a service and adequate tune is a couple of hours’ work once every couple of months. The best part of this owner involvement with Nortons is that there is certain to be a greater understanding of the machine and its specialised nature.

This special Norton attribute is revealed only on fast country roads. Roads with lots of turns, offcamber bends, decreasing-radius bends with long stretches that tax the suspension on the turns. In handling that type of road, the Norton 850 must still rate among the very best of the superbikes. In fact, there are few bikes of the size, dimensions and bulk of the 850 that can be flicked from one attitude upright and over for the next step of an S-turn as easily.

The fine roadholder forks are still among the best with good travel and excellent damping. This was demonstrated to me a few years ago when a car caused me to run up over a high gutter and through some light trees into a brick fence. The front wheel was shattered and I expected the worst from the forks. But nothing was needed. They were straight as ever and I rode that Commando another year without once worrying about the handling.

During this test I was zapping back from Hurstbridge, 64 km (40 miles) from Melbourne, along a road which is narrow, deepshouldered and cut to pieces along its edges. After hitting a completely hidden decreasing radius turn far too fast and cranking the bike over to a point well beyond its normal limit, the machine dramatically hit a collapsed edge in the bitumen. It was a hole about 250 mm (10 inches) deep!

The bike bucked like a motocrosser and leapt skywards. I felt sure there would be no traction a split second later. However, the Norton landed about halfway across the lane, straightened itself out, and we continued around the bend! Few other bikes would do that.

The 850 requires the normal procedure to start on cold mornings, and, after getting all that mass freed up and tickling the twin Amals, three kicks will result in a steady heavy thumping noise as the big twin fires up. It requires little warm-up for a steady idle (yes, believe it) and after that it was a one, or occasionally, two-kick affair provided all the steps are still taken in strict sequence.

The gearbox has four speeds, and on the test model the gearshift was on the right-hand side and has the opposite action to what has become the “normal”. And it works well.

Changes are not super fast but they are solid and dependable. And the gearbox is that way as well. It’s one item that should never worry owners during the time they have the bike.

The drum brake at the rear is still cable-actuated and still fairly inefficient. The hydraulic disc at the front is effective, but it requires far too much hand pressure, and there is still no adjustment available to set the lever for personal preference. The brake starts working as soon as you pull the lever and that means riders who like using only two fingers and have small hands (like me) are at a decided disadvantage. However, big fistfuls will slow the Norton dramatically, so I rate it as adequate, but with room for improvement in lever control design.

The clutch is a massive, extremely well-designed diaphragm spring unit that will never slip. It also freely disengages and has a long take-up action giving smooth, effortless starts. The pressure is very tiring after using the Norton around town for any length of time. Here again, one is confronted by the fact the Norton is a superbike, one of the lightest in the class but still heavy around the city.

I do not like the standard handlebars. The bike tested had the straight style. All mine have had shortened Triumph style ones giving a relaxed forward lean at high-speed cruising.

The seat has suffered since the first Commando. It is hard and uncomfortable on the roadster. A quick trip to an upholstery service and another inch of rubber will cure that. The long- distance tourer Interstate model has the much larger tank and a seat that is a decided improvement over the one on the Roadster.

The headlight has always been among the best and remains so although I favour the addition of one driving lamp. But those who travel fast at night will find the standard quartz halogen lighting excellent compared with anything else around other than the BMs.

The electrics are still Lucas, but they work. Levers and switches are still Lucas and are terrible. The chrome is excellent and the finish good. Expect the chrome to blue around the exhaust outlets (it always has), and expect the exhaust note to raise a few eyebrows (it always has), and also expect a lot of looks.

For the Norton still retains the air of the real big bike — far more so than bikes that, in reality, are bigger. The Norton also looks a true classical touring twin. If you remove the sidestand and re-attach the centre stand so it folds up higher, and then find you are still grinding things on corners, then you are really enjoying what the Norton is all about!

The triplex primary drive chain cover still leaks (it always has), but not excessively. With its oiler, the chain will last longer than on other superbikes and the 850 motor, with its truly enormous torque, will lug around in any gear you like. There is absolutely no point in revving an 850. With the redline at 6500 rpm you can concentrate on the midrange and by keeping the revs over 3000 you avoid any vibration (although I felt there was more in the 850 than the 750, but this impression was probably caused by running at moderate speeds, with the engine turning over at less than 3000 revs to keep within speed regulations).

This is not always easy. At 3000 revs you are exceeding the speed limit in most States!

The Norton marque is still among the elite in true point-to-point riding. It lacks the sheer power of the multis built for American highways, but the speed and acceleration figures are still right near the top. It suits our poor roads far better than most big bikes and outhandles them all.

In short, the Norton is classic. At $1725, it is also reasonable value.

You don’t own a Norton. You experience it. And at some stage in life, all big bike riders should try the Norton experience.

By Kel Wearne. Two Wheels, June 1975

Guido from AllMoto is a happy Commando owner and you can get the oil from him on the experience here.

And you can read Two Wheel’s roadtester Derek Pickard’s original evaluation of the 1973 Commando 850 here.