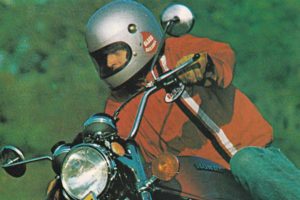

1998 Honda VFR800FI

Honda has a special place in its corporate heart for the VFR. This bike embodies so much of what Honda is: Innovative, but rather humble about it; conservative, but highly advanced; extremely capable, but aimed at the middle ground; very appealing, but somewhat bland.

It is also a little confused, in that it boasts all the development from Honda’s Superbike racers but could never hope to get serious on the track. It is a fantastic bike that tries to be all things to most motorcyclists – and very nearly is.

Honda tries really hard with the VFR, too, and shows it off as, in its own words, a rolling showcase of the company’s finest motorcycle technology. But only as far as real-world mass-production is concerned, of course, or it’d have oval pistons, variable valve timing and heaps more stuff – and cost more than a hundred grand. Even so, technically speaking, the VFR is an exciting machine.

The 1998 model’s headlights and sharper styling steal attention from the two key changes over the previous model – a new engine and new frame. The VFR is now a fuel-injected 800, not a carburetted 750. Its frame now doesn’t have a swingarm pivot.

Honda ditched the old engine and brought in a bored and stroked version of the one built for the 1994 RC45. This engine has the cam-driven gears (remember there’s no cam-chains in the VFR) beside, rather than between, each pair of cylinders, which negates the need for one of the four crankshaft journals and therefore enables the engineers to build the whole thing 15mm narrower. The move to three journals also brings a small loss in friction and weight.

Cylinder sleeves made from sintered aluminium powder with ceramics and graphite, just like the ones from the RC45 and the 1998 FireBlade, save two kilos as well as giving better heat dispersal qualities. The other bikes’ LUB-Coat solid lubricant has found its way onto the VFR’s slipper-type pistons as well.

Like the RC45, the VFR800 is fuel injected by the same PGM-FI system, but with fewer parts to simplify things. The system is not so advanced that it calculates its own cold-start mixture, and so still needs the “choke” lever on the left handlebar. The electronic engine management includes an innovative dual-intake airbox with a solenoid that closes off one intake during low-speed running to ensure efficiency is maintained. As revs rise, and the engine demands more airflow, the second duct is opened.

Australia doesn’t get the catalyser-equipped model destined for some European countries, but our VFR800 still comes with a new version of Honda’s air-injection system which brings fresh air into the exhaust port during the exhaust stroke so that the gases are burned more completely and nasty pollutants are reduced significantly. The muffler is stainless steel.

The VFR takes a lead from the VTR1000 twin by carrying its two radiators sideways next to the engine. Several benefits of the design include having cooler air stream in over the engine itself, easier front cylinder access for maintenance, and being able to shorten the wheelbase while keeping weight forward. The final point is negated in reality because the crankshaft is actually 15mm further away from the steering head, and seven millimetres further from the front tyre contact patch, than on the last model, possibly because of the (unquoted) length of the new engine; all the real shortening of the wheelbase has occurred behind the crankshaft.

It becomes critical to run the bike with the fairing in place, though, because the cowling shape directs air through the radiators; without the fairing, air would stream past them.

The new frame also takes its cue from the VTR. It is the same pivotless set-up, with the swingarm mounting to the engine cases, and it has saved 3.5kg. The spars have been beefed up; they are still triple-box section, but now almost 50 per cent deeper and with thicker walls. At the back of the frame, a crossover piece closes the frame into a loop and gives the rear suspension a top mount. The seat frame is bolted on.

The changes endow the new bike with a lighter, sportier feel than ever, and noticeably more responsive handling. The VFR has always been one of the easiest bikes to ride well and ride quickly, even when the road begins to fall apart. That’s even more the case now.

You don’t pitch a VFR into a corner. You lean it in. The wheelbase is 30mm shorter and the steering is half a degree steeper, but its trail of 95mm and its 1440mm wheelbase, even though they are quick, are just outside sporting dimensions. It has the tallish, slightly skinny feel of a sports-tourer – like the Ducati ST2 or BMW R1100RS – and plush suspension settings which cope well on the road but don’t like to be hurried. So you lean it in and enjoy the superbly balanced feel of the chassis.

The centre of gravity seems to be somewhere close to your own, but a lot lower, and the control this gives you is excellent. Steering is quite neutral.

But when you hustle the Honda it shows its softer nature and becomes unsettled. The slight doughiness means there’s no hiding the weight- 208kg dry – whereas tauter bikes like the Ducati ST2 get away with it.

On a dodgy road where grip is never guaranteed and the twisting tar is rough, narrow and unpainted, the VFR is actually quicker and more surefooted than a sportsbike. Its roadholding and stability are good and reliable. However, the 120mm of wheel travel at either end isn’t especially generous, and its rough-road composure falls apart at lower thresholds than the Ducati and BMW.

It also gets to a point where the singlesided Pro-Arm suspension reacts like it always has, and overcomes the spring/damper’s abilities to control the weight. Honda claims for the 1998 VFR that the Pro-Arm is a lightweight item, and it is certainly 30mm shorter than before, but it feels like it contributes greatly to unsprung weight, and corrugations and other series of bumps bring this out. In fairness, some big bikes with normal swingarms suffer the same way, and the R1100RS, with its Paralever single-sided swingarm, does it as well.

The brakes are right in tune with the chassis. The VFR has never worn top-notch anchors, but this time around it has the latest version of Honda’s Dual Combined Braking System (DCBS), which links front and rear brakes through a third master cylinder. When one brake is applied, and the front end dives, the third cylinder is activated and this engages the other brake. Each caliper is fitted with an extra piston, operated by the third cylinder.

Isolate the front and rear brakes and you have the same two-piston calipers either end which aren’t in the league of four-pot items. But, in fact, the calipers are threepiston units, and the braking pressure is thus a little greater under full braking. The original CBS, fitted to the CBR1000F several years ago, was deservedly criticised for its poor behaviour in certain circumstance, like in U-turns when it tried to unbalance you. CBS has developed to where now, with the addition of a delay valve and use of the proportional control valve, you would hardly know the system was there at all.

The delay valve is set up to smooth front brake pressure when you are only using the foot pedal and want gentle, controlled braking. It does this by first sending pressure to the front left brake only (as well as the rear brake, of course), and then the right brake as pressure is increased on the pedal. It brings more control and safety to low-grip situations, where too much pressure on the front brake could lock it, like going down gravel hills. Experimenting showed it is always the rear brake that locks first when the foot pedal is used. However, the pedal lacks feel and needs a very firm stomp to get much action at all.

If using the brakes is more of a joy, getting up to speed is twice the fun. The engine is a gem – and that’s a cliche that’s been applied to the 750 V-four ever since it first came out in 1982 as the VF750S. It is not strictly an 800cc engine, though, at 781 cc. The extra cubes, and the ditching of its self-applied 74kW power limit, have given the thing even more life. A fat curve of power from idle to 81kW propels the VFR800 in a way few other bikes can match on the road. Its real-world performance is excellent, far more so than the sum of its onpaper figures.

Gearing is taller than the 750’s, with the dials showing 4000rpm equates to 94km/h instead of 86 as it was. But that’s still on the low side for a bike this big. This helps its top-gear response at highway speeds, and there’s rarely any need to knock the VFR down a gear to overtake. Just wind it on and surge past. Relaxed touring at a fast, loping gait is the VFR’s forte.

The temptation to use the top end is always there, though, because the performance is good. Releasing its grip on the 74kW limit hasn’t unleashed a whirlwind of power up near 90kW, which is where the sporting 750s are, but 81kW in a bike not much over 200kg is nothing to get blase about. And it is a very usable top-end, partly because the power isn’t astronomical but mainly because the build-up through the rev range is so predictably smooth.

The new engine vibrates less than the 750. Its 180-degree crankshaft arrangement brings pulsing vibration that emphasises the V configuration and adds character, not annoyance. The vibes increase as the revs rise, though, and by 7000rpm you can feel them tingling right through the bike.

Fuel injection has made some Japanese bikes, with their light flywheel effect, too sharp for comfort on the throttle. The VFR800FI just manages to avoid this. Its injection is definitely responsive to every throttle movement but the reaction is softened just enough to take the jerkiness out of it. It no doubt contributes to improved economy, with as little as 4.8L/100km used on one freeway run at an average of more than 130km/h.

The six-speed gearbox is typical Honda, with a very definite action and audible clicks on many changes. Missed gears are rare, and neutral is easy to find.

The new design includes a roomier riding position, with a longer seat and more leg room. It puts less pressure on your wrists and is genuinely comfortable for long distances. The fairing pours just the right amount of air onto your body at most speeds and is big enough to tuck behind without straining at high speeds.

But the new Honda is not without its faults. The VFR is built for comfort , but the new fairing leaks copious quantities of hot air from under the tank and it broils your thighs and crotch. Probably great on cold winter nights but warm weather cruising leads to a damp, sweaty groin and cloying leather pants. Another time and place and it could be fun…but not on a VFR.

The second frustration is a result of the gears driving the camshafts. Some gear whine is inevitable, but at 4000-4500rpm the 800 engine screams like a banshee. Not only is it loud enough to piss you off from the saddle, but it can be heard by everyone around you too. Worst of all, it happens at the most comfortable revs for tooling around town.

Exhaust notes are a scientific art these days, and bike makers strive to get good sound within legal limits. The VFR800 has a superb and surprisingly loud V-four growl that’s music to the ears. Unfortunately it is only bystanders who hear it as you accelerate away…

The details are excellent. Six tie-points let you secure a load to the back seat. The pillion has solid grab handles which bolt into place; or you can use the solo seat cowl when alone. The clutch and brake levers are both adjustable, both stands are well designed, and the comprehensive dash displays include an LED readout of ambient air temperature. The dash is attractive and clear, with an unusual serif typeface on the dials.

There was a rattle in the fairing panels by the end of the test, and the rear panel on the right was rubbing against the tail light. The fuel tank pivots up, a la Ducati, for easier maintenance, but services are 12,000km apart anyway. Valves only need checking every 24,000km, although whether it’s wise to leave the oil in for the scheduled 12,000km is debatable. Some would want to do two, three or even four oil changes in that distance, just to be sure.

The VFR, as a fuel-injected 800, remains one of the best motorcycles on the market. But that market is finally getting more sophisticated, too, and includes not only the BMW R 1100 RS but now the Ducati ST2 as well, which, despite quality niggles and a modest power output, sets a new benchmark for sports-tourers.

The Honda would be a much better bike if it too had an integrated luggage system to round off the package. And the Ducati shows how much more sporting a sports-tourer can be, without loss of comfort, if the running gear is given as much thought as the rest of the bike. Honda has the ability to make the VFR the best bar none, but it has some work to do to get there. It should also cure the heat coming from the fairing and the gear whine.

The 1998 VFR800FI leads the class in other ways. It has the best engine performance and a high standard of quality. Longevity and hassle-free ownership are sure things, backed by the long warranty. The integrated brakes are a worthwhile inclusion and suit the nature of the machine. And at $15,000, just $1000 more than the model it replaces and makes so many improvements on, it is exceptional value.

By Mick Matheson. Two Wheels, April, 1998.