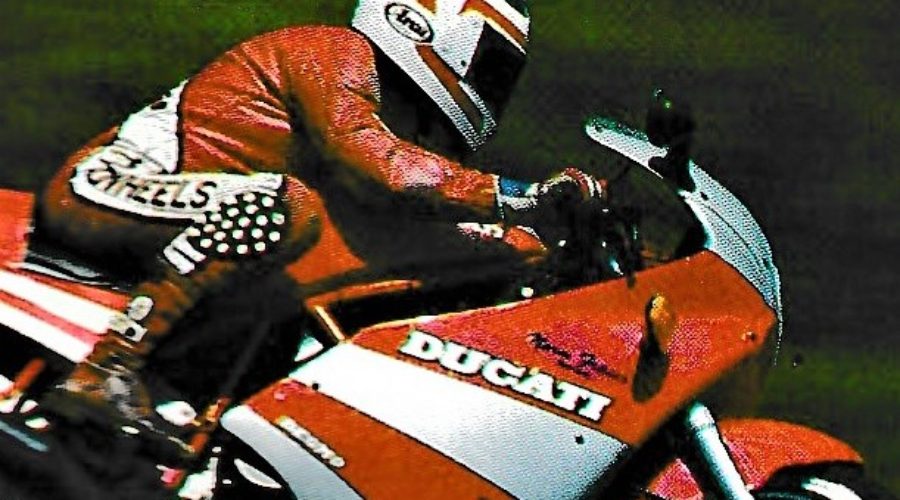

1989 Ducati 750 Sport

The thought of testing Ducati’s new 750 Sport had chief roadtester Geoff Seddon weak at the knees in anticipation. Did the name Sport herald a new King? Would this be the bike to rumble the Ducati faithful? Here’s Seddo’s report, superbly backed by Peter Beattie’s photography.

It was a bit like rushing home to tell the folks that you’d been accepted at a fitter’s course at Tech, only to find that your big brother had just been awarded his Masters in Mechanical Engineering.

The new Ducati 750 Sport was released in the shadow of the mighty 851 Strada, certainly the most exciting new Ducati to be released in 15 years and one of the landmark bikes of the Eighties, period.

It’s difficult to think of a harder act for the Sport to follow.

All the early reports from overseas raved about the performance of the big eight-valver, often with an “Oh yeah, by the way…” reference to the 750.

Slowly, gradually, a picture emerged of the Sport as a cross between a Paso and an F1 and we started to take a bit more notice.

By the time the new bikes arrived in Australia, we’d half convinced ourselves that the 851 would be an expensive, unrideable, temperamental brute only suitable for the racetrack while the 750 Sport sounded kind of good – not too dear and if it looked and ran like an Fl with the comfort and civility of a Paso, then we could be on to a winner.

Of course, the 851 turned out to be much, much more. It was by far the best handling Duke ever but it was the motor that took us all by surprise. I don’t think anyone expected the 851 Ducati to be as quick as it was. Twins just didn’t go like that.

I stepped off the 851 and hopped straight on the 750 Sport. Again, it was like celebrating your birthday on Boxing Day, or finding out that your parents have just bought you a CX500 while you’ve been out test riding a new GSXR1100. By the end of the test, I had very mixed feelings about the 750 Sport. It was a great little bike, but …

Life returned to some semblance of normality. Test bikes came and went, but with the procession came a realisation that lots and lots of bikes paled in direct comparison to the 851. Perhaps I’d been a bit harsh on the 750 Sport. I wondered if I could get it back for a second helping.

I’m glad I did. Some of my earlier misgivings remained, but my enthusiasm for the bike grew and it was a lot harder to give it back the second time. The bike was a Ducati to its bootstraps, albeit a Ducati of the old school, but its name took on a delicious irony.

The first Ducati 750 Sport was released in 1972. A tuned (42 kW), cafe racing version of the newly released GT750, it established the 90 degree V-twin as synonymous with Ducati sports motorcycles, a situation that exists today and is likely to remain for a very long time. It also became the mother of a whole generation of ‘bevel gear’ sports Ducatis, culminating in the 1000 cc Mike Hailwood Replica.

If the first 750 Sport was the first of a great line, then the new 750 Sport represents the last of an equally prestigious family. The Pantah, first released in 1979 in 500 form, offered significant engineering advantages and a previously unheard of dollop of reliability compared with the big twins.

The motor grew to 600 cc, then 650 briefly, before forming the platform for the crude but infinitely satisfying Fl and the svelte 750 Paso. Its last resting place is the 750 Sport. The belt-drive, SOHC, air-cooled motor is suddenly old, making hard work of modern noise regulations and simply not able to be tuned to give the performance a lot of riders appear to want these days.

Its 54 kW at 8500 rpm isn’t much of a power figure alongside the 79 kW of the Kawasaki ZXR750 or the claimed 85 kW of a GSX-R750. It’s not so much a matter of a lower top speed, because anyone who reckons a top speed of 200 km/h is limiting is probably a fool or a liar and arguably both. However it does lack the punch of a well-ridden Japanese sports bike out of the corners and along short straights and so on.

Yet this won’t prevent the odd 750 Sport collecting its fair share of scalps, particularly by enthusiasts who know both their bikes and their roads well. Woe betide the ZXR rider who takes on Anthony Seymour along the tighter sections of the Princes Highway without doing his homework first.

I remember my inaugural strop up the Old Pacific Highway. The bike was easy to ride fast and I found myself working the 748 cc, four valve V-twin hard, getting on the gas early out of corners, giving it a big fistful and watching the tacho like a hawk. Hit nine, upshift, hit nine again, upshift, gas on, gas off, back a gear, back a gear, line it up, take the apex, steady, gas on hard and do it all again. It was physically exhausting but wonderfully enjoyable, riding a thoroughbred sportster to something approaching its potential. Handling and steering felt spot on at those speeds.

An early model GSX-R1100 came from nowhere and took me cleanly along a short straight. The rider was smooth, as you need to be on bikes like that on tight roads, and hit the next corner with just enough brakes and a lot of style.

Pluck a Duck

We were approaching a slower, trickier section of the road and it was obvious the bloke knew the Highway as well as I did. But the big Suzuki was slow to react in this environment and I had the little Duke closing the gap. Then the road opened up a little and the advantage was lost.

In the spirit of true Sunday scratchers everywhere, the Suzuki rider resisted the urge to scoot off on the longer straights, using just enough power to keep a safe distance in front of the pesky twin on his tail. I responded by pushing the Duke a little harder into corners.

The 750 Sport steers like a Paso, unusual at first but bloody terrific once you get used to it – at which point the bike got a little less tidy, wanting for a touch firmer damping on the rear monoshock under the extra strain. I was now getting back in behind the fairing on the straights, braking later and getting into some serious acrobatics on the sweepers while all the time gunning the engine for all it was worth.

Which frankly, is heaps. While neither of us was doing anything desperate, and accepting the fact that the GSX-R1100 could probably have pressed an unassailable advantage if the rider chose to, I had had an absolute ball. While the Suzuki rider might have been in fast/cruise mode, for all intents and purposes, I was racing!

In this environment, the 750 Sport is deserving of its 1970s namesake and certainly one of the most entertaining bikes I’ve ridden in a while. The tyres are fantastic if spectacularly expensive (try around $225 for a new tyre every five or six thousand km), the brakes offer sufficient power with above-average feel and most of the suspension quirks can be tuned out of the bike with a bit of patience. The frame is as good as you’d expect from Ducati, but whereas it might owe its heritage to the F1, the ride is a little less harsh.

Rebound damping adjustment on the rear Marzocchi shock is near as you’ll ever get to truly infinite. The softest setting is zero damping – with no air (which controls compression damping) the bike will dance up and down on the spring for ages, while at its firmest setting it takes on the characteristics of a pneumatic strut. With something approaching sixty settings in between, finding the right combination felt like it was going to take forever. Thankfully, access for damping adjustment is fairly straightforward, though spring preload adjustment (via a continuous thread arrangement) requires removal of the tank.

Steering the Fat

Up front it’s a matter of being satisfied with what you’re given. Short of experimenting with different grades of fork oil, and different springs if you’re really keen, the twin 40 mm Marzocchi forks are not adjustable. I found they had a tendency to bounce off the bumps a bit – disconcerting on a light bike (195 kg dry) with a fat 16-inch front wheel and no steering damper.

Mind you, I survived the test period without incurring a single tank slapper, though speeds were down on unfamiliar roads below what they otherwise might have been. Like the Paso and the 851, the 750 really works the front tyre hard, but whereas the trick M1R Marzocchis on the other bikes inspire an almost fanatical confidence in the ability of the front end to do no wrong, the cheaper units on the Sport do not. On smooth surfaces, or on roads that you know well (where you can steer around the bumpier bits), the forks work well enough with good feedback and there’s no problem.

Twin opposed-piston Brembos have been around since Moses was a boy and show their age in less than outstanding braking power. However, any disadvantage is largely compensated by superior brake and suspension feedback and arguably the best tyres money can buy. While the power of the 851’s four spot calipers would be nice they weren’t really missed given the slower engine and less sophisticated suspension of the Sport.

The motor is derived from the Paso, performs like the Paso and sounds like one too. It is not as smooth, however, shaking like an Fl at higher revs when you give it a real handful. The reason probably lies in the frame. The Paso’s is an ugly, cobbly bloody thing tucked away behind acres of red fibreglass, but is good at absorbing secondary vibration from the 90 degree twin. The Sport’s is more your typical Italian work of art, great to look at and nice and rigid, but more prone to pass on the vibes to the rider. Vibration is not obtrusive, more a constant reminder that it’s a twin cylinder four stroke working hard down there, which I find kind of nice.

A limitation of the Pantah heritage is the five speed gearbox with overall gearing a bit shorter than you might expect from a 750 cc twin. Five thousand revs in top equates to an indicated speed of around 120 km/h. Bevel SS Dukes used to pull around 150 km/h on standard gearing at the same revs. With the motor making serious horsepower from under 4000 rpm, this gearing results in strong top gear acceleration at touring speeds at the expense of a less relaxed feel. Clutch and gearbox action caused no complaints.

The Sport shares the Paso’s much-maligned twin throat 44 DCNF Weber carburettor. Unfortunately, the test bike also shared the Paso’s off-idle carburation flat spot but like the Paso this only manifests itself in city riding and is not such a big deal once you adjust to it. The bike carburates cleanly from 3000 rpm right through to the 9000 rpm redline, with that lovely flat torque curve which has become a Ducati trademark.

Alimony

Engine maintenance is easier than on older Ducati engines due to a revised shimming arrangement for valve adjustment, though accessibility to many components is more fiddly. Anthony Seymour gave us the lowdown last issue on what’s involved. Overall, the motor should prove enjoyable to live with, especially for riders out there who like to tinker with their bikes as well as ride them. A well-maintained example should last for a long time. Alternatively the Sport would make a great hot rodder’s special for those who enjoy that sort of thing, with hot-up parts galore available for this long running motor.

I can report too that much like the older Ducatis, a minor get off is not necessarily terminal to the bank balance. A twit at a Ulysses Club ride day put the Sport down pretty heavily on some wet grass. The Sport needed a new blinker and a minor repair to the fairing. Unfortunately, the petrol tank was also damaged, developing a slow leak which cut short our first look at the bike.

Again, it was repaired inexpensively.

In the flesh the bike is very small for a modern 750 and a good looker to boot. Traditionalists will approve of the styling that allows at least a peek at the motor, though I had to laugh at the nickname coined for the Sport by some of the more rabid Ducati big twin fetishists out there. They call the new Sport the ‘Lolly Pop’. Luddites!

The paintwork is of a high standard and the bike sits very low on the road courtesy of the trick Oscam 16 inch wheels and enormous Pirelli radials – a 130/60 ZR16 on the front and a 160/60 ZR16 on the back! The bike’s lowness contributes to the high of riding the bike hard through a corner by getting you that much closer to the tarmac, a fantastic feeling. The payoff is the typical bane of the sports bike (not enough space between seat and footpegs) on an otherwise relatively comfortable bike. The seat’s good enough, with the lean to the clip ons just right. Pillion accommodation, I’m sorry to say, is pretty much par for the course for this type of bike.

Ducati is moving with the times with things like rows of bright idiot lights (neutral, oil pressure, battery charge, headlights, high beam and fuel) and a steering lock incorporated in the ignition switch, but not all progress is good. The spring-loaded sidestand could catch out the unwary (take the weight off it for a moment and it retracts), there is no fuel gauge or reserve tap, just a low fuel warning light) and the mirrors, while better than the Paso, aren’t much chop. Lord knows, if there’s one thing the sporting rider needs in 1989 it’s good rear vision mirrors.

Tools are under the rear cowling (the battery’s up the front, under the steering head) but you’ll need an allen key to get the solo seat attachment off before you can get the seat off to get to the tools – where you’ll find the allen key …

What hope have we got, even the Italians are doing it.

But of course such things are minor if you’re hankering after a 750 Sport. As the last of a great line of air-cooled Vtwins, you’d almost expect the bike to have its fair share of idiosyncrasies and the Sport does not disappoint. The around town carbie hiccups are compensated for by the bike’s position as the best city lane-splitter I’ve ever ridden and its lack of outright horsepower is forgotten when it’s just you, your Duke and an empty winding road to share.

Pushing any well-sorted V-twin Ducati hard is for many individuals, one of motorcycling’s greatest pleasures and the new 750 Sport is every inch a Ducati.

Recently factory moves to re-establish Ducati as a volume mover outside of Italy have resulted in some dramatic price reductions for the 851 Strada and the 750 and 906 Pasos. Obviously, Sports must have been selling well around the world because their price was discounted least and we now face the situation where the Sport, previously the entry level Ducati in marketing terms, is now quite a bit dearer than the 750 Paso and much the same money as a 906. I reckon the Paso is the better bike to ride courtesy of its M1R forks. I also think it’s the better looker, though on that score I’m undoubtedly in the minority.

Whatever, I can’t see any buyer being too disappointed with his or her new toy. While it has nothing like the outright power of the Japanese 750 fours, the Pantah engine has always been and remains a very satisfying motor to own and ride, and the rest of the bike is well matched to its performance. It makes all the right noises too.

The saddest part is that bikes like this are getting pretty thin on the ground these days. We’re witnessing the passing of an era. If you’re looking for a permanent reminder of what sports motorcycles were like before the onslaught wrought by the GSX-R Suzuki and its ilk, then Ducati’s 750 Sport could just be the go.

By Geoff Seddon. Two Wheels, August 1989