1986 Laverda SFC1000

Lining up bikes to test in Two Wheels has always been an aspect of the job which has its fair share of coincidences and twists of fate. As a rule, the more desirable the bike, the harder it is to get hold of, because every other bugger wants a run on it too. Slow sellers are never a problem.

“Gidday, Two Wheels here. We’d like to test your latest slow seller.” “Sure, how many would you like? When do we want it back? Keep it as long as you want, no worries.”

It looked like we had well and truly struck out with Laverda’s SFC 1000. Only 20 have been imported, and distributor Max Eade wasn’t about to put on a demo when his books were full of orders. So, no go.

Not quite. We wrote to Club Laverda NSW asking if any of its members had an SFC which we would borrow for a couple of days. A letter came back, informing us politely that, yes, a few members own SFCs but, no, they ain’t about to lend ’em to anybody. Oh well, it was worth a try.

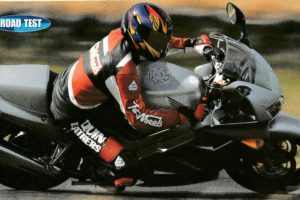

Soon after this, I received a call from a gentleman by the name of Mark Lennon. In what I can only assume was a sudden burst of generosity following his election to the position of Club Laverda Prez, he offered his SFC and we were on our way.

The SFC has several features in common with the Corsa. Firstly, the engine is the same dohc air cooled triple with the 120 degree crank phase first used in the RGS. Performance modifications to the Corsa/SFC version of the motor include a ported (tapered inlet, straight exhaust) and flowed head, forged pistons (giving a higher compression ratio of 10.5:1, up from 9.0:1), larger inlet valves (40.6 mm, up from 39.5), smaller exhaust valves (34.0 mm, down from 35.0) and 118 main jets (replacing the RGS’ 108s) in the 32 mm Dell’Ortos.

The SFC also gets the Corsa’s Goldline Brembo brakes, double cradle tubular steel frame with rubber engine mounts, and switchgear/electric assemblies.

Light up

However it is different in many respects, and the main reason for this is that the factory realized the need to shed plenty of the Corsa’s hefty 244 kilos for the sportier SFC. No dry weight figure is available for the SFC, but it’s safe to assume that modifications such as the bare bones fibreglass fairing with no trimmings, new wheels, less extensive body panelling, lightweight Marzocchi MIR forks, a rectangular section alloy swingarm and the spartan alloy footrest/lever/bracket assemblies have resulted in a dry weight figure of around the 215-220 kg mark.

The SFC is still a heavy machine, although Jota riders will tell you that it feels like a 250 compared to their bikes, and given that it is of more sporting intent than the Corsa the result is noticeable on the road in the form of more responsive steering, slightly better performance, and a generally more nimble package.

Engine-wise, the big 981 cm3 triple is an excellent sports-touring effort. Low rpm power is weak, accentuated under 3000 rpm in the test bike’s case by very jerky running. The ignition pickups (one for each cylinder) are arranged around the left end of the crankshaft, and unless the gaps are spot on the bike lurches badly just off idle. The magnetic force between the crank and the pickups is sufficient to narrow the gaps over time, and it’s simply a case of trial and error until you get it right. Still, with three pickups/CD1 boxes and coils, chances are you won’t be stuck beside the road with ignition failure.

Snapping the throttle open too quickly with less than 3000 revs up also caused the test bike’s engine to cough and splutter, but this could probably be eliminated by experimenting with jetting, which seemed to have been adversely affected down low by the accessory three-into-one fitted.

Upwards of 3000 rpm (80 km/h in fifth) this roughness disappears and is replaced by a typical triple grumble; it’s difficult to describe, but I guess you could say that the vibration frequency lies somewhere between that of a V-twin and an in-line four. It’s certainly not buzzy enough to send the hands, feet and bum to sleep, and the three rubber mounts isolate the rider reasonably well, improving as revs climb. At no stage can you call the SFC silky smooth, but its vibrations are less hard to live with than most fours’.

Power from 3500 rpm (100 km/h in fifth) is sufficient to leave most bikes behind, apart from the likes of the FJ1200, the K series BMWs and big GSX Suzukis. The test bike’s motor was still fairly tight at first (3300 km on the clock) and wasn’t particularly free revving, but responsiveness was exceptional. There aren’t really any peaks or troughs in the delivery as redline approaches, apart from a slightly stronger kick in the backside between 5500 and 8000 rpm, and this makes the Laverda all the more impressive. The old cliche “pour on the power” definitely applies here.

While responsiveness is one of the motor’s strong points, at no stage is it such that more than a moderate amount of caution is required when driving out of corners. In addition, the generous midrange means that even for tight 35 km/h bends, third is as low as you need to go, and with the standard Pirelli MT28 Phantom on the rear, the big Laverda’s grunt can be used to full advantage. It’s not wise to roll the throttle on too quickly when exiting tight bends, but you can be more heavy-handed than most sports bikes allow because the power doesn’t come on too suddenly and you don’t need a zillion revs to get at it.

As far as comparing the Laverda with other European bikes goes, it packs more punch than any of them at a rated 70.8 kW. The K series BMs and Guzzi’s 1000 Le Mans are in the mid-sixties, while the Ducati 1000 Hailwood Replica produces just under 57.

On the road there’s some similarity between the Laverda and the BMW Ks. Both are at their best over long stretches of open country where 140 km/h plus speeds can be maintained, and, like the BMWs, the SFC makes short work of long distances. At 140 km/h it’s running around 5000 rpm, while increasing speeds to the 160 region adds only a further 750 to the tacho.

Top gear punch from 100 km/h is adequate for all but the hastiest overtaking situations, and the motor’s unstressed nature has a similar effect on the rider as the kilometres build up. The Laverda is one of the few bikes that tall (over six feet) riders don’t have to squeeze some part of their anatomy into, and the half and half sports/touring riding position, together with the reasonably gentle seat (which is good for a tankful before the bum cries enough) gives the SFC owner a bike with plenty of ability as a high speed, long distance tourer.

It does have its limitations in this area, notably a range of only 300 km even when taking it easy (I ran out of juice after a 200 km ride in the rain and a couple of days hacking around Sydney), macho-man throttle springs, which you could get used to or replace, and few ocky strap attachment points for carrying gear.

At night things are dim on all fronts, with the headlight only being good for 110-120 km/h riding and the lights on the Smiths instruments so useless as to be non-existent. The latest model has white-faced Veglia dials, and hopefully these are a bit better.

Uno springo

The SFC’s suspension at both ends features the latest from the Marzocchi range. At the front, 41.7 mm MIR forks are fitted, and in design they are unconventional to say the least. Instead of a spring in each fork, the MIRs have only one, in the right leg, together with a four-position external rebound damping adjuster. The left leg contains a one-way compression damping valve and a hydraulic device which prevents bottoming. Unlinked air caps are fitted, but the MIRs aren’t designed to use air for any purpose other than minor adjustments for different rider/passenger loads.

Marzocchi claims that one spring is sufficient as long as measures are taken to eliminate stiction. To this end, the MIRs have highly polished staunchions and teflon bushes fitted to the aluminium alloy sliders, while rigidity is maintained with a brace.

In practice, settings one and two on the rebound damping adjuster caused the forks to top out occasionally after large bumps, but otherwise they worked well enough, offering better compliance than the less exotic Marzocchi front ends fitted to the likes of big Ducatis, yet being sufficiently firm, even with only one spring, to not go close to bottoming out even on particularly rough pieces of road. At no stage did the front end feel strange due to the separate spring/damping functions being carried out in different legs, but even a small amount of air rendered the forks harsh and uncomfortable.

Front end stability was first class: no bump steer, no twitches, nothing.

At the rear is a pair of Marzocchi Symbol spring/damper units. These are similar to the alloy-bodied AG Stradas, but have a larger diameter steel body. This allows for greater oil capacity and a larger damper piston/washers, the main benefit of which is claimed to be a finer degree of control over small wheel movements. A four-position external rebound damping adjuster is located at the base of the air chamber, which now has a floating piston, replacing the Strada’s neoprene bladder, separating the air from the damping fluid, due to the fact that it carries its air at a pressure of 90 psi rather than the Strada’s 28 psi.

These are Marzocchi’s top of the line road shocks, and their performance is measurably better than the Stradas’. There’s slightly more travel available for a start, and on the third spring preload position out of five compliance in all situations was excellent. They didn’t bottom out at any stage and it was only a huge bump that lifted self from the seat. On rebound damping setting two the wheel stayed glued to the road and the damping was sufficiently well-matched to the springs to the extent that no wallowing, weaving or other antics even looked like appearing. These are about as good a pair of spring/damper units as you can get, and the range of adjustments offered (given that I only used the middle settings solo) should mean that they’ll still perform as well with a passenger and gear on board.

Top-notch suspension front and rear gives the Laverda a head start when it comes to precise, stable roadholding, and its steering characteristics fit this mould. The 18-inch front wheel and 1520 mm wheelbase, together with slow steering geometry, make it a bike in the classic European style. It won’t steer itself for you, but then it won’t go where you don’t want it to either. It is quite a top-heavy beast, but once this is accustomed to it’s relatively easy to ride even in tight terrain, where the overall weight reduction measures show through. Most quick steering Japanese bikes will see it off in these conditions, but once you’re into the 55 km/h and above corners the SFC’s stability will pay dividends.

The only handling quirk exhibited by the SFC (and it’s one common to Laverdas) is a tendency for the rear end to wriggle around a bit at speed on a trailing throttle. No-one has yet come up with an explanation for this, but theories range from the top-heaviness of the bike to the relatively pliable alloy wheels. Different tyres don’t seem to have much of an effect, and in any case it is not severe enough to be a worry or a hindrance except under racing conditions.

The brakes are one of the most outstanding items on the bike. The twin Goldline Brembos (twin piston fixed magnesium alloy calipers, fully floating 300 mm discs) at the front are equal to the four-piston Suzuki GSX-R devices in all respects, except for panic stops where a little more lever pressure is needed. At the rear (an underslung caliper, with single fixed rotor) a fair stomp is necessary, but the latest SFCs have a slightly larger piston in the master cylinder, so the same result can be achieved with less effort. Still, with the front brakes as good as they are, this is probably unnecessary.

The wet, multiplate hydraulic clutch (driven by two single row primary chains), is pleasantly light and easy to use. It engages positively but not in the snatchy fashion common to many other hydraulic units.

The five-speed ‘box engages each cog without crunching or hesitation, but is notchy and “wooden” in feel. Drivetrain freeplay is minimal, except when the previously-mentioned sub-3000 rpm jerkiness affects it.

Ancilliaries on the SFC are generally poor by today’s standards. Lights and instruments, as mentioned previously, aren’t up to scratch. The Smiths tacho doesn’t have a redline, but as I didn’t fancy the idea of returning Mark’s bike on the back of a truck with a conrod sticking out through the barrels I checked Geoff Hall’s Corsa test (August ’84) and found that it’s 8000 rpm.

Switches are the old mid-‘Seventies Suzuki gear. They’re crude but effective, and the control levers are long, straight pieces which aren’t the best for those with short fingers.

The fibreglass fairing has the tallest screen around on a sports bike, and this proved very effective in protecting my upper half from both wind and rain, but with no lowers the legs are exposed to the elements.

The SFC is obviously a bike which, in most respects, is built to a standard and not a price, and this shows in the quality of the chassis componentry and the exact matching of part to part. While the near new test bike’s paint, chrome and alloy finishes were good, Laverdas do tend to go to the pack here if regular cleaning and polishing (not to mention a garage) aren’t provided. Still, anyone who shells out nearly $12,000 for a bike and isn’t prepared to give it plenty of tender loving care has probably got it coming.

If you’re not satisfied with the performance you get for your money, there are a few factory options claimed to improve the SFC’s performance in a number of areas.

The Germans get different cams to everyone else. Called P1s, they are like the cams fitted to the early Jotas, and are claimed to give improved responsiveness and smoothness through more lift. For around $600, you can have a factory three-into-one, ram tubes, airbox modifications and 135 main jets fitted (118 stock). Better low-down grunt and a smoother motor with more performance all round is the result.

A point worth noting is that most SFC and Corsa owners run some fuel additive, such as Moreys, through their bikes every few tankfuls because the motor’s 10.5:1 compression ratio dictates the use of 100 octane petrol. Our super is 98 octane, so the additive is necessary to prevent the buildup of deposits in the combustion chamber. Unleaded would strangle the SFC inside a week.

Naturally tough

Overall, the SFC is a curious mixture of the old and the new. The motor shows that no-frills technology can still deliver performance which is satisfying even when compared to the latest nut-crunchers from Japan, while as far as suspension goes the Marzocchi components front and rear are close to the best there is, and the front end especially proves that anti-dives, air-assistance and unlimited adjustability are no substitute for a well-matched spring/damping rate, albeit via fairly radical means in the Laverda’s MIR forks.

The SFC is a lot closer to the likes of the GSX-R1100, GPz900R and FJ1200 than most other Europeans apart from the K series BMWs, and as any Laverda owner will tell you it’s a hell of a lot more refined and civilised than the triples of old.

But it’s still got a mean streak that the abovementioned bikes lack. Maybe It’s the rumble and roar of the engine as It warms to the task, or perhaps the fact that it needs to be ridden harder to give Its best. I don’t know, but a Laverda owner might be able to give you an idea.

By Bill McKinnon, Two Wheels October 1986.

Ian Falloon wrote The Laverda Twins and Triples Bible, the definitive guide to this now sadly departed Italian maker. See it here.