1980 BMW R100S

For Captain Flashbulb, (aka Kel Wearne) long-distance rally runs on BMW’s R100S and RT created new impressions of the Bavarian Boxer in a realm beyond mere massed panniers and fairings.

Here are three marques which, despite all the crap legislation which brings bikes closer to one mould each year, still mark the individual character and outlook of the owner/rider.

There’s Triumph, hallmark of a magnificent past and last vestige of British Tradition; a machine with the feeling and intensity of sporting bikes which stir the blood. Then Harley-Davidsons, a heritage of locomotive power, and brutal beyond any other bike in sheer, overpowering strength and commitment to the “Other Side”.

The third is the BMW. The Classic Representative of the “Big Tour” (as epitomised by the R100RT) and one with a following less committed to display, more to riding.

A BM owner tolerates rubbishing from the uninformed, and the general covetous vibes of others as they understand more of the breed’s capabilities. He also gains entry to the club-like atmosphere; the warmth and special affiliation of BM owners born of a sensation of superiority, and sponsoring a sometimes infuriating affection which seems to come to all those who pay the $4000 plus for the Bavarian twin.

BMWs have, for some reason, a band of very one-eyed owners who believe emphatically that they ride superior machines. Perhaps the effort many make to acquire their BMWs gives them that. After all, the bikes are priced well beyond any “impulse urge” and some of the buyers must stretch themselves to own a new BM. But in this decade of constant changes, of “new innovations” (like the Japanese discovery of shaft drive), the BMW retains a class and status beyond most machines. A heritage though, which occasionally shows signs of age and yet retains the BMW aim of serving the motorcycle rider with simplicity, quality and reliability.

I don’t know for sure just how reliable BMs are (lots of stories about all bikes), but I am positive that BM owners get quality and basic, honest motorcycling. And at a time when you can’t even get a simple indicator stalk for a CB900FZ (after a year and a half out here) and all Japanese distributors just cannot cope with the spares for each range, the BMW line is all okay – availability is certain and swift.

And that is something many owners quite rightly consider an absolute essential for enjoyable, year-round riding under all conditions. BM owners can have parts flown anywhere in Australia to keep them running. Some Japanese big bike owners have to wait six months for simple items and being off the road through lack of supply is one quick way to get turned off a brand.

With the BMWs there is a continuity of design, an amortised run throughout the 100 Series lineup. Each bike has the same running gear but deviates from the Pure Tour concept into mild sports touring, all with the single-minded purpose of providing a broad base of riding appeal for those into riding distances. For of all bikes, BMWs are made to cover long distances easier, more comfortably and with less fatigue than any other bike (except, perhaps, the Guzzi tourers).

Price keeps the BM exclusive, but any rally experience (and I’ve ridden to two recently) makes the marque’s low sales figures seem absurd. At least every third bike is a BMW.

They might be scarce on the general scene and around the cities but they dominate the Big Runs. It says something for the powerful following the marque retains against the big push from the other side of the world and the continual, unavoidable cost pressure. The West Germans face this through their very low rate of inflation (around one third the Australian/USA rate).

In some ways BMWs are an investment, because no matter what happens the twins will not get cheaper. And they last a lot longer than Japanese machines which cost around two thirds the price.

Solidarity: the theory and practice

Quality is a strong point, although the R100S model did not have quite the same fine detail finish of the RT. The S model is the bottom of the range in Australia for the 100 series. The RS retains top billing as the sports tourer ideal, with the shape and cockpit fairing which has influenced the world.

The RT version, tested in conjunction with the S, is the “sleeper” of the range – plush, immaculate-looking and Pure Tour with a lot of built-in features for those who want to ride without ever having wet socks in the city.

Essentially, the S has been on the market for six and a half years, from the first arrival of the R90S. Its heritage goes back to 1923 when the basic package was introduced to the world. And in a world besieged by the annual update the basics have never been forgotten by the Germans who build the big boxer twins.

When Japan discovered the big single, BMW already had two 500 singles working together for “single-minded” top gear touring. When Japan discovered the shaft BMW had already refined theirs to absolute precision (the current BMs change more easily – with or without the clutch – than ever before), and the new additional cush drive in the tail section of the shaft has combined with the updated gearbox to limit the torque rocking motion and up ‘n down suspension rocking with the opening and closing of the throttle.

The two BMs tested for this Open Road article were ill-fated. The beautiful RT was, after the Worlds End rally, taken by Dave Sanders who rode beyond reach on his own special road in Sydney on that bike.

The S model was the only one in BMW Motorsport colours· in Australia and had been run in and tuned by Stephen Adcock. But during the Bingara Rally yours truly ran out of road at high speed with pillion and gear and broke another record (it’s been a good few months for that…hit a car for the first time, too) by crashing with a pillion, and that had never been done in 22 years’ riding!

The BMW survived the barbed wire “catch fence” with a broken crash bar, fairing and damaged mudguard. At near $150 the small bikini fairing shows why BMW owners look after their machines!

The dirt road to the rally property was fast and slick and we had been warned of a couple of deceptive sections. Keeping up with a couple of the flying BMs from Queensland (who had been into the property previously) we entered a braking area too fast and by the time I had checked out the turn it was no-go. No excuses. Off the road and into the fence. Turned out I was the third. One for every year the rally has been held!

So three BMs have done the trick on that corner. Nice to know you are following a trend!

It did mean missing the afternoon gymkhana events, but not the evening barbecue and raging. This event is by invitation, and much smaller than the Worlds End rally; some 200 bikes, about half from all points north (even Cairns) and an interesting variety of friends from BMWs to ancient Harleys, Ducati SS models, XS Elevens and other Japanese multis. Did not see many GS850 Suzukis on the two rally runs.

A constructional line

All the 100 series (RT and S inclusive) now have the top of the line RS engine but the Motorsport special still had the ’78 “halfway sports” engine with a three kW deficiency but the same torque figure as the RS.

The engines in the RS, RT and S are all rated at 51 kW at 7250 rpm (redline) with 77 Nm torque at 5500 rpm. But the BMWs have a spread of useable power not found in Japanese multis which translates to ability to overtake lines of traffic without shifting down one or even two gears, pulling past the lines, up hill accelerating, while carrying a pillion and full camping regalia. This LazyJane riding saves constant concentration and sure, there are faster bikes but there one is using the gear lever to make it all stay on the groove.

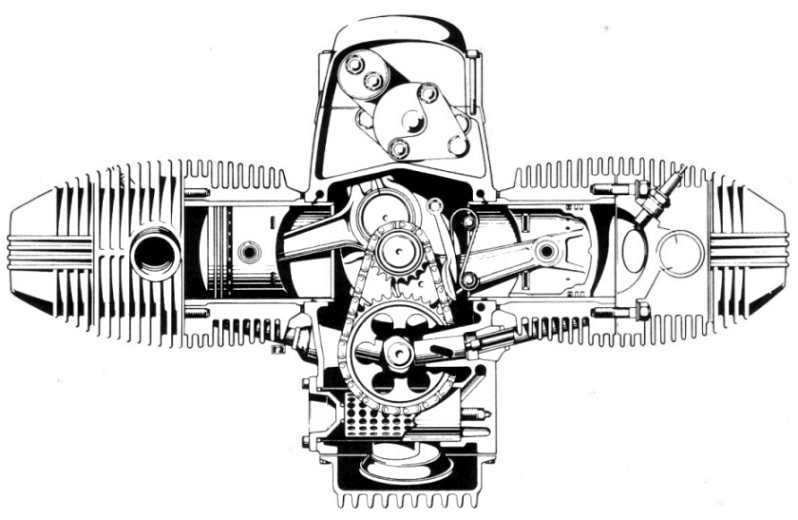

The BMW engine is light and low, keeping the centre of gravity low, with the cylinders out in a constantly exposed air stream to aid cooling. The pistons in the big twin are Mahle or Kolben Schmidt forged and have three rings. Compression ratio is 9.5:1 on a bore of 94 mm and stroke of 70.6 mm, giving an actual displacement of 980 ccs.

The one-piece forged steel crankshaft uses plain bearings at each end and also plain bearings for the big ends of the I-section drop-forged steel rods. The front of the crank drives a 280 watt alternator and this, coupled with the 28 amp hour battery, ensures you will never need the optional kick starter. There is a single row chain from the crank to the camshaft over a slipper guide and hydraulic tensioner. The chain even has a joiner link for quick service.

The four-lobe camshaft works hollow steel lifters to steel-capped aluminium pushrods which act on the simple rocker arms through screw-type adjusters. Strong, single springs return the 44 mm intake and 40 mm exhaust valves. It’s all quickly accessible to anyone with a modicum of mechanical skill, which explains why BMs are handy for beside-the-road rebuilds.

The camshaft runs at half the crank speed and so too does the ignition breaker points’ twin-lobe cam. There is a self-aligning Oldham coupler between the camshaft and points shaft, isolating the points from harmonic disturbance from the crank or camshaft.

The two sets of points fire together with the 360-degree throw crank, meaning there is one waste spark each firing. The 100 series has dynamic adjustment this year, meaning the timing and points can be set with the engine running. All of this gear – micronic-paper air filter, alternator, points – is hidden by the large alloy cover in the front and over the central portion of the engine.

The BMs have an automotive-type single plate dry clutch which is cable-operated. The sheer inertia of the high torque engine, coupled with the heavy, positive clutch means racing gearchanges are not on. The BM will change smoothly most times both up and down. I did a lot of clutchless upshifts but there is still the need to pause and let things match up. This slight time-lag is neither good nor bad, it is just there as a characteristic of the RT and S (and the RS).

The gearbox is a self-contained unit which can be removed from the bike with the engine in the frame – a good point. It has nearly a litre of heavier gear oil, a feature I like on any bike. The jack-shaft which transfers power from the clutch to the gearbox mainshaft has a built-in ramp-spring cush drive. There is a new heavy spring cush damper on the rear section of the driveshaft and this certainly improves the BM’s smoothness and gearshifts and lowers the rocking motion of the twin.

The gearbox has five speeds with a final drive ratio of 2.91:1. Tall. There is an optional 3.0:1 final drive axle ratio available (as fitted to the RS and RT models) and this would undoubtedly assist the S on the open road. The S will run out in top gear faster than the RT and pretty well more than the full fairing-fitted RS. Acceleration is better too, in rolling bursts as well as from stationary.

BMW’s frame is the same on all the 100 series; dual cradle oval section steel with inner tubing in the rear backbone main tube. The bolt-on rear sub-frame section is still there and as mentioned in the RT test last month, not a feature I agree with at all. The steel and alloy steering stem gets tapered roller bearings as does the swing arm.

The centre stand can be used in most instances but when laden the bike is touchy. The stand needs to be wider. The long sidestand, like the RT, retracts automatically when load is taken off it. Tricky until an owner gets used to it. Even then, I didn’t like to leave it alone in crowds for fear someone would sit on the bike while talking and rock it a little, take the load off the sidestand – and say no more! But if we have to live with pull-in clutches to start Kawasakis I guess we can live with selfretracting sidestands.

The BMW cast alloy wheels come with an intricate multi-spoke pattern which at first glance looks tarty. However, like the majority of the items on and in a BM, there are reasons for the design. With ten main and 20 support spokes in each pressure-cast wheel they are strong – certainly stronger than most cast wheels around. The factory knows the rough ground and loads which owners will tackle on their BMs.

But the wheels are substantially heavier than the steel rim and individual steel spokes which they replace. And I still like the old spoked wheels because these can absorb shocks where the cast wheels cannot.

From the cockpit

The running gear, like the frame and engine, is the same on the S as on the RT and RS. The BM forks are plush-to-soft. The RT had the heavier springs which Australian models get but the Motorsport S did not have them fitted at the time we had the bike because essentially it was a “display” model. Actually, that says a lot about the BMW ethic: that the company was prepared to allow us to rally-ride a “display” model. To the Japanese that would be unthinkable!

The bike’s general behaviour did reflect the lack of suspension firmness, giving me the old constant rocking motion and settling through nearly half the 203 mm of fork travel just when seated.

Current models have the stronger springs the same as the RT. The rear units are heavier ones for the local conditions but even so we ran both the RT and the S on maximum spring pre-load (adjustable by handles fitted to the units) and still found them bottoming. Perhaps owners get used to it, perhaps some don’t ride quite as hard (although after seeing the hard core BMers I doubt that), but there must be ways of making the bikes better under hard riding use and with heavy loads.

However, where the Leisurely Relaxed Tour principle applies (as distinct from the infamous Rally Sprint), the forks and rear end (with nearly 130 mm of wheel travel) function extremely well, with no jarring, a general floating feeling and certainly no shocks to the rider’s wrist.

The S has better bars than the RT, short, 50 mm rise sports bars, Magura controls and the new and better side-to-side turn indicator movement instead of the up and down. The bikini fairing protects the rider’s upper body but I would prefer the handlebar-mounted sports fairing to have provision for hand protection as well.

The riding position is more “lean-forward” than the RT and the rider doesn’t get the cold blast around the back which the RT provides as part of the “protection package”. The tank retains the slight indentations for knee grip and the offset pegs have thick rubber padding for the rider and the pillion. The 40 mm CV Bings carburettors are large and can still interfere with some riders’ shins and feet. I had no problems with them at all.

The H4 headlight is the same on the RT and the S. But the S is easy to adjust, even while riding. This is handy because the load factor affects the long-travel forks. The RT is a big problem to adjust. I ended up using a car tyre lever on the RT to force the light up a fraction at a service station one night.

Like the RT, I had occasion to do a tyre change (always doing a full comparo. I put a couple of tyres on the RT, a flat and a new Pirelli). The S went flat back in Melbourne, and again, despite the way it is meant to be easy, getting everything back in is not the simple chore it is made out to be when you are by yourself.

The long rear guard inhibits easy fitting, but unlike the RT I did not have to remove the rear guard and storage box and tail light to replace the inflated rear tyre and wheel. The S was just a little battle but I would not like to tackle it (or any large machine nowadays) at night by the side of the road.

The twin discs on the front of the S and the single disc on the rear are the same as the RS and RT ones. They’re drilled for some reason, though certainly not to aid wet weather braking, for BMs are still amongst the worst in that area along with Honda, Suzuki, Yamaha and Kawasaki. In the wet one must ride with light finger pressure on the brake lever to keep things nice and hot to ensure the brakes will work instantly when you need them. I know that’s a controversial one, but in a forthcoming article I will detail the only slotted pattern on disc brakes which has been proved to improve wet weather disc brake performance.

The S braked better than the RT – more evenly, more consistently and without the pressure required on the RT to achieve front wheel lock-up. But this is a sound principle and the BM brakes are probably an adequate compromise. Cafe blasting brakes are just not necessary in BMW Tour-Land. And considering the distance ridden on dirt roads on the test bike the BM brakes must be rated as well-balanced overall, and, despite their lack of accuracy and total precision, are still my choice (as is the whole bike) for really fast and safe dirt road exploration.

The S gets a similar console to the RT, a speedo and tacho with voltmeter and quartz clock. And naturally there is the full toolkit, a manual, pump, first aid kit, puncture repair kit and the large steel security cable and lock. Again, proof absolute that BMW displays genuine premeditation towards what the rider needs, will use, and appreciate. I’d like to see any Japanese factory hand, engineer, designer or executive do anything to a big multi, using only the standard toolkit by the side of the road in the rain, let alone major surgery. BM riders can do it all. It’s a significant design philosophy difference.

Bingara and bust!

The rally for the S was north of Sydney, some 40 km away from Bingara which is situated between Inverell and Moree, and within a short hour’s ride from Mount Kaputar (1510 metres which is near enough to 5000 feet) and some top country indeed.

Being in Sydney at the time meant the ride was short by Open Road standards, but there was still plenty of tripping around and eventually the ride down the coast to return the S to BMW in Melbourne. With typical freelancer and freeloader aplomb, it was finish some priority work, do the rounds and eventually, around midnight, pack the bike and collect the pillion passenger, leaving Diesel City at 2.40 am Friday night, which provides a very fast “out” along the Pacific Highway.

Good, solid blasting at just below 170 km/h on the expressway and punting in and around the humpy roads of Kurri Kurri then Cessnock to hit the New England Highway at Branxton, between Maitland and Singleton. Would have done the Putty Road but no-one knew if it was open or not.

The river mist at 4.30 am was brisk, cold and an ideal time to stop and get into a mixed grill and talk to some truckies moaning about “consorting” between state politicians and the exaggerated costs of more than $1200 a month to run a standard 18-wheeler rig. They must have the same feeling about being stuffed as bikers do – highways in killer condition (except parts of freeways and majority of the Vic major roads); the enormous revenue from petrol and road tax going on general items and not back into the road system at all. Sick man.

Really off are those people who sit up there and order it all – then sic the patrol/radar dogs onto us for “protection” or that hollow word “safety” (speed is a killer!) and take more than $5 million in radar fines in one year in NSW.

Can you believe that, all in the name of safety? Because none of these politicians ever drive anywhere they have no concept of what it is really like and nor do the bulk of the safety committees (do they ever get out of town?) and university superbrains who make up the statistics to read what they want and form the witches hunt.

Oh boy, is it good to have a rave with tough truckers bitchin’ as the coffee warms the numb brain and hands and the sun lifts the veil of mist to reveal the open sheets of wheat, the sheep and rolling hills near Aberdeen, out of Muswellbrook.

The early morning emptiness gave way to movement and a warning from the truckers about the 8.15 am Man – and they were right. So it was easy cruising but with the warmth of the sun, the gentle rolling rocking of the white BM, it was also nod-off time and we had to make two short stops for heavy coffee and a couple of truckers’ delights, Stay-Awakes, to make the midmorning session to Tamworth, busy with shoppers while the pillion was hanging off the back, dead to the world, despite some knee graunching and bouncing on the sharp humps around many of the tighter turns.

The S had the slightly less powerful engine to what is available for 1980 and while it was equally as responsive around the city and more than a match for the RT when ridden solo and the RT two-up, there was a lack of top end revs when in the similar loaded condition to the RT. But it would pull like anything and provided one didn’t want to make the times I was aiming at, the S was fine and cosy. Fourth gear gave a better ride all round, allowing steering changes during cornering at around the 165 mark.

The riding position was more natural than on the RT but the full protection was missing. The screen needs to be about 50 mm higher or have a small flare along the trailing edge to stop those healthy bugs spreading themselves across the rider’s visor.

From Tamworth it was north through Manilla and once away from the New England Highway the road condition dropped alarmingly, becoming narrow, changing in texture, surface condition and without the numerous warning signs. Back-to-the-Bush riding. It was tight and rough and despite trying, the best we could manage was 120 to 140 with reason.

Near Barraba, just after a one-lane bridge with fast sweeper approach, we stopped for a group of guys doing a roadside vigil collection for Apex. Someone had gone off that S bend exiting the bridge, straight through the armco into the swamp below, but nothing was there. Gave my $2 and continued into Bingara and the crowded scene at the pub, complete with TWO WHEELS’ own Geoff Hall and the Adriana from Worlds End rally debut.

Pressing-on thoughts

The S is much lighter in the steering than either the RT with its weighty Vetter-style fairing and the RS with the BMW sports fairing. The softish front forks mean a lot of nosedive over undulations and certainly under brakes the steering angle and trail diminish to trials type geometry. And despite the lighter weight the S was definitely not as comfortable when being pushed in mountain sections.

There were enough messages from the rear of the frame and front end weaving for me to desist from pressing that last 10 km/h. I have already said that the Guzzis are better-handling machines at speed on bitumen, but that in general form the 850T and 1000SP are in too mild a condition to punch it out with the BMs. But braking and handling are superior the BMs – no doubt about it. Of course Guzzi has not yet fully overcome the rocking torque effect, nor the gearchanges, in the same smooth manner BMW has done.

The rider must allow the BM a healthy gap before a corner to get into the right gear and keep things smooth all the way around. Any change in throttle, backing off or trying to shift will bring on a gentle wander and if you hit some humps or nasty bumps at the same time, the gentle action becomes fairly brisk and savage. The RT, with the greater weight on the front and the better-suited heavy duty suspension was superior in highway handling (which is not cafe blasting but we did get down to the rocker cases a few times and on the Open Road that is not common for me).

Throughout the testing of all the BMs, from the mighty little R65 to the RS, I have been surprised at the way one must move the bum regularly to remain comfortable and continue the long ride. The seats are firm although well shaped, and fairly hard across and along the edges and despite the friendly ergonomics one must shuffle around more than anticipated – certainly more than on Guzzis and big Suzukis.

A minor point though, because this doesn’t eat into the rider at all. The BMs are still fatigue-free over long runs, allowing the rider to finish the ride and party on instead of falling for the nearest chair and grabbing for the Tequila. And for all-round riding, not just sight-seeing, the BMWs can mix fun with touring; unlike the monster GL1000s, the Z1300s, the XS Elevens and so forth which, when fitted out with fairings and panniers, look like some primeval whale given wheels and about as cumbersome as a blind rhino.

The run back to Melbourne was solo, fast at night in gales down the coast then getting serious on the Vic side, sitting near 160 most of the time.

The Metzeler tyres are not, in my opinion, top tyres for pressing such roads when wet but offer long life and stable performance within the limitations of the compound and design. Under brakes the front works well but I would like Pirellis on any BM I bought. However the Metzelers certainly work on the dirt, whether graded, mixed clay and gravel, or mud.

It is a fact that at no time did I ever get consumption of 17.75 km/l (50 mpg). This is becoming a magic figure for larger bikes and one I have not seen on my notebooks for more than two years apart from the Harley. The BM’s best at all was 16.4 km/l (46.4 mpg) which was fractionally better than the best the RT provided. The worst was 11.1 km/l (31.5 mpg) which was a big difference against the worst on the RT (9.5 km/l or 26.8 mpg).

So the RT had an average of 115 km/l (32.4 mpg) while the S model, which was ridden slightly harder in my book, due to more constant use of fourth gear returned an “average” of 13.8 km/l (38.9 mpg) which is significantly better than·the RT.

I feel that with the current engine, same as the RT, the S will do even better. Thus the fairings really take the fuel consumption up, no doubt about, it. The 24-litre tank offers around 320 km as a reasonable figure between stops but the longest we did was 252 and the fill-up figure was 17 litres, leaving seven in the tank. The RT we did run completely dry near Cobar, and believe it or not, the distance on the RT was 252 km!

Conclusions

So BMW remains with its own mystique, its own character and its own special followers who’d rather fight than switch. But the marque is not attracting great numbers of new BMW followers.

The big twin offers confidence within reasonable riding boundaries, ideal wet weather riding through low impulse, low-rev riding (no wheelspin), a comforting vibration through the tank and seat which dwindles over 3500 rpm, and a low burble from the exhaust. All low profile, but both the RT and S offer something special in the combinations of low weight and substantial suspension travel, low maintenance, high resale value and good quality.

And all within the parameters of the Grand Tour/Leisure Trip/Open-Road-Laid-Back-Run, and although neither are hardcase back road machines nor Open Road sprint machines, they will maintain the magic ton-up figure all day with an extremely low fatigue factor. It’s a simple design with old world charm and I think many riders would appreciate the BM flavour.

For those ready and willing to try, the RT and the RS retail for around $6395 while the stronger-engined “S” Sport sells for around $5995. All with 12 months unlimited distance warranty. Not a bad way to start.

By Kel Wearne. Two Wheels, April 1980.