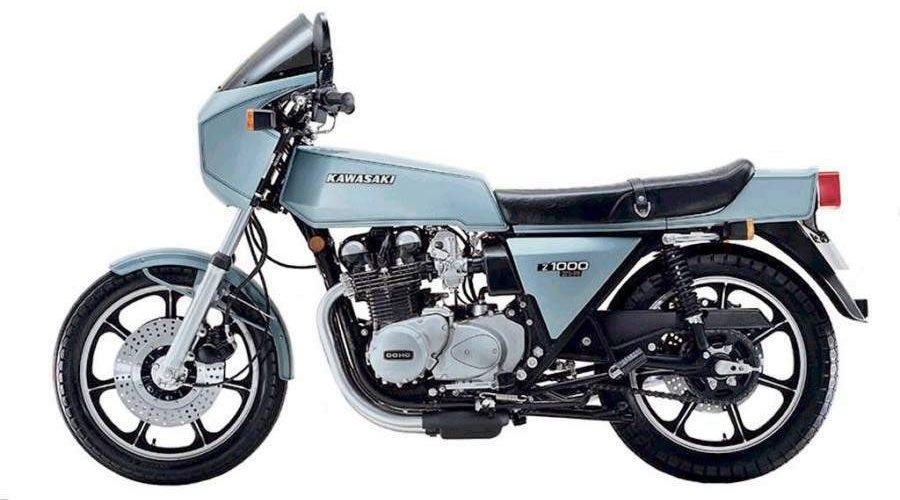

1978 Kawasaki Z1-R

Kawasaki has launched the Silver Bullet as its answer to the opposition’s total performance quest. The Z1-R makes the King Kawasaki into an instant classic and one of the best bikes we’ve ridden. Strong words, but tester Kel Wearne thinks the Z1-R is the right combination, one that sets new limits in what sheer sports motorcycling is all about.

There aren’t many bikes that hit you right between the eyes. The Kawasaki Z1-R does it two ways. It hits you right between the eyes when you see it sitting still; a bold, angular, muscular steely-etched powerhouse. And the Z1-R hits you right between the eyes (only they ‘re at the back of your head now) when you give it a fistful on the road. Any road, any time.

There is no pretension about the new King. It isn’t a commuter or general use bike. The Z1-R looks fast and tough and carries with it an arrogance that says it doesn’t have to prove anything; the facts of the past six years prove the power, stamina and durability of the Kawasaki.

The King has ruled. Not always justly perhaps; witness the many frame alterations the real go-fasties did to their bikes. But it ruled with a sceptre of strength, unmatched power, economic realism and the ability to cope with everything people threw at it.

The current challengers are the huge Yamaha shaft drive XS1100, which lacks the nimbleness to make ground in the arenas where the throne will be tested; and the Honda CBX1000 and Suzuki GS1000 which have yet to face the task of gaining loyal subjects.

The new Kawasaki started selling to a summer-eager public at least seven weeks before the first of the opposition challengers arrived, the GS1000 Suzuki, followed later by the Yamaha XS Eleven. The Honda still had not been released when we went to press.

In addition, the Z1-R Kawasaki carries its heritage. Just about everyone knows that the Kawasaki is sound value. Most figure that the new version would be much improved to match the latest designs from the other Japanese Big Three.

And on top of the established reputation, Kawasaki – conservative Kawasaki Heavy Industries – has produced an elegant, well-balanced, future bike, a blend of subtle design styling and time proven machinery. The Z1-R is a tribute to what powerhouse sports motorcycling should represent, not only in the eye of the owner but also in the eye of the everyman. In the Z1-R the King has come of age!

The new model will not replace the Z1000. The Z1-R is the flashy leader of the fleet but retains many components of the standard 1000. The claims by the company that the bike has more power are true. But the increase is not great, from a claimed 64 kW at 8000 rpm for the Z1000 to 67.2 kW at 8000 rpm for the Z1-R.

There has been no sacrifice of the incredible reliability factor to get the additional go; the engine is virtually the same as a Z1000. The power comes from better breathing and bigger carbs. Any owner of a big bore, modified Kwaka will know there’s a lot more power waiting if one wants to get into the engine, and the reserves of reliability are phenomenal.

The Z1-R gets 28 mm Mikuni VMSS carbs against the Z1000’s 26 mm Mikunis. The new design includes a tuned four-into-one exhaust system which the engineers found produced more power than the Z1000’s four-into-two system. The engine didn’t seem as smooth under 3000 revs as the Z1000, but the difference was marginal.

The powerplant is basically the transversely-mounted four-cylinder double-overhead cam unit. The bore and stroke, compression and valve timing are the same as the Z1000. Even the gear ratios are the same internal and final drive.

The gearbox, the clutch, the built-up crank, chain-driven camshafts, are all among the strongest items in any big-bore charger. It remains one of the most capable powerplants available.

The changes made to create the Z1-R as a total concept, cafe racer motorcycle were more than just outward design and engine. The frame, long the subject of discussion among the hard chargers of the big-bore rough-road set, is based on a Z1000, but with additional gussetting at key points in the frame and the use of heavier gauge steel in these places.

The heavier work can be seen under the tank around the steering head. This strengthening is done all around the frame including the swingfork which pivots on needle roller bearings.

The improved Z1000 forks are used at the front with slightly stronger rebound damping. At the rear the Z1-R gets new sports shocks with wide bodies to hold additional oil and resist loss of effectiveness due to heat build-up. Two separate springs are used on each unit and there are five preload settings to control the spring rate. Damping is much firmer to add to the sports ride and the changes in preload setting make more of an effect per couple of notches than any other shocks I have had on Japanese machines. Front wheel travel is up a little on the Z1000 to 130 mm while the rear wheel travel is the same at 90 mm.

Very obvious changes are the front and rear wheels – Kawasaki’s own cast aluminium wheels in black with polished edges, and three drilled discs. The front twin discs have calipers set behind the fork legs and the rear caliper sits above the disc, behind the right hand rear unit, with the torque rod in compression down to the swingfork. The discs are drilled not for looks and not only to work better initially in the wet. The drilling means better heat dissipation, sure, but it also means the pads can have a much greater metal content and thus can be made to perform better all round. The drilling also reduces weight slightly. In fact the Z1-R and the Z1000 scale in at 245kg each.

The front tyre is a 3.50-18 against the Z1000’s 3.25-19. The rear is still a 4.00-18. The tyres on the test bike were Japanese Dunlop K87s, semi-block rear, rib front.

All of these items fit within the visual image of the bike and help promote the concept of rapid movement even when it is stationary. The R gets low, practical handlebars and a bikini quarter fairing (which unfortunately doesn’t angle out near the front indicators and provide some air protection to the rider’s hands). The indicators, by the way, are dead ringers for the BMW square units.

The Z1-R was styled by Kawasaki’s US design studio and is dominated by the silver paint scheme and black highlights. The front fender moulds closely to the front tyre, the edged fairing looks magic, the tank maintains the angular, masculine lines of the fairing back through the seat and the excellent silver sidecovers and, finally, along to the flat squared-off fibreglass tail piece. The R is a visual knockout.

Behind the smoked screen of the fairing are a large speedo and tacho plus a fuel gauge and an ammeter, set in a BMW-like console. At night the bright green lighting of the four instruments within the fairing is neat, but the needles on the ammeter and fuel gauge are not tipped and difficult to see. All the warning lights are in the console, plus a head/tail light failure warning light. The R is fitted with a H4 quartz halogen headlight (60/55W) and this is one of the strongest patterns around for fast night work.

One of the changes brought about by the fairing is that the front disc’s master cylinder is hidden away on the left fork leg behind the fairing. A short cable runs from the brake lever to the actuating rod on the master hydraulic cylinder. This makes brake lever adjustment for hand sizes easy and doesn’t change the feel, or the pressure required, to make the brakes work effectively.

The lock-out starter system is retained; you must have the clutch lever pulled in to start the engine, as a safety precaution against having the bike lurch forward and fire up if started in gear. The indicators have a novel three-way switch which allows either a four-way emergency flash similar to car warning mechanisms, or manual indicator cancelling, or automatic indicator cancellation after about five seconds.

During the test we had to remove the rear wheel to replace a tyre. The bike had been given a hard time at Calder as well as at the Heathcote drag strip and ridden by a number of riders. The rear tyre was gone by 2000 km. When fitting a new one we found the rear wheel can be removed easily by one person; the design makes it a lot easier to change tyres than on previous models. The new cast wheel also has a much larger cush drive arrangement to help smooth out the power impulses from the chain drive.

The new tank, which holds a ridiculous 13 litres, has a fine shape with a flush fitting, locking cap. The initial feel was that the angular sides would be tiring for a rider where the tank met the seat, but during three weeks of riding, including a number of long trips, this didn’t occur. The seat is wide and firm and again seemed sure to get to a rider after a few hours but actual highway riding didn’t verify the idea. The seat isn’t hinged; a lock at the rear of the tail section allows the seat to slide up and off the bike, revealing the small storage area, the tool kit and the airbox and battery. The underside of the seat holds the emergency kick start lever, for use if the battery or electric start fails; a handy idea and one which is valued after push starting a Harley for a couple of days and also a Laverda 1000 triple once.

An effect of the Z1-R’s styling is that the bike looks much smaller than the Z1000. This is really imagination, but despite knowing it is an illusion, the R still feels smaller. The weight is the same, the frame geometry is the same and yet the bulk of the Z1000 seems to be missing.

One thing which helps a little (but again is only a partial change) is the fact the seat height is 810 mm while the Z1000’s seat height is 827 mm.

However, styling magic aside, the Z1-R has a new feel and a completely changed character out on the road. It does almost everything the standard Z1000 does but it’s essentially a go-fast tripper. It isn’t your everyday hack workhorse, commuter, tourer or around the block for a flagon machine. The R can do the mundane, but that’s the least of its image. It’s a mixture of muscle, pose, style and speed, one of the most stunning machines ever to hit the streets.

As an improvement the ground clearance of the R is superb. The engine may be high and the big four-cylinder must of necessity have a high centre of gravity, but like the Laverda 1000 triple which is also stuck with the same problems, the Z1-R has been planned to cope with high-speed running without things dragging and without the past characteristic understeer at speed or fall-in oversteer in slower turns.

The Z1-R remains heavy at the front and the steering is firm but it’s also accurate beyond any other Kawa. The bike runs where it is pointed and holds a set line on rough bitumen sections, very similar to the heavy but accurate and expensive Laverda characteristics.

The engine is further forward in the frame and there is a lot more weight on the front. The new wheel and tyre copes with this and provides extremely accurate medium-to-fast steering and feel. There is an unavoidable lack of precision and some weight at slow city speeds, though.

Before going into the ride and handling in detail, I should discuss the speed of the Kwaka. After all, for the past five years it has ruled as the quickest stock bike anyone can buy. The Z1000 has a claimed 400 metre time of 11.9 seconds. Well, like many claims this is difficult to do under test conditions with various track surfaces, different riders and perhaps just out of tune engines and bikes not super set up for the occasion. Also the standard tyres don’t provide the best traction one can put on to a thing like the big Kawasaki.

Realistic times for the Z1000 were about 12.6 seconds and this is something an owner could expect to do. The Z1-R was ridden by a number of journalists, some very experienced riders and also top racers such as Bill Crawford and Mick Hone and also the Australian National Drag champion Peter Allen.

At Calder on the demo day with the bikes brand spanking new with less than 300 km up, we did hand clock checks of about 12.5 seconds and this was fast. Subsequently the best times were around the 12.1 to 12.3 second mark. It may be we have become used to what figures represent, because this figure, with a Japanese rear tyre on a well ridden bike not tuned for the occasion, shows it is very, very fast. The fact is the Z1-R did a 12.14 with a terminal speed of 178 km/h – the fastest stock machine we’ve ridden in Australia. So far.

The fact the bike does this time and can run at well over 160 km/h all day without any signs of distress demonstrates the bulletproof design of the engine, clutch and gearbox. A further example is Peter Allen’s drag bike which has a stock clutch in the engine and has had same without any troubles for more than a year!

The three disc brakes match the performance. The front two aren’t as touchy as say, the Italian Brembo set-ups. This is good because it’s very hard to lock the front wheel, meaning you can concentrate on riding and braking without worrying about the last fine touch to the lever. The rear brake is chattery over rough ground and still inclined to lock up in panic situations but it’s nothing more than a little annoying. When heeled over on fast turns on smoother surfaces the R front brakes can be used effectively but on rougher sections the front tends to twist and stand the bike up towards the outside of the turn.

The tautness and responsiveness of the Z1-R proves that beefing up of the frame works. The accuracy and stability of the steering is a delight, the brakes totally safe. The sheer bursting speed whenever one wants it is exhilarating.

The small fairing works well. After years of ton-plus running and knowing the way the helmet and head move around in the air rush and the subsequent strain, it is relaxing to have a Japanese production bike which protects the head and body from the pressure. Just a movement outside the fairing protection to check and instantly the head and helmet buck and rock as the buffetting of the air reminds the rider of how much strain there is on unfaired bikes. The fairing provides the right chest and head buffer and makes the R even easier to ride at major speeds for long spells. It makes concentrating and riding fast less tiring than before.

The forks and indeed the whole front end is fine. The criteria is that during the entire three weeks not one jar went through the bars to the wrists and never did the front pull a wobbly. I rate the front as good as anything around for sport and fast road riding.

The rear end, with the new units, is better than before, but there’s no way a company can make a rocketship which handles acceptably at high speeds do the same at slow city speeds. It can’t really be done because the firm, instantresponse needed at speed cannot offer a soft resilience at speeds under 80 km/h and especially around town. Humps, bumps and changes in road level, such as crossing other roads, send a jolt through the rear end. Even on the softest setting the Z1-R feels the road right through the seat at slow to moderate speeds. Not beyond reason, just similar to the Ducati SS and the Laverda triple.

At speed the rear units must be notched up to the hardest or second hardest preload setting. The bike performs but occasionally a nasty hit, especially on the secondary highways, sends the back end bouncing. But the same happens on all bikes on our rugged roads. These sudden unseen hits are never pleasant. While the new units are better than before I must admit they are still one of only four criticisms I can make of this bike.

I think the rest of the bike is so good a set of European units, either oil or gas, would be a must. Improved control of the rear end would match the fine front. At the same time I would have liked Kawasaki to angle the rear units forward a couple of centimetres to create a much more progressive movement to the back end and also to add another 30 mm or so of rear wheel travel. This would mean the standard units would have worked fine. I note that neither the Yamaha nor the Honda nor the Suzuki have emulated the road racer long travel rear suspension. It seems a waste not to follow the idea at least partway and make a compromise so that the rear end moves easier and has a bit more travel for the road user. But I imagine it will come.

After some hard weekend use two-up and with a lot of mountain racing the units did fade and I suspect that while they are better than the Z1000’s, most keen riders will feel the extra $60 is well spent on accessory units.

Also, the standard tyres, while fine in the dry, have a rapid wear rate and don’t like the wet at all. The Japanese could help their balance of payments by fitting good rubber standard from Europe! However this is minor as riders can change tyres after running in.

The remaining two criticisms are still minor. The super quartz halogen headlight is virtually impossible to adjust while riding. This came up pillioning one night in central Victoria. The brackets for the headlight are in behind the fairing and to do a proper job means removing the fairing — fine when setting it up for yourself, but with a pillion and changes in load, it is a real chore, not a one-minute operation like most bikes.

I tried the usual push the light trick whilst riding and couldn’t move the light at all. It has a lateral adjustment screw which is fine, but it needs one for vertical adjustment, too.

And the last criticism: The immaculately shaped and squared tank is too small. It means the Z1-R will be in real trouble in production races such as the Castrol Six Hour and it also means too many stops on the highway at high speed. We had a low of 12.3 km/l (8.13 l/100 km) to a best of 17.8 km/l (5.6l 1/100 km), but usually 130 km sees a rider desperate for fuel. It’s a shame, as the tank could have been sculpted out from the steering stem to the edge of the twin cam head, then angled back like a BMW tank for the knees to fit and still be just as effective in looks, maybe more so. Kawasaki would be wise to release optional long-range tanks and make these available just in Australia and Europe.

In overall handling there is no real comparison between the Z1-R and the Z1000. With the stability at speed the Z1-R inspires riding fast. The only time it shows signs of “woofing” is on very fast, rough turns where the rear may bottom out and send the bike into lurches. But the front still remains right on, no waggles or tank slappers at all.

And one other time which riders will get to know; when on a fast turn the power is turned off, such as leaving a freeway and coming up on a car at half your speed for example. This buttoning off causes the bike to stand up and move around uncomfortably. But as Bill Crawford said: “All big bikes do that when you shut off the power on a corner.” Right. You know it will happen and ride accordingly, confident that the Z1-R is one of the best of the big movers under all but the worst conditions.

In terms of handling the Z1-R has met the Europeans head on. The weight and mass of the bike still mean it’s an effort to switch the bike from one side to the other for S turns, but as a fairly short rider I found this far easier than on many other machines.

Ground clearance is excellent. On standard tyres we did wear away at the right side black metal protective plate over the collector for the four-into-one pipe, but this is set at the correct angle so that it touches and glides over the ground. And to wear into it a rider is going very hard. Harder than about 80 percent of owners would ever do. On the left there is nothing but the folding footpeg rubber unless you lay the bike on its side!

The feeling about the rear units and tyres was verified near the end of the test when I returned to K and W motorcycles of Heidelberg, Vic., who had sold quite a number of the Z1-Rs. Three had been fitted immediately with new accessory rear units and Michelin tyres. I took one with PZ2 tyres and Koni rear units for a quick run around the back street while in for a first service. The bike was brilliant, absolutely brilliant.

In normal guise, that is without the better rubber or rear units, the Z1-R still offers a blunt expression of instant speed, a styling exercise in magic, a balanced handling package way beyond most riders’ ability. It will carry two heavy males at speeds in excess of 190 km/h (we know, but don’t ask us) and it will cope with virtually everything any sane rider would come across.

The Z1-R can satisfy the racer in all of us and again, considering very few riders really expose themselves to the dangers of rash, down-and-out riding, the Kawasaki is ideally styled to make it the love of an owner’s life. At $3095 at testing time, the Z1-R carries pizzaz enough to impress anyone, performance enough to salve any rider’s demon craze, and enough sophisticated design and style to be an instant classic.

By Kel Wearne. Two Wheels, June, 1978.