1976-1984/1986-1992 BMW R100RS

The new flagship of the small BMW fleet is really some motorcycle, as it ought to be for a cool $4500 on the road. It is new in several regards, but the basic design is old, retaining the flat-twin and shaft-drive configuration first adopted by the Bavarian factory in 1923 and merely modified as the years slipped by.

The factory’s policy is obviously one of detail improvement, and has been for years, even at the risk of apparent gross conservatism. But the R100RS is at once conservative Bee-Emm in the old school tradition and yet upstages everything else in sight (including the other models in the five-bike range) by adopting a very 21st-century fairing as standard equipment and blending it to the rest of the model in a fine styling exercise.

And just to add the icing to the silver and blue Bavarian cake, the factory upped the capacity to just under 1000cm3 by boring the pots to a whopping 94mm. As well there are a whole list of detail modifications which are not so much apparent as real, and which play their part in making this the most outstanding BMW yet.

For example, the frame remains basically the same as it was on the R90S, which the 1000cm3 models supersede, but it has been strengthened under the stress points at the steering head, and is a mite heavier owing to a heavier gauge tubing in the cradle section of the frame under the engine. This helps maintain the rigidity needed for flex-free absorption of road irregularities and engine vibrations, if at the expense of some additional weight.

BMW has adopted a few more frame tubes for a more rigid assembly, retaining the box-section frame for the same reason, but it has also continued with the bolt-on rear sub-frame assembly which forms the seat base, holds the mudguard in place and forms mounting points for the top of the rear shock and the mufflers. It’s firmly mounted, but still out of place on a machine like this.

Perhaps we shouldn’t carp on such a small point, but the BMW is probably the only motorcycle currently made which has such a bolt-on rear assembly. It bolts on at two points either side of the main frame; just above the swinging-arm pivot and under the nose of the seat.

The fairing is in seven pieces, and is attached to the machine at six points. It sweeps up and over the handlebars, with the top half containing two instruments – the voltmeter and clock – and the ignition switch. A small, sports windscreen blade with beaded edge is fitted to the top and two complementary matt black mirrors sprout from the upper sides of the top half.

Just above the horizontal cylinder heads the fairing has a slightly angled vane moulded into it to provide a downthrust to the front wheel at high speed, to help overcome the lighter steering which was said to be a slight problem with the R90S.

The fairing tucks in behind the leading edge to allow an uninterrupted flow of air over the cylinder heads, with a neat little opening to allow the newly designed plug covers to be easily removed. And it’s not just any old gimmicky fairing, because the shape and positioning was arrived at after exhaustive wind tunnel tests at Pininfarina’s research establishment.

To prove this point still further, BMW has mounted the headlamp in the nose of the fairing and placed a glass lens in front of it, and blended the front blinkers into the general shape of the sides, just ahead of the handlebars. The parking light is contained within a thin strip directly above the headlamp cover.

A fluted cover fits between the two sides of the fairing to allow plenty of air circulation to the front of the engine cases, and the general lines of the panels extend to the newly shaped tank and the neat, but not entirely practical seat. A small storage bin is in the tail of the seat, accessible when the seat is unclipped and swung up. It also allows the battery to be visible and the tools to be removed if necessary.

We say the battery is visible when the seat is raised, but it cannot be removed for topping up; in fact, the distributor who provided the test machine claimed the rear sub-frame had to be unbolted and moved to the rear if the battery was to be removed for replacement. What’s more he proved this to be so, at least to our satisfaction. So perhaps there can be a use for the detachable rear-end after all!

The R100RS (for Rennsport, the proud racer name bestowed for the first time on a road machine) has the same newly designed rocker covers which are now a feature of the entire range, but they look somewhat different, though very fetching, in their matt-black finish. They are thicker than the earlier models and made of a more durable aluminium alloy – yet another hidden feature.

The engine remains pretty much as before, except for the bigger bore and lightweight pistons, but the crankcase breathing has been improved and a new system of O-ring seals at the base of the cylinder barrels has been adopted to reduce the engine’s oil consumption.

The rocker arms have been re-located in the head, and a newer valve actuating system allows alloy tappets which are lighter and quieter. The barrel cooling fins are shorter and thicker, providing a similar area for cooling, but resulting in less engine noise and a reduction in resonant “ringing” through the fins. Gone are the Dell’Orto carbs fitted to the R90S; in their place are 40mm Bings, the constant-velocity units.

Mindful of the problems in the first 900cm3 models, the 1000 retains the latest clutch assembly, but has the flywheel attached to the end of the crankshaft by stronger bolts. There should be no problems because the engine develops the same power as the 900, although the torque is stronger through the range.

In fact, the extra punch from the engine is the most obvious improvement in the new model, because it will dig in and pull like a train from not very much above a fast idle, right through to its stated maximum of 7200 rpm. Gearing is slightly higher, with the result that the 4000 rpm running-in engine speed sees more than 120 km/h on the speedo, certainly a respectable enough speed to be travelling on some road surfaces.

The view from the “cockpit” — BMW calls it that, and we’d agree — is very good, thanks in part to a very high saddle; a bit too high if you have short legs, but commanding a bird’s eye view of a lot of country.

The seat is well padded and a really great shape, but it will only accept one and a half people! It has apparently been designed to fit in well with the overall concept of the design, but the high kick-up which is a feature of the tail of the seat loses valuable space. You could fit your bird on the back for a blast round the block, but not for a weekend away. There is no way the seat could comfortably seat two average-sized people, and that’s that.

To fit the handlebars within the confines of the fairing, BMW has cropped the width, with the result that your arms are closer together, allowing a little more leverage, but making the bike just a little awkward at slow speeds in traffic. It feels as though it ought to fall over but it never does: It’s an odd feeling, which certainly won’t worry everyone.

The engine fires and runs reliably, but the idle on the three test bikes we rode (more of that anon) was similarly rough, although it varied from one to the other. It could be from the added oomph of the more torquey motor, but as it varied it was more likely to be caused by small maladjustments to the carburettors.

The transverse mounting of the Bee-Emm engine can produce an uneven rocking motion if the engine is not running smoothly, but it is not to be confused with the torque reaction to which they are said to be prey. It is enough to say the phenomenon disappears the moment the machine is under way, and does not re-appear.

The old Beemer Gearbox Blues are apparently a thing of the past, because the R100RS slips between the gears like a warm knife into soft butter, up or down. There is some forethought required in the change from first to second, but you can’t beat the box in any of the others. It makes a welcome change, and allows the hard-ridden 1000 to more than hold its own in point-to-point averages.

The new model is not a sports mount. It is quite obviously intended to cover the ground easily and without fuss at nearly its maximum speed, with the handling others envy and cannot approach.

It handles impeccably, and is one of those very rare machines which improves the faster it is ridden – within the unstated reasonable limits, of course. It is the only machine in the range to keep the friction hydraulic steering damper, and we would say it seems unnecessary, probably adopted only in deference to the stubby handlebars.

The first R100 we rode wallowed a little through corners which was a disappointment. We blamed it initially on the short bars, or perhaps the firmer suspension. But the suspicion grew that the front tyre was under-inflated. We could do nothing about the tyre at the time, but seized the opportunity of riding another example in Melbourne a week or so later, having the facilities to very carefully check the tyre pressures before the mini-test. There was no comparison, for the latter machine displayed no signs of heavy steering and could be hurled round corners with an abandon bordering on the absurd. There should be more of it!

Acceleration is not neck-snapping, but is at least very useful, the machine more than making up for this deficit with its great cornering capabilities and its tremendous stability under brakes.

The brakes are superb, relying on twin, drilled discs on the front and a single leader drum on the rear. Discs are fashionable wear for the rear, as we know too well, but the rear anchor on the test bike was as good as any you’d find on a motorcycle anywhere.

The R100RS is happy being ridden at high speeds over almost any sort of terrain, and can be flung from one extreme angle of lean to the other with no protest whatever, but the suspension is on the firm side for riding at slower speeds. Unless a bump is fairly substantial, the forks in particular don’t work nearly as well as they should. In fact, the ride can be very choppy over some surfaces.

Another machine was available for a day in Sydney, and we went out for yet another ride (we didn’t really need much excuse) and the same firm suspension was noted for the third time. It could well be due to fork springs set up to allow for the downthrust on the fairing at high speeds, because the ride was too harsh at normal traffic speeds.

But we had reason to be happy about the firm springs when the machine was blasted, however silently, over our fast horror stretch of tarred motocross road outside an outer Sydney suburb. The offending corner is a downhill left-hander with wave-like ripples running transversely across its apex, approached from a fast, smooth right-hander.

Our testers have been up on the pegs fighting monumental tank-slappers on a lot of well-fancied machinery, but the BMW crossed this very dangerous stretch of road at high velocity with nothing more than a grunt and a quick nod of its head! What can you say in praise of a suspension system which has such an in-built fail-safe device, except to rate it as A1 Plus? It could be less firm, but you can’t have everything.

The switchgear is confusing initially, if only because it flies in the face of the more-or-less universal Japanese positioning, but it is still well thought out and easy to reach. The blinker is an odd switch and is mounted on the right handlebar. It uses an up/down movement instead of the more usual sideways movement and is almost two separate switches in one. Works well, but a horizontal switch would be preferable.

The twin console instruments atop the forks have the usual bank of warning lights between them and are quite easy to read, even in daylight. The tacho action is smooth and reliable, while the speedo has an odometer as part of its information.

Lights are well up to the mark, but the blinkers cannot be seen, and one of the test machines had its warning light blown which caused some uneasiness until it was realised the blinkers were OK.

There is no doubt the new fairing is a great highlight of the R100RS, but it has two serious drawbacks. Firstly, the low screen tends to direct the windstream directly over the top and up and under a full-face helmet. We tried a jet style lid with goggles and the problem was not as marked, but sand on the surface of the road stung like hell at reasonable speeds, so the fault remains.

Secondly, a furnace-like, continuous blast of hot air bathes your steaming shinbones at mid-range speeds on hot days, courtesy of the shaped air cowl which ducts the cooling air over the cylinder heads.

The factory claims there is no problem with heat being directed towards the rider, but in Australia there most certainly is. It was very noticeable on the first machine, which was ridden in near-century heat, not apparent with the second which was ridden on a blustery, overcast afternoon. It may well be a nuisance only on the occasional very hot day in sunny climes, but the problem is there and the heat is intense.

There is another, more subtle problem with a fully enclosing fairing like the BMW’s and that is the tendency for engine noises to be amplified. It would appear that some of the detail modifications to the BMW engine were carried out in the interests of quieter running, particularly with the fairing, but there are some odd sounds to be heard which would normally be carried away by the airstream.

That’s hardly a problem, and could be lived with, but the other shortcomings of that beautiful piece of streamlining may take a while to become used to.

Fuel consumption overall was a very acceptable 14.9 km/l (42 mpg) – very good for a 1000cm3 engine – even though it is a relatively uncomplicated overhead valve twin, and a slow revving engine at that.

We haven’t been hard on the bike, because the faults it has are not particularly bad faults and can easily be lived with. The old German design has stood the test of time and is still out on its own.

Nothing much will live with it on a long-distance run, if it is ridden as briskly as it demands, and it has to be one of the all-time simplest engines to work on.

There is no doubting its strength or its purpose, or the market segment at which it is squarely aimed: It is the archetypal enthusiast’s motorcycle, the type of machine which is waiting patiently at the end of that long row of rather “ordinary” bikes we all ride before we decide to become serious about the whole thing and cast about for that almost mythical object which is “the best that money can buy”.

It’ll cost you big money, and that will make the bike fairly exclusive, but it’s a safe bet you won’t ever need to buy another motor cycle. That would be too much of an anti-climax, no matter which way you want to view it.

Two Wheels. July, 1977

Kel Wearne: A Road On Its Own

The BMW, a legend among the motorcycle manufacturers; a survivor through the fierce economic pressures of the ’60s and a stylist without equal in the performance-oriented ’70s. In its own way BMW has out-imaged Triumph and has an army of followers who’d rather walk than switch, which rivals the heavy Harley scenario.

Yet until recently the BMW was a background bike in Australia, blending into the scene as it passed through. Not Main Street Profiling. Rather a subtle mix of monied one-upmanship, a round the world touring image and a presentable, even respectable, Down Town package. It is solid executive material as far as Outsiders (read The Public) are concerned, yet since 1970 BMWs have not only been as modern as the rest, but have led the way in aspects of design and presentation.

BMW has an implied edge; the name carries the aura of top quality and top of the scene. The BMs represent Status. Elegance. Superiority. It has been building and developing the horizontally-opposed twin since the early ’20s. It had telescopic forks in 1936. Of course the looks suffered when in 1955 with the R69S series, it used the Earles forks. This carried the BM banner until 1970 when the new range was released, including the R60/5 (600 cm3) and the R75/5 (750 cm3) with modern styling, telescopic forks and some colour after the years of black.

In 1974 the 900 R90S arrived here. This was the fastest, sportiest BM to date, with twin disc brakes and luxury long travel suspension. It rocketed BMW sales and was The Success model for the company.

The image of BMs changed right then. The grand touring bit was still correct but the S model went more quickly over a longer distance than all but the best of the superbikes. It was a superb sports tourer.

Finally the ultimate model arrived: the 1000 series led by the stunning, sleek, R100RS in 1976. The appearance was radical then and remains so today, with full integrated instruments and fairing and superb finish.

Changes since then have been comparatively small, but not insignificant, including a change from spokes to cast wheels, the addition of a disc at the rear to match the front two, a longer seat instead of the sporty banana type which required close riding two-up. The latest R100RS uses a new gearchange linkage to try and quieten down the “clunk” of gearchanges, new handlebar switches also, plus the fairly wild gold/white; royal blue/silver and blue/white paint schemes.

BM owners demand the best. At $6200 for the latest R100RS, or around $5670 for the previous silver unit (still available), they expect it. There is no doubt the BMWs are excellent bikes. Whether they deserve to be mythicised is another thing.

Like the Italian Moto Guzzis, the BMWs must be ridden a long time to fully understand them, realise their potential and to explore the outer boundaries of performance.

Not straight line performance, because the megabikes from Japan will outrun both breeds of European touring twins, but BMW performance — as in living with the bike, riding it under all conditions and building your kharma with it to be aware of the experience of the bike. You can ride most bikes but you have to experience the BM or the Guzzi. It makes them harder to test, to compare and to judge, because the qualities of the machines are likely to add to your overall riding style, enjoyment and living over a long period of time, more than the average machine. One might even have to define a BM owner as one who exists to travel; not to just have a bike.

However, one can’t live with a test bike for six months or a year and the rules of the game are such that one must wear what one finds, in the three or four weeks on a bike. A return trip to Sydney was on and we opted for the original silver R100RS, with spoke wheels and drum rear brake. The very latest model was just released and not available for test. Lindsay Urqhart, manager of the motorcycle division of BMW Australia, explained that the changes to the new engine were minor anyway and that the feel of the new bike was the same — same fairing, same weight, same power, lighting, tyres and suspension. Fair enough.

The first day around Melbourne was okay for starters. The lurching flywheel torque effect caught me off guard after a time on multis and the bike has a lot of secondary vibration through the tank, frame, fairing and bars. Actually, vibration is not the right word; I’d rather call it impulses. They’re felt by the rider but are not tiring or aggravating during a long ride. Quite the opposite almost; there is a warm, pulsating message, a heartbeat sense in them. During the period on the Open Road there was no discomfort from the bike. A few shifts in bum position on the sports seat and occasionally spreading the knees outside the edge of the fairing, that’s all.

The second day dawned as a grey, wet one. The gardens were swimming pools and the autumn had gone. There were priority flood warnings for half the state and sheets of rain pounded in from the south-west, with temperature less than 10 degrees. We had arrived home from a long party just before, taking the F100 in a sliding swathe ‘cross town. The BM was safely garaged during the raging night. But the weather was still on in the morning and I wanted to test the effectiveness of the full fairing, as I had only ridden the R90S previously. With the camera gear added to the top bag of the two-layer Corona tank bag, a last check was to make sure the Hallmark nylon pack was secure from any pressure entry of water.

The rain was the Real Thing and I didn’t clear Melbourne without running through deep water across the roads as drains blocked or couldn’t cope. Out through Whittlesea it was almost like riding an enduro at Orange, with water stretched across the road almost all the way. Traffic was light. A chance for assessment — the engine lumpy between 2000 and 3000 rpm (100 km/h) smoothing out between 4000 and 5000 rpm (120-135 km/h).

By Seymour it was time to stop to fix the big mistake. Despite wearing the full overall rain suit over the usual rain jacket and trousers over leathers I had left the gloves outside the elastic sleeves of the rain gear. In the BM fairing things were hectic and turbulent with the low pressure sucking great sheets of rain and water into the cockpit region. The gloves had quickly filled with water and become swollen and cold. I changed to wool ones and large gauntlet-type with duct tape around the ends to stop water running inside.

The fairing is not quite wide enough for leg/knee comfort. It also creates a lot of internal turbulence, much more than the similar-shaped fairing on the new Guzzi SP1000.

The riding position fitted me well, although taller riders will find it difficult to keep their legs inside the fairing for long rides. The bars are ideal. Excellent switches are easy to operate with thick gauntlets on, and the instrument console is second to none.

BM has the longest suspension travel on any road bike with the front forks offering a 182 mm stroke while the rear Boge damper units allow the rear wheel 109 mm travel. A lever adjustment allows easy spring pre-load setting over three positions. I stuck with the firmest.

The forks had a revised valve structure on this model but the sheer travel means there is a rocking motion while covering the highway fast. Mind you, there is little preload setting and about a third of the travel is lost when a rider sits on the RS. It lets the bike keep track of the ground over Australian undulations like very few other bikes.

Comfortable is the word. Loafy, softish, yet without that wallowing feeling you get with the Yamaha XS650, Honda GL1000 and many others. There is no doubt one can ride a Japanese machine fast and cover a lot of ground. It’s been done. But you know you have ridden far. You are not going to feel as easy, as relaxed, or see as much on the way, as you will on a BM. While knowing it had to cater to a performance image, BMW opted for supple, long-travel suspension, on the soft side of sporty. It’s right because the plush ride is going to get you further and longer than cafe hard.

The feel of the bike in the heavy, continuous rain was still plush, rippling the Hume into a carpet ride. There were no candy cars, no domes, no nuthin’ in that three hour run to the border. Trucks, with their massive wakes of spray, gravel, mud and diesel fumes continued to add visibility problems, but I was committed to the Radar Road to Sydney.

Metzeler tyres were fitted, not my favourite in the wet but there, as with many things, the factors and the use make absolute judgemental decisions irrelevant. Like the Avons suited the big Laverda on test, so the Metzelers behaved perfectly on the BMW for the duration. Punting hard into some rougher NSW corners I waited for the slip and slide, but it rarely came. Like the Guzzi SP1000, the RS has enormous flywheel effect and. transmits all the power to the ground. It is very difficult to induce wheelspin even on the slick parts of the Hume.

Directional control and stability were excellent and steering was, for a first timer (so to speak), acceptable. The BM and the Guzzi both require careful throttle control if charging in corners. Control is good until the throttle is rolled off while still making the apex of the corner — then the rear jacks up, the bike understeers across the line and the weight transfer can get the back out of line in the slippery parts.

You must get all the gear changing and braking done before the turn, then keep a constant, steady, or gradually opening throttle to maintain the line and attitude, a technique which comes natural to regular BM or Guzzi stalwarts.

The power of the BM certainly exceeds that of the SP1000 Guzzi and a number of BM regulars, including Lindsay Urqhart and Don Wilson (in charge of the Tom Byrne’s workshop in Sydney), said to ignore the BM redline and stay on it all day if desired. That seemed a little generous but the bike is said to be happy around the 7100 rpm mark. Fourth gear is around 172 km/h at those revs! I didn’t pull it in top.

But I’m travelling. Punching through those trailing clouds overtaking Macks, Volvos, Whites, Inters and such, hoping that the sheer lack of time (it takes around 1.1 seconds to overtake a semi travelling at NHS – Normal Hume Speed – of around 110 km/h while you are on 160 km/h) would ensure there wasn’t the grille of another Mack, Volvo, White, Inter or such about to emerge from the white spray and destroy the five and a half grand’s worth of Bee Em. Not to mention ruin a good story. Apart from that, the ride up was relatively uneventful.

Oh, the rain stopped for a short time, then picked up again as the traffic became thicker near Sydney. There was one stop at Yass where the rain was quite serious, sweeping under the service station covers. Parked were eight bikes with light camping and travelling gear; Triumphs and Kwakas and one big, semi-chopped Kawa parked in the rain by itself. And one miserable sod whom I had passed pulled in behind me. Riding a friend’s RD200 from Melbourne to Maitland he was being over-run by the Muthas Out There On Their Highway. A stone had shattered his visor and his Army Great Coat had turned into an Army Great Weight. Cold, unhappy with a bike that was missing, no headlight, map or wet weather gear. He had a long, long trip.

The rain meant no radar. But the Chargers and Falcons were out in force. Pushing the BM hard to clear a line of traffic, instinct brought the RS in behind the final car – instinct and the fact all the fast cars which had been going for it after me had dropped back into the left hand lane on the divided highway. The Ford heading into town had turned around and sat behind me for 120 long km in the mist and spray and chill. Boredom of the hassled kind.

Stops to Sydney were for petrol at Wangaratta, Albury (needed coffee), Yass and then hunting a station up at Liverpool (on the weekend and everything was closed). Plus one stop along the road for pies.

The highest consumption was 12.9 km/l and the best, 19.4 km/l. This is more thirsty than the SP Guzzi which ran the same roads three weeks later. Average for the BM was 16 km/l while the Guzzi averaged 21 km/l and the CBX Honda, running on the same trip, averaged 14.2 km/l. Both European bikes have healthy 25/24 litre tanks giving a range of around 375 km for the RS and 480 for the Guzzi. The fast CBX with 20 litres, travelling at the same conservative speed (120-150 km/h on the Guzzi; 130-160 km/h on the BM) would have a range of around 260 km.

The BM was missing badly by the time I made Sydney. A trip to see Don Wilson resulted in a new plastic suppressor plug cap. These can break down occasionally. A minor fix job.

In the week and a half of good Sydney weather the BM showed itself to be a heavysteering city machine, and the fairing captured engine heat and let it rise in drumming waves. The trick is to remove the bottom half of the fairing for such weather. I’ll drink to that.

Power of the BM is nowhere near that of the CBX, but it is more than the SP1000 Guzzi. Both the German and the Italian bikes weigh in light at 224 kg (BM) and 211 (SP Guzzi) while the massive Honda weighs in around 252 kg. The advantage of the lower weight and the low centre of gravity in the BM is predictability. The bike can live comfortably with its frame and suspension and there is always the feeling that the BM is working towards giving the rider the smoothest ride without the enormous power surge the megabikes possess.

The engine of the RS is the 980 cm3 pushrod operated overhead valve with the two cylinders having 70.6 mm stroke and 94 mm bore, combined with a 9.5:1 compression ratio, bigger 40 mm Bing carbies (constant vacuum) and bigger valves (44 mm inlet). It’s easy to work on despite the full fairing.

The plain bearing crank turns in much beefed-up crankcases while a chain drives the cam, which is set below the crankshaft. A single plate dry clutch is set behind the large flywheel. The five-speed gearbox is almost bulletproof and the output shaft plugs into a universal joint at the swingarm pivot point on the right side. The driveshaft inside the swingarm ends in a pinion which drives the rear wheel’s ring gear. There is little of the drive shaft snatch and lunge which builds up in the XS Eleven Yamaha and the GL1000 Honda, after a time. Both the Guzzi and the BM stay firm without any snatch.

The one area in which there must be some doubt in the BMW (although most owners will argue strongly against any form of weakness), is the bolt-on rear subframe section. This connects to the basic single backbone, double loop downtubes and lower cradle frame. It has been gussetted around the front, tubes and around the swingarm pivot region. The BM handles most hard riding well but sets up some weaves and lurches at speed when heeled over on undulating sections.

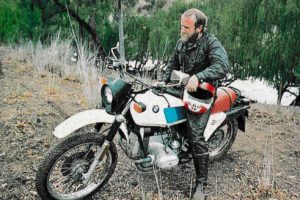

But the BM must rate as very good overall, excellent in the wet and perhaps the best road bike for the dirt. Yes, that is right — the BMs have it all over the rest if you want to tackle the many graded roads in our land. There seems to be perverse pleasure in BM owners taking the dirt road course to the rallies expecting their mates or others who have not yet joined the exclusive club of BM ownership to tag along on their Japanese machines.

The BM is the most stable, predictable and safe fast road bike I have ridden in the dirt, both sand and gravel, far better than the Guzzi SP and much easier on tight, curvecountry dirt roads than the CBX, GL1000 and XS Eleven.

The lights are fine (quartz halogen), rating near the best around. The bike feels light and manoeuvrable and has excellent ground clearance, a rugged clutch and predictable but certainly not super brakes. The twin discs and drum on the model ridden and also the twin disc front and single disc at rear (subsequent two models) are nowhere near the class of the integrated braking system of the big Guzzi. Acceptable, but not razor sharp, and very firm pressure is needed to lock up the front wheel. However the brakes suit the general functions of the RS. The one big plus is that the bike can, if really necessary, have the brakes used hard whilst running a corner at a steep angle of lean, provided one keeps the throttle on to stop the bike standing upright. The low centre of gravity helps markedly.

Coming back to Melbourne was much easier all round — warm, lazy weather and steady cruise. Almost fall-asleep weather. There were lines of trucks along the Hume, a real what-am-I-doing-here on this “highway” scene. The heat picked up during the day. At Yass a BM R100S was heading for Canberra The WA plates showed signs of travel. The guy had disconnected his sidecar and was off to a funeral of a rider killed by a “Did Not See Him” driver in Canberra two days prior.

From Sydney to Yass I saw six patrol cars. Things did not look good on that slick, melted tar, dual highway but the bike retained responsive comfort and steadiness with fourth and top gear use all day at cruise speeds. Runs of around 260 km were fine on one tank.

At Benalla there were a couple of bikes running north, one a BM R90. Despite the heat the rider and pillion had their mandatory Belstaffs (Why is it all BM riders have to wear Belstaffs?). Homewards from Tassie. Lost their names in the book coming home. BM riders always wave to each other. It is a select band. But they must wave a lot because there are many out there movin’.

A couple of friends rocked into the Ivanhoe pad when I returned, having travelled 80,000 km around Australia in their trick Toyota in the past 10 months (with two rug rats ‘n all). They reported that anyone riding around the land without a BMW must feel sort of out of it as the roads are full of BM travellers.

Which brings me to the reputation. Is it deserved? Is it the best touring bike?

Well, we know there are many warranty claims on the BMs. BUT the warranty is a full 12 months with UNLIMITED distance. The Guzzi, like the Triumph, follows the Japanese warranty of six months/10,000 km.

The company has explicit faith in its product. Sure, owners of BMs are known for their pedantics, perhaps even operating beyond reasonable expectation and claiming many things on warranty which other bike owners would let pass. But one can also see that many claims would come from riders covering severe around Australia tripping and Let’s Go To The Rally The Hard Way, which must place great strain on all machines.

Great expectations are merely a consequence of the legend of BMs. I also know that the many high mileage BMW riders around don’t worry about the bike letting them down. Sure, a CDI system would be a nice touch for the cost of the bike and adjustable front forks for laden riding in the outback, but the bike was not designed for the tough Australian roads (What bike was?) where it not only survives, but excels.

The funny thing is that, despite the legend, I was not rapt in·the BM. However, the longer I rode it, the more the BM felt right, the more it did things which I found held the balance between riding sanity and reliability. And most of all, comfort and a sense of satisfaction. I don’t think I spent long enough with the RS and I’d like to do a rally run to really get the mood.

An R100S won the Castrol Six-Hour. It covers ground better than most bikes and it carries the rider and pillion in loping comfort most times. The price of $6200 for the R100RS, super-coloured, cast wheels and such, is high – too high in my opinion. But since when has that stopped people buying? Look at Harley and Triumph sales.

It is a matter of what you want. And the BMW seems to have plenty of magic to keep right on as the ultimate all round motorcycle.

By Kel Wearne. Two Wheels, July 1979

Geoff Hall: Boxing On. The 1986-1992 Model

To be honest, I’ve never been a big fan of the R100RS, mainly because of its riding position. Still, I’ve indulged in some rapid motoring on the Boxer flagship on more than one occasion and know of dudes who blasted 4200km from Brisbane to Dumbleyung, WA, in less than 40 hours. The opportunity to open road the BM for 1000 km after a few hours work in Brisbane seemed an ideal first shot in a test of the new R100RS.

The new RS really only shares the model designation, capacity, fairing and gearbox with its predecessor, which was last manufactured in 1983. Some of the differences between the two models have been forced by legislation, others by fashion and genuine development. Step aboard the 1989 model and you still know it’s an R100RS because the old seating position remains; fire up the engine with the electric starter and ride it and the changes become apparent.

In my opinion, the strength of BMW R series motorcycles lies in their ability to cover long distances over rough and smooth roads with a minimum of trouble. The benefits to a rider/pillion should be comfort during the ride and arrival at their destination with enough spirit in their bodies to rage. With the low power outputs of Boxer engines it’s pointless to compare the R100RS with Japanese sports-touring machines. The current crop of 1000cc Japanese bikes have at least double the power and less weight than the RS. Unless it’s a bumpy outback road, don’t bother trying to run with them.

The 1000 km from Storey Bridge (Brisbane) to the Sydney Harbour Bridge took a few minutes under nine hours, including a charge down the Putty Road at night. There was time for a leak, a·pie and some photographic stops. During the trip the RS was operating at 2000 rpm below its redline with no apparent effort. Experience with an R80 indicates that the new RS will do that all day, every day, without fuss.

I remember Tony Hatton remarking that he rode a full Castrol Six Hour on an R75/5 changing gears at 500 rpm over the redline with no problems at all. In fact, he mused that you could probably do it for six months, with no ill effects.

There is no doubt that straight line speed and acceleration of the new RS are down on previous models. You can’t expect anything else when you decrease the carburettor inlet tract size, inlet valve size and compression ratio, and fit a more restrictive exhaust system. Apparently BMW have tried to compensate for these performance-robbing changes by doing extensive work on the exhaust collector box, revising the valve gear (as per the R80), altering the heads and changing the alloys used in the pistons.

This work appears to have been successful although the maximum torque is produced at much lower revs than the old RS and there is a drop off in the 4000 to 5500 rpm range before the engine regains some grunt. The sagging torque curve first became apparent when ULP engines were introduced; its profile is in marked contrast to the torque curves of the super grade models (see graph in the spex below).

Other engine modifications include redesigned crankcases which have greater volume than previous models and a redesigned crankshaft main seal should also minimise leakages in that area. Some of the older engines were prone to seat and gasket failure due to pressurisation of the crankcases. These changes should stop these minor problems.

The engine isn’t silky smooth at any speed, in fact up to 3000 rpm you can feel the distinctive thudding pulse of a big twin. During the test this never proved to be annoying — it simply stamped a mark of individuality on the machine. The vibration does adversely affect the rear view mirrors and instruments. The clutch has a light lever action, although it rattles disconcertingly when disengaged. This year’s gearbox is like all the old ones — slow changing, notchy, but relatively reliable.

The new RS motor pulls hard from 3000 rpm (80 km/h in top) which is handy for overtaking slow moving semi-trailers.

However, between 110 and 150 km/h the power output goes to sleep for a while before regaining its grunt at 5500 rpm. As a result you have to pre-plan overtaking manoeuvres more carefully and just occasionally it was necessary to change down to fourth to maintain cruising speeds. The change in the torque characteristics isn’t a serious fault, but it is annoying at times, especially when you consider the strengths of previous models. Top speed has decreased by 15 km/h over older models, which may have some relevance on the Nullabor, but is of little consequence elsewhere.

One disappointment of recent Boxer engines has been fuel consumption. During my long trips it was difficult to run more than 210 km before switching to reserve. Range from the 22 litre tank is, on that basis, 250 km. Even at legal speeds, consumption was 15 km/l. The old RS would run 300 km on a 24 litre tank — a respectable distance at high cruising speeds. In fact, there would have been one less fuel stop if I’d taken the old model on a similar sprint.

Although it’s lost a bit of its speed, the RS appears to have retained its handling abilities. Once you get the hang of riding BMW’s patented rise and fall rear suspension, it is possible to travel pretty quickly on bumpy roads and through tight corners.

The 1989 R100RS has the same chassis as the R80 which was released in 1985. As an owner of an R80, I have always thought that there were deficiencies in the road going monolever set up and the K series forks. The front end of the R80 will shake its head over bumpy roads and the rear suspension appears to react poorly to small bumps which are close together. The twin shock RS used to wobble and weave on bumpy roads but didn’t try to pitch you out of your seat. The plush, long travel front suspension rarely became unsettled by broken surfaces.

The run through the Putty Road certainly tested the new RS over some poor surfaces and brought out some interesting results. The bike refused to display front end instability, although the front suspension appeared to bottom out on some large holes. It seems as though the change in weight distribution — 44/56 (front to rear) compared with 42/58 distribution of the R80 — and the down draft effect of the aerodynamic fairing may have cured the front instability problem. Some wobbles may still occur when the bike is fitted with fully loaded panniers. Unfortunately, we didn’t have an opportunity to test the RS under these conditions.

On the debut ride, the rear suspension pig rooted like a startled horse when the bike was ridden fast over bumpy surfaces. While I wouldn’t consider this dangerous in any way, it could be disconcerting to some riders.

However, corners with relatively smooth surfaces could be approached with absolute confidence. The RS would track through this type of country like a roller coaster. It was possible to accelerate through the apex of the curve and jump the BM out onto the next straight.

Despite clearance being restricted by the sidestand and the engine protection bars, it is possible to set a respectable pace on a winding road. The new TKV Continental tyres provide excellent grip. You will be blitzed by the latest whizz bangs on short scratcher’s rides, but the difference at the end of a long day’s haul will be negligible. Certainly on tight sections, where manoeuvrability is king, the R100RS will give little away.

When it became time to try the bike on dirt roads, I did so with some caution. After all, narrow, swept back handlebars aren’t conducive to good control when the front wheel decides to try and dictate where it will point in soft gravel. Surprisingly the RS proved to be a handy dirt road tourer with its limits more likely to be its lack of steering lock than anything else. It was a simple matter of bracing the arms whenever the going became tough, just to make sure you headed off any bid for freedom that the handlebars may have had in mind. You’ll need to be careful on outback roads as the alloy wheels will almost certainly bend if you don’t look after them. However, that’s a compromise you will have to live with because fashion is fashion, even if it doesn’t make sense.

BMW has never provided outstanding brakes, so it’s not surprising that the RS is fitted with standard K series twin discs at the front and a drum brake at the rear. Brembo calipers, sinter pads and stainless steel rotors combine to give a vague/hard feel to the front brake lever. While performance is better than adequate, it is not up to the standard of the best sports machines. The rear drum brake provides better feel and stopping power than the rear disc found on the 1983 RS. You will not win any braking duels, however faced with real life obstacles like ‘roos and stock, you will have a better than even chance of pulling up in time.

With regard to the ancillary equipment, nothing has changed. The switchgear is the standard R series fare, available since 1981. It works quite well, although the placement of the horn button high on the left hand block above the high beam dipper and blinker toggle makes access difficult.

Separate tachometer and speedometer nestle either side of a panel of idiot lights, while a clock and voltmeter sit in the dashboard below the fairing screen. Vibration sets the instruments shaking at low engine speeds, but disappears at highway speeds. The rear view mirrors suffer from a similar problem, while giving you a look at your armpits and small sections of the road behind you. If they were a couple of centimetres further out from the fairing they would provide much better rear vision.

Rider comfort at slow speeds is not brilliant as the height relationship between the seat and the handlebars forces you to rest quite a lot of your body weight on your hands. By Ipswich, I had sore wrists and was suffering from an illusion that I was constantly riding down a hill. Perhaps a little more preload on the front fork springs would change this — if only they were adjustable! On the positive side, there is enough wind flow around the fairing to take some of the weight off the wrists at touring speeds. By the end of the trip — and more importantly, next day — my wrists were ache free.

The RS fairing was a trend setter when it appeared in 1978 and despite the age of its design, provides some of the best protection about. An average sized rider (175 cm) is well protected from the elements providing they do not stop during rain. Taller riders will bang their knees on the fairing and catch quite a lot of the airflow going over the screen. The effect of this buffeting will largely depend on which brand of helmet you are wearing. Suffice to say it can create noise and helmet lift problems.

There are some negative aspects to the fairing, centring on the way in which it traps engine heat. Low speeds, hot days and a lack of proper protective clothing will leave you with steamed feet. At speeds over 100 km/h the problem disappears. If you are trudging along at slow speeds, you will be able to feel the heat being radiated by the engine. Despite my reservations, I still believe that the RS’s fairing is one of the best around. At the end of 1000 km I still felt good and my leathers were remarkably clean, all courtesy of the fairing.

Underneath the seat of the RS is the usual high quality toolkit, puncture repair kit and comprehensive owner’s manual. The two storage compartments are useful for storing spare bulbs, lightweight weather gear and other small odds and sods. Lock the seat and you have secured the goodies and your helmet if you have used one of the hooks provided on the subframe. One small drawback is the lack of any ocky strap hooks, until pannier frames are fitted to the bike. Without these it is hard to attach a touring bag securely. There are seat hinges and holes which can be used for straps, but they are so far under the seat that it’s almost inevitable that you will damage the surround if you use them. It’s a pity that a little extra thought hasn’t been put into this area. Still, there’s an auxiliary power outlet on the left hand subframe from which you can run all sorts of fancy gadgets.

As part of the model update, BMW have established a policy of fitting 30 amp hour batteries as standard to the R100RS. They have also changed the charging characteristics of the alternator so that it operates from 850 rpm, as opposed to more like 2000 rpm on the old models. It’s certainly noticeable that the voltmeter needle remained on 14 volts almost continuously even when the bike was used for commuting. The gearing on the starter motor has altered so that it spins the engine faster, saving the battery further. Let’s hope that we have seen the end of short life BMW batteries.

On the whole, the paint work on the RS was of a high standard. At this stage it is only available in iridescent pearl white with three-tone blue graphics. This is offset by black wheels with polished alloy highlights. Personally I think it looks good, although some people reckoned it looked too flashy for a BMW. Just wait until they see a Kl! Lots of people commented on the bike, stopping to ask questions such as: “Is it as good as· the old one?” (Yes) or saying: “Gee you kept that in good nick.” The classic lines of the Boxer caught the attention of the general public to the extent that some commented favourably at the traffic lights. It seems that the design continues to hide its age extremely well.

Unfortunately, the quality of fit between the screen and the fairing was poor and white paint had flowed onto the black inner surfaces.

The new BM is a sensible bike which isn’t joining the horsepower race. It’s a practical, easy to work on, pleasant to ride machine which should provide you with many trouble-free kilometres in its updated format. At $11,500 plus on road costs, the R100RS sits in the middle of the BMW price range which spans the R80 ($7990) to the K100LT at·$16,550. However, it is considerably less expensive than its K series compatriot, the K100RS, at $13,150.

By Geoff Hall. Two Wheels, August 1989

Falloon: The Classic View

When BMW released their ground breaking R90S more than forty years ago it changed the popular perception that BMW motorcycles were staid, stodgy, and only suitable for wealthy geriatrics. Hans Muth created a styling masterpiece, and the R90S was a real Superbike.

Yet while swift and comfortable, it came in for some criticism regarding high-speed stability and only offered minimal weather protection. The high steering inertia of the handlebar-mounted fairing accentuated this instability and a year or so later Muth was asked to create a new motorcycle with a more integrated aerodynamic fairing. The result was the R100RS, arguably even more significant to BMW than the R90S.

Underneath the large fibreglass fairing was also the most powerful incarnation of the boxer yet, and the R100RS created a sensation when it was released at the Cologne Show towards the end of 1976.

The R100RS was the first motorcycle to incorporate a fairing providing rider protection, aerodynamic function, and motorcycle stability. The nine-piece fairing design was so advanced that it still continues as a benchmark in motorcycle fairing efficiency, and few later examples can match it.

But there was more to the R100RS than an efficient fairing. The engine was bored to 94 mm to provide 980 cc, and with larger valves, the power went up to 70 horsepower at 7250 rpm. Instead of the concentric Dell’Orto carburettors of the R90S, the R100RS received Bing 40 mm constant-vacuum carburettors. Although the frame and swingarm were essentially unchanged, a second transverse tube was added between the front double downtubes and the frame tubing was a thicker section.

Despite these welcome improvements, the front fork still included the weak pressed steel upper triple clamp, and the rear subframe was bolted on as before. Most early R100RSs were fitted with spoked wheels, with a drum rear brake, but from 1978, all came with snowflake cast alloy wheels with a rear disc brake.

If the R90S stretched the sporting boundaries with its low handlebar and semi-racer riding position, the R100RS took this a step further. The narrow, clip-on style handlebar fitted inside the fairing, and provided a surprisingly aggressive riding position. Considerable weight was placed on the wrists, encouraging high-speed touring. There was also the choice of a standard dual, or sporting solo, almost one and a half, seat.

Updates to the R100RS came almost annually through until arguably the finest model, the 1981-84 series. For 1979, the camshaft drive was completely revised, an automotive-style rotary contact breaker ignition fitted along with an oil cooler, and torsional vibration damper added to the driveshaft. Most development was saved for the 1981 model. This year saw Galnikal cylinders, electronic ignition, a plastic airbox with flat air filter, a much lighter flywheel and clutch assembly, and superior Brembo front brakes. The front brake master cylinder also was moved from underneath the fuel tank to the handlebar.

The R100RS was one of the most expensive motorcycles available in the late 1970s and early 1980s. And despite retaining a relatively unsophisticated engine, it could still match any other sport-touring motorcycle, even its replacement, the four-cylinder K100RS.

The weight was a moderate 210 kg, and the combination of a large 24-litre fuel tank, long travel suspension and enveloping fairing made it an incomparable road burner. Even today an R100RS is a highly competent sport touring motorcycle, one eminently suited to potholed modern highways if not over enforced speed limits. While the K100 has vanished into obscurity, the R100RS was another BMW masterpiece. Easy to maintain and reliable, the R100RS is a bargain classic.

Five Things You Didn’t Know About The R100RS

1. RS stood for Rennsport, and was intentionally used to create an association with the magnificent double overhead camshaft RS54 racers of 1954.

2. Hans A Muth and Günther von der Marwitz hired the Pininfarina wind tunnel in Italy (pictured above) for the development of the R100RS fairing. It cost BMW $7000 a day, a substantial sum in 1976.

3. The RS fairing was claimed to reduce front wheel lift by 17.4 percent, drag by 5.4 percent, and the yawing moment in side winds by 60 percent. All this, with a weight penalty of only 9.5 kg.

4. In October 1979, an R100RS was prepared for an attempt on a series of long distance records. At Nardo in Italy, a team of four riders (Dähne, Cosutti, Milan and Zanini) set five new world records, including an average speed of 220.711 km/h over 100 kilometres.

5. Although the K100RS was intended to replace the R100RS from 1984, public demand saw it return only two years later. The resurrected R100RS ran through until 1992.

By Ian Falloon

Ian Falloon has written the definitive model by model history of BMW, The Complete Book of BMW Motorcycles. Superbly illustrated with factory images, some of which Ian supplied for this test, and with every model covered in detail, it’s priced at $80 and available direct from Ian here.