1973 Suzuki GT250 vs Yamaha RD250

Yamaha or Suzuki? It was the burning question on many a young dude’s mind in 1973, and it took Australia’s most comprehensive road test to pick the best 250 stroker.

Meet the Japanese 250 twins. And don’t underestimate them.

Both are outstandingly popular in their class, and despite visibly different exteriors both perform their jobs in surprisingly similar style.

Of course they grew up together, the RD and GT250. Both are the result of years of development, and their designs, like their prices, are very similar.

But their parents are locked in competition and racetrack hostilities are a frequent occurrence.

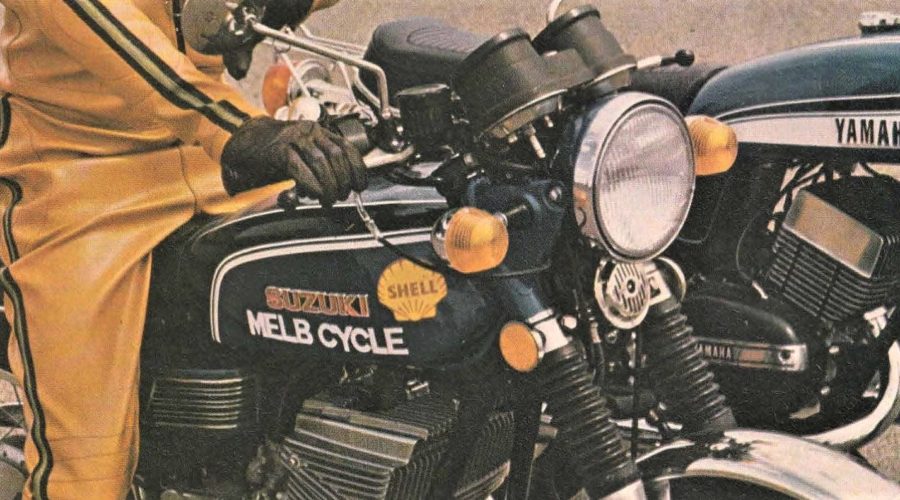

Traditionally it’s been the GT from Suzuki that’s come out best in such encounters. Our test model, from Melbourne Motorcycle Company, Victorian Suzuki distributors, was from the best-known production clash – the Castrol Six Hour. Ridden by Graeme Laing and Eddie Catton, it finished second in class and had competed in many races since.

Without getting too far off the test, we’d like to tell you what a competition-oriented mob the chaps at Melbourne Motorcycles are. Graeme and Eddie are manager and workshop foreman, and they’re out racing nearly every weekend. Just about everyone we spoke to was part of the Suzuki racing effort. If they weren’t riders they drove the ute, or manned the pit signals, or simply stayed back after work to prepare the bikes.

Anyway, our test Suzi had 1000 miles up, most of which had been done at racing speeds. Eddie seemed surprised when we voiced our concern about its chances in a direct comparison. (Yes, we told both suppliers their bikes were “going through the hoop”).

We’re assured the motor has not demanded a new part in its racing career and had not been pulled right down since the Six Hour.

That particular event saw the other 250 – the Yamaha – come out best, but at a production event at Phillip Island a short time before we picked up the Suzuki our test machine was a winner.

The bike was actually the Japanese home market model with a km/h speedo and an abundance of Nipponese writing, but other than that, identical to the bike sold on export markets.

The Yamaha, supplied by Milledge Brothers, was a “less exercised” machine. It had only several hundred miles on the clock, those put up by company mechanics careful to take things easy.

The RD250 ride was of great interest to us because we weren’t long off the 350 version which we thought preferable to a somewhat disappointing 350 four-pot Honda. It had been more than 18 months since we’d looked at a 250 Suzuki and in that time the bike has amassed its string of production race victories.

For three weeks both bikes went everywhere together and were put to exactly the same amount of work. They were ridden along highways side-by-side, trickled through the traffic together and subjected to the same tests on both circuit and strip. Only the riders were alternated.

Engines

A look at the specifications will show both motors as being 54 x 54 mm, 247 cc strokers. Though the Suzuki design is older it has proved an excellent long-term, high performer but the Yamaha can boast an unprecedented amount of world class road racing victories.

The bottom ends and piston dimensions are identical but the Suzuki has a slightly higher compression ratio, and the Yamaha a greater number of ports. The RD250 has 2 mm larger carbs and they are mounted on reed valves (sales term: Torque Induction).

Lubrication is totally different. The Suzuki has an oil pump driven off the gearbox (pull the clutch, blip the throttle and hey presto – no oil) and is injected to the cylinder and the main bearings. The Yamaha uses a crankshaft mounted pump that injects the oil at the inlet ports. Past experience has shown both systems to be satisfactory.

On the left hand side of both motors are two sets of contact points which, with the battery and coils, provide the sparks.

Even with the ’73 shape inverted scoop screwed on to the cylinder head fins the Suzuki engine does not look as attractive as the matt black Yamaha unit. Presumably this is because the former is an older design and has not had the styling treatment of the ’70s. It came out in the mid ’60s, remember.

Why ram air? A blast of cool air on the combustion chamber has shown on dynomometers to give a more stable torque reading when the engine is working under load and becoming very hot. Also the two scoop castings are the cheapest and simplest way of updating the motor’s looks.

On paper Suzuki claims to be developing two more ft/lbs of torque and one more bhp lower down than the Yamaha, but there’s no evidence of this in road performance.

Nothing separates the primary drives or the clutches of the two bikes.

The RD250 not only has lower overall gearing but a better spread of ratios. A 24:1 first is far better than Suzuki’s 20.8:1 in traffic and the slightly higher (0.5:1) top means a loss of only a few hundred rpm. But the last six years has shown the Suzuki’s gearbox to be reliable and long-lasting, and only time will tell for the other.

Frames

Yamaha has our vote here. Their tubular structure is well triangulated and finished whereas the Suzuki (an older design) lacks the diagonal from the swinging arm pivot point up at 45 degrees to the steering head.

Suspensions

Yamaha has fitted the kind of forks they have been fitting for nearly a decade. To call them poorly damped is an understatement. Any gain the bike could possibly have from the rigidity of the frame is thrown away by their soft springs, which, combined with light damping, offer a “sea trip” over heavy undulations. We can only guess that their development was done on roads as smooth as glass.

The Suzuki setup is a notable contrast. When we tested the 550 triple last year we expressed our appreciation of the fitting of a 750 front end. The same practice has gone into the GT250 which has the GT380 forks and brake. This means the front end is completely understressed and can handle any situation with ease.

Not much separates either bikes’ back suspension, but a bit of progressive coil winding for each spring would greatly improve both bikes!

Brakes

The big difference here is the disc fitted to the Suzi. The Yamaha distributors expected their 250 to turn up with a similar stopper but when they opened the crates, lo and behold, it was the same old drum.

Both back brakes are indistinguishable in their power, lock-free and fade characteristics but a great deal separates the front ends. The RD250 has a soft lining while the GT250 has hard pads.

On the road this means the drum is quick and easy to bite but also quick to fade while the disc requires a fair pull for relatively lock-free progressive power. Add to that the fact that the Suzuki’s handlebar lever applies pressure in the first quarter inch of movement and the Yamaha setup works out most comfortable around town.

Fittings

First of all the paradox. The RD250 has a small petrol tank with a large oil tank and the GT250 has a big petrol tank with a small oil tank – weird! On test very little separated their oil consumption – just a few percent in favour of the Yamaha, as with the mpg figures.

While the Yamaha has a beautiful instrument panel in comparison to the Suzuki, its inaccuracy (although perhaps more a problem on test than in normal road use) is disappointing. The last few Yamahas we have tested (TX650, RD350 and TX750) have all been around 10 percent over actual. Although the Suzi dial is a little harder to read it is only a couple of percent out.

The GT has warning lights for neutral, main beam and flashers, and the RD has a well laid out left and right flasher, neutral, main beam and stop lamp. Unfortunately the tail lamp does not light from the front brake on the Suzuki.

The one key locks the Yamaha ignition, steering, seat and petrol cap with ease. The Suzi does not have a swivelling seat (no helmet locks) and the petrol cap on our test model took a bit of a fiddle with the key.

Other notable points are the one-piece exhaust on the GT (very expensive to replace), the lack of a steering damper (though our test showed one to be unnecessary) and the weak, tinny horn. The Yamaha boasts a carrier and an oil tank dipstick but no vacuum fuel tap like the Suzuki.

On the Road

While the bikes start effortlessly from either hot or cold the left-sided lever on the Suzi is more awkward than that of its right-sided counterpart. Both engines can be kicked-up in gear by merely pulling in the clutch lever.

From the first time we sat on the Suzuki to the time when the machines were handed back it always proved the more comfortable. Not only is the seat softer and wider, but with less engine revs necessary the whole bike seems bigger – more like a 500 in the riding position compared to the RD250, which actually feels like a lightweight.

Suzuki’s GT has heavier steering in comparison to the rather loose feel of the Yamaha and the RD does not have to be rocked along on the gear pedal to quite the same extent. The Yamaha has swivelling rubber-mounted footpegs but they do not help the cornering situation; the exhausts ground early due to the weak suspension movement. Another criticism of the RD is the loud exhaust note – all these factors go towards making the bike the less comfortable of the two, and it’s noticeable on a long hard run.

The reed-valve equipped Yamaha is the more torquey of the two. The lower gears also help to the extent that at 35 mph in 6th the Suzuki is at 2500 rpm while the Yamaha is sitting on the edge of its powerband at 3000.

Although both motors begin to work at 3000 and only really start to come in at 4500, undoubtedly the Yamaha comes in earlier with a lot more and completely denies the “more power at less revs” claim of the Suzuki.

So you’re wondering how the GT has the best acceleration times? When the Suzi does come on song, closer gear ratios keep the power on.

Both gearboxes performed well on test but the RD did have a tendency to find a false neutral between fourth and fifth.

At night

We do not often conduct part of a road test at night but since this article, like a good hamburger, has to include “the lot” we spent three summer evenings and one night (all night!) riding the bikes around.

A quick look at the specifications shows both models to have the same lighting power but on test we found differences. While the main beams similarly point a slim concentration of light down the road with a useless 180-degree secondary illumination sweep, the dip beams differed greatly.

The Suzuki offers a strong and practical dip, the Yamaha equivalent is only there as decoration and is no real aid to night riding. Only the half-inch larger diameter size of the GT250 headlamp separates the two in physical properties.

Eight watt globes work both tail lamps but the Suzi has a lens twice the size of its opponent and an efficient design that loses none of the brightness, so the GT also has our vote on the back end. A carrier rack protects the Yamaha lens from damage.

Though the instruments are lit with the same wattage globes, the RD250 has a green filter which makes the dials very much easier to read.

On the track

Venue: Calder Raceway.

Both bikes bumped off easily in second gear with the lower ratio and better torque of the Yamaha giving it the edge away. By the end of the straight the Suzuki had caught up and it was neck and neck into Repco with the cold RD front drum working well.

Scrape for scrape around the big right hander the better handling of the GT had the edge, and since the exit surface is a little bumpy, the Yamaha gave a bit of a shake and took second place down the back straight. As the Suzi had come clean out of the bend its acceleration was smooth, while the RD rider fought that bit harder to keep his bike on line.

Through the right-left-right esses there was nothing to separate them as the Suzuki has good handling and the Yamaha effortless “chuckaroundability” (on the smooth). Down the main straight for the first time the positions remained unchanged with the GT having a slight edge on acceleration.

Leaving the braking to the last at nearly 90 mph the Yamaha had the edge with the instant power of the soft-lined drum brake paying off and with taking an inside line the positions were changed. The remainder of the next lap went by much as the previous one but on following braking session the drum brake just got that bit too hot, let the bike run wide around the bend and the Suzuki was back in front.

Riders were swapped regularly but the pattern remained unchanged.

But on the other hand it took just a slight mistake by the GT rider to let the RD through. The power band controlled with the reed valves is far easier to ride and means instant torque for instant acceleration while the other bike has to work hard for the same result.

On the Dragstrip

As always, this test was left to the last because of the amount of punishment it inflicts.

With a better torque spread, lower gearing and lighter weight, the Yamaha was first off the line every time. The bike seemed to just flick away effortlessly as the clutch take up made rear wheelspin or front wheel lift unnecessary.

This advantage the RD held until fourth gear was engaged ( at 50 mph) when the GT had overcome its higher gearing and the little bit began to show through. By the time the bikes hit 60 the Suzi had a couple of lengths lead which it easily held on every run until the 440 yards had been covered.

Maximum indicated speeds in gears for the Yamaha (at 8500 rpm redline) are 30, 42, 55, 72, 85 and 98 mph. That’s on the speedo; knock off around 10 percent for a true figure. The Suzuki, at 8000 rpm, runs 31, 44, 51, 50, 81 and 94 mph with only a two percent inaccuracy.

Another test on the drag strip revealed the pros and cons of drum versus disc under hard use.

Each bike was ridden hard up to 80 mph when the acceleration levelled out and they just rode along together for a few seconds. Upon a signal both riders went for their brakes hard and squealed to a standstill.

With its soft linings the Yamaha had the initial gain as the forks slammed down and the bike slowed dramatically to 50 mph. The disc took a fraction longer to bite, but it did so progressively and predictably. At 40 mph the Suzuki caught up (or is it slowed up?) and they were neck and neck. The last 40 feet saw the drum build up a bit too much heat and overtake the GT to run on an extra 10 feet.

Repeated four times in quick succession (they turned around after two stops) the tables turned completely in favour of the disc as the drum faded badly after two of the brutal stops and went away nearly completely on the fourth.

Comparison

There you have it. Our tests show that any one bike is not a clear winner in all departments. Our team’s opinion went along the lines that a Yamaha engine and frame with the Suzuki bits might make a great 250, but leaving it at that is no help to the buyer.

Though both machines are good in their own way they both have their individual faults and good points, so how do we summarise the torquey but bouncy Yamaha against the stable but less flexible Suzi? It is not sufficient to say the RD is better around town and the GT on the tracks and highways. In any contest there has to be a winner.

Without repeating a lot that has already been said, our overall choice was the Suzuki GT250. Other than the factual reasons, that was the bike our team enjoyed riding most.

By Derek Pickard. Two Wheels, April 1973.

Guido from AllMoto has collected a few period brochures for the Yamaha RD range here.