1972-1992 Harley-Davidson Sportster

Back in the early Fifties, Harley Davidson was in a quandary. Which is very much like a quarry since they both involve being stuck down a hole.

The Pommies, whose economy was displaying the severe detrimental consequences of finishing in a victorious position in a certain global conflict (WWII…The Big One) were producing some very rapid motorcycles, including the interesting International and Turner’s tuned-in twin.

These machines were capturing a sizeable portion of H-D’s market since they were winning quite a few of the prestigious US races — and this despite the American Motorcycle Association’s then current racing rules. These rules operated under the America’s Cup Principle and stated that while Pommie machines were restricted to a capacity of 500 cm3, the Yanks could run 750s. Various other factors were involved but it still meant that the factory H-D riders enjoyed a considerable advantage. The Brits kept on winning however; especially Francis Beart’s Nortons.

Now, Harley Davidson has always been a company which does not accept circumstances while in the prone position and tends to fight back, albeit in a manner which occasionally seems considerably less than egalitarian. Harley decided to produce a motorcycle to defeat the Poms on their own territory and, with the Poms taking the step up in capacity from 500 to 650 with bikes like Triumph’s T110, H-D also decided that “bigger is better” and the 883 cm3 K Series was born.

Despite styling with a distinctly British accent, the new model was still most assuredly a Harley-Davidson, a fact obvious from one look at the hugely-finned alloy side-valve V-twin engine. Bigger physically than a T110 (but not by much), it had the sort of style and performance which almost guaranteed it a place in the US market among American lovers of sporty machines.

The K series was further developed into the 883 cm3 iron engined, ohv X series in 1957. The first model, the XL, was the first Harley to bear the Sportster name. It had the performance to cause a sensation among American sports bike freaks, and the engine (intentionally) bore a striking resemblance to J. A. Prestwich’s mighty 1000 cm3 V-twin, the engine that powered many land speed record holding motorcycles.

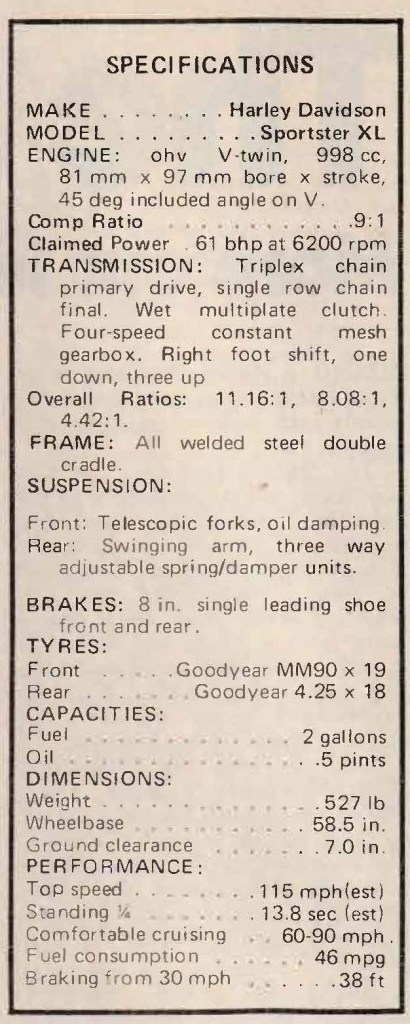

In 1972 the Sportster was expanded to a full 998 cm3 and continual refinement saw the original Sportster concept bear fruit finally as the awesomely powerful XR, a machine which, most regrettably, will never grace the shores of Dear Old Oz.

Now we have come another step in the development of the Sportster with the release of Harley-Davidson’s 1986 Evolution model. H-D has decided that a “back to basics” approach is what’s needed to lure the faithful back to the fold.

Enter the 883 (the real capacity of the original 900 K series) Evolution Sportster, a machine which is attempting to fill the original design parameters of the first model: i.e. it’s low, mean and cheap. A “Top Of The Line” 1100 cm3 version will also be available.

Enough preamble though, because my aim at this point is to compare for you the 1985 998 cm3 XLH and the new 883 Evolution model, both of which I recently had the distinct pleasure of spending a few days upon while punting about the countryside.

The XLH was a low mileage used machine which was well run in with approximately 6000 km on the clock and had obviously been very well maintained. The Evolution model was a brand spankin’ newie with a mere 700 km up and, naturally, its engine and transmission were still extremely tight. With that in mind let’s get into it.

Both machines share many chassis components. There are some differences, mainly due to the need for differing methods of support for the top ends of the different engines. The iron engine requires massive head steadies for both heads while the 883’s engine requires, apparently, a little less support for the rear head.

I wondered at the time whether the lack of support for the rear head would affect the frame’s rigidity on the 883 as compared to the XLH, since the iron engine is such a substantial and integral part of the chassis — being, as it is, bolted to the frame just about everywhere. I’m pleased to say that there’s nothing to worry about in this regard. The frame of the 883 is as rigid as the Sydney Harbour Bridge and only marginally less massive.

While the H-D frames are rigid and of the correct design – and also despite the narrowness and low centre of gravity possessed by both Sportsters – they were both less than confidence-inspiring handlers. This was due to the overly soft suspension at both ends (the 883 bottoming on the softest setting solo at the merest appearance of a bump and the XLH bottoming on the firmest setting solo over surfaces which my 750 K2 laughs at) and a swinging arm which appears to be constructed of one-inch square section mild steel and will flex at the drop of a trouser.

Both machines require a rigid swinging arm, Fournales rear shocks, much stronger front suspension and more efficient front damping. I’d like to ride a machine with the power and feel of a Sportster and the handling of a Ducati. As Editor McKinnon stated, “You wouldn’t want the power of a 900SS and the handling of a Sportster.”

Talking of power, it is here that the major difference between the two H-Ds makes its presence felt. The 1000 possessed an ample quantity of torque, being able to pull away from rest using only its 1000 rpm idle. (Actually, this one idled a bit quick — 600 or 700 rpm is normal. In top (fourth) gear it would pull cleanly from 1500 rpm (about 47 km/h) up to its redline of 6200 rpm (about 190 km/h) given plenty of straight flat road. Cruising speeds of 120-140 km/h were no problem and left sufficient grunt in hand for safe overtaking.

At speeds over 120 km/h, however, the 1000 felt as if it was about to mechanically bundy off. Tappets were knocking, pistons were slapping, gears were whirring and, to make matters worse, there was no large fuel tank to mask the noise and lull you into a sense of security — false or otherwise.

The 883, au Cointreau, is a different proposition. I won’t go into the finer technical details here, but the new engine is manufactured to much closer tolerances than the iron motor. Because of this the engine makes much less mechanical racket than the iron motor, despite the fact that iron masks noise better than alloy. Smaller valves and hydraulic lifters also have their part to play in the reduction of racket. Because of the extra power available due to more precise engineering and manufacture, the boffins have considerably detuned this Sportster from the iron model. Torque seems down, and the engine, despite a willingness to rev, seemed to lack some of the push of the 1000. Perhaps when properly run in the engine will loosen sufficiently to rival its iron brother.

Did I like the new machine? That’s a hard one to answer. I enjoyed it solo (which is really what it’s designed for) and I’d really like to ride it again when it has a few more miles on the clock.

The 883 lacks the brute appearance of the old iron engine but should gain broader acceptance since the alloy motor is extremely well made and should prove most reliable. It looks like a modern design after all and, together with its relatively low price should attract some of the buyers of Japanese Harley clones.

I did like the 883, but I think that if I had $7000 I’d start looking around. Only a few days ago I saw a very nice K series model for $3000, and there’s a bloke just up the road who wants to sell his 1984 model XLX for $4500.

The old ones may Shake and Rattle, but Holy Hell, do they Roll.

By Peter Smith. Two Wheels, January 1986

1972 XL 998

Riding a Harley Sportster is an illuminating experience, and a few loosely-held beliefs go down the drain.

The first is that over the past few years, and particularly with the Sportster, America’s finest has become a whole lot more a European-type machine. This point of view is expounded more by non-enthusiasts who once had a mate with a WLA, and they still equate Harley with hand gearshifts and huge, sprung saddles, but some experienced riders also feel the essential character has been lost.

Have no fear, the “Bike That Made Milwaukee Famous” effect still comes through loud and strong; so much so that to the European or Japanese oriented rider the first few miles are compounded of exhilaration, fear, and doses of “Dammit! I don’t believe it! This can’t be happening.”

That’s the other important effect of riding the Sportster. Rides on Harley Davidsons come pretty rarely, even to road-testers, and the memory of what exactly makes the bikes what they are fades to a gentle blur.

Jump on one after a year or two away, and the first reaction is the same as a new chum. Then the memories start flooding back, and once again the Harley mystique, that combination of unfussed power, bulletproof engineering, and that horny masculine image grabs hold.

It needn’t necessarily make a convert out of you. In fact, a whole heap of the Sportster’s strongest features are drawbacks from a purist standpoint, but it leaves one with the profound feeling that there’s a bit more to motorcycling than can be contained in one man’s personal opinions. Sportster owners have a lot going for them, even if their mounts aren’t going to set the world on fire in road racing events.

And yet, paradoxically, a variation on the classic V-twin design, in the shape of the 750 alloy motor, has more than held its own against the world’s strongest road-racing machinery over the past year and the world’s quickest dragsters generally have a Sportster mill as a basis.

So where do you go from there? Well, for starters, you can take your hat off to a firm that knows enough about motorcycle engineering to build such a device, and enough about their riders to maintain the bike’s unique strong character.

And where they really score is in the visual effects department. How is slightly hard to tell at a searching glance. That much chrome just has to look bloody ‘orrible.

Plaster any other bike with the brightwork of the Sportster and you’ve got instant yuk, but on the big twin it looks just right, an opinion shared by boys (small and large), dogs, other motorcyclists, and good-looking chicks.

The first three categories of fan may seem relatively unimportant, although the phenomenon of dogs not rushing out to bite the riders’ ankles, but standing in awe, will lead to less of the celebrated falling-down disease, and merits careful consideration.

Backing up the effect of the chrome on the test bike (a 1972 model) was the eye-catching dark apple-green metalflake paintwork. Both glitter and paint are of a high standard, and contribute markedly to the overall looks.

There’s a few jarring notes in the tune, however. Like the frame casting, which is rough as bags around the steering head and rear damper mounts. Makes the he-man image just a bit boorish. Also, the tail light looks quite lost and undersized stuck on the back of the big deeply valenced rear guard, and the original joined together mufflers are severely restricting and sport some of the messiest seam welding since the early Hondas.

In general though the looks are great, in a purposeful rugged way. We especially liked the instrument binnacle mounted on the centre of the bars, the long slim forks, the seat/tank combo, the overall look of the huge powerplant, and the cowl over the headlight.

This cowl struck a rather incongruous note, being made of cast light alloy, as are the rear indicator outriggers and the grab rail. Apart from being more fracture prone the stuff is harder to put a polish on than chromed sheet or tube steel, which would also be less expensive to produce. Ah well, you can’t win ’em all.

The general shape of things from the rider’s point of view takes a bit of getting used to. Main offenders are the bars, mounted deep in rubber (for vibration reduction). This they do rather well, but they also have one heap of movement independent of the rest of the machine. Quite unnerving, as is the 527 lb dry weight, immediately apparent as one tries to wrestle it up off the side stand. No centre stand is provided, an understandable move, and the side unit, a plain curved bar, will burrow enthusiastically into even hard asphalt after a couple of hours. A piece of wood is a handy accessory to have around.

The final unnerving position is the shape of the bars: high, and pointed back like a wheelbarrow. It takes a while for the right wrist to get used to operating in a sideways arc instead of fore and aft. The minor controls are symmetrical side to side, with the starter button and indicator switches on the right, horn and high/dip on the left. The switches are of the small, square, up-down style. Okay in the case of the dip switch, but a definite no-no for the indicators.

Every fraction of a second spent fooling with vague indicator switches is a huge step nearer disaster in city traffic, although this one wasn’t as bad as some we’ve used, being mounted on the forward edge of the bar, and able to be operated by the thumb and forefinger wrapped right around.

Starting is an easy procedure, if you do it right, a bit of a drag if you fluff. The choke, a car style pull-knob located under the left side of the tank, works a car-style valve on the big Bendix carb, and needs about three-quarter operation for a cold start. Hit the starter button, and a whining groan proceeds from below, somewhat reminiscent of an old Mack truck.

The motor catches quickly, and it too is reminiscent of a Mack, but the trick lies in keeping it running. The choke must be returned as soon as the fires are lit, but not before. Miss either way, and a flooded motor is the price and you’ve got to wait.

The unit warms up quickly and when warm needs only a touch on the button to have things underway. With the electric starter as the only system on the bike for getting it going, fears could be held of flattening the battery, but it seems a remote possibility. The battery is truly huge, as are the generator and the starter itself.

To anyone brought up on high-revving two strokes the sound and feel of the motor must come as a real eye opener. It whiffles and snorts and clanks away in a style that’s peculiar only to V-twins.

The 45 degree angle between the pots gives 315 degrees and 405 degrees of crankshaft rotation between successive power strokes and leads to the offbeat stutter at idle.

Mechanical noise is there, but of the solid, purposeful kind. Everything sounds strong, and it is. The rear conrod is forked, with the front one fitting inside it on the crank pin; engine width is thus reduced to a minimum. Three roller bearings take care of the big ends, while the mains are also rollers, huge, and on the drive side, tapered for even more strength.

Primary drive is by a massive triplex chain via a wet multiplate clutch to the four-speed box. The transmission overall is a delight to use, and is obviously unfussed in handling the power. Clutch takeup at easy revs felt a little rough, but the unit operated firmly and precisely, and the lever pressure, though not as light as say a Honda 750, is still far from being impossible.

Operation of the right-hand mounted one down-three up shift lever proved to be a delight. Although lever travel is long, it’s also firm and absolutely precise. No way can you miss a shift unless you absolutely set about doing it.

The only complaints we had were a faint but persistent clack on the 3-4 shift and a reluctance to yield forth a neutral when stationary.

Under way it takes no time at all to adjust to the motor’s incredible low speed pulling power, acknowledged by all to be one of the Harley’s strongest points, particularly if most of your riding is done on two strokes.

By comparison to the average stroker, the Suzuki triples pull well down low, agreed? Hell, they’re positively screaming by comparison to the Sportster! With little more on the tacho than the maker’s name, the beast is pulling like a train and begging to have a crack at the nearest brick wall or similar vertical obstacle. Peak torque, a thumping 50-odd ft/lb, is developed in the low 2000s!

Sadly, it doesn’t stay that high as the revs rise and the impression of running out of puff is strong in the high 5000s.

The test machine was also afflicted with fuel feed troubles in the top range, and we weren’t able to give it flat-out or ¼ mile tests. The highest speed achieved was 98.9 mph.

Although the motor performs tirelessly, the low-down punch leads to relaxed riding and early gearchanges. The trap we consistently fell into though, was that of moving off fairly briskly, and then having the bottom fall out of the delivery when we changed into top, a consequence of the big gap between third and fourth. Harley could definitely put some work into closing the three lower ratios.

We wouldn’t want them to change the long cog though; it’s really long, at 17.4 mph/100 rpm, and the machine moves deceptively fast across the landscape with the motor seemingly at little more than an idle. On the open road, 80 is an all-day proposition.

There’s only one drawback to moving across the landscape on the Sportster — swiftly or not — and that’s what to do when elements appear to be on a collision course. Reach for the brakes, say you? Reach away; it’s marvellous for developing the right wrist, but wreaks untold damage on underpants, nerves, and the general health of the rider.

There’s nothing wrong basically with the 8 inch single leading shoe brakes on the Sportster. They’d probably tear the tyres off a 125, but they have no hope of hauling up nearly 700 lb of machine plus rider. Thirty-eight feet from 30 mph, with the rear brake only just starting to lock, is quite terrifying. And nothing’s more disappointing than to haul a heavy front lever into the bar and have nothing much more happening than the forks taking up full travel. Hope is at hand though, in the shape of the upcoming 1973 model, which sports a 10 inch Kelsey-Hayes disc up front.

The question of the front fork is another contentious one. In the currently modish Ceriani style, they are good-looking, if perhaps seeming a trifle slim for the job.

Asked the question under operating conditions, they are quite disappointing. Travel is too long, the springing too soft, and the rebound damping unable to cope with the heavy front wheel whizzing up and down.

Another unnerving phenomenon on the move is the action of the bars, with their rubber mounting giving so much play. Over those dreaded longitudinal gaps between concrete and bitumen that are a feature of so many Sydney roads, the bike behaves in a very stable manner, but the bars send up some quite frightening and inaccurate information.

Even worse is the sensation when cornering fast round a bend in a concrete road. The bumps over the joints will always sort out the quirks of a bike’s handling. In the Sportster’s case the forks start up a long slow oscillation, up and down, which sets the bars off from side to side. Once a good harmonic sets up, it proves too much for the swinging arm, which joins in the fun, making the end impression of being aboard the world’s fastest bowl of jelly.

And yet the bike does corner really well under the right circumstances. The long trail and fork rate, allied to the heavy weight, rule out quick peel-offs or sudden line changes, but on a smooth surface and a well set-up like the machine will hang in there until the left footrest loses rubber. And that’s one mighty long way over, so the machine can’t be written off as a pig of a handler. It’s really very good.

The huge 4.25 x 18 Goodyear rear tyre does its bit to add to straight line stability. In section it’s next best to square, and well cranked over one is aware of how little is the amount of rubber in contact with the deck.

Apart from the unusual bars the riding position is good. Footpegs are well-located, and an easy touring stance can be adopted. The handsome seat was disappointing, being too wide, and having a hard piping round the top edge. Under load the motor gives out a coarse vibration in the 3500-5000 rpm range, although this is vastly reduced while cruising at these speeds.

Still on the grumbles, the key is awkwardly positioned above the oil tank along the right hand edge of the seat, the lack of a tool kit and the bodgie steering lock — two holes that line up to slip a padlock through, with the padlock not supplied.

On the credit side are the magnificent engineering of the bike, faultless lighting and electrics (including a horn that’s able to blow a semi-trailer sideways across a whole traffic lane) and top-class paint and chrome.

Above all, the Sportster has that magical quality of presence, and a no-compromise character that one has to come to grips with. No product of intensive market research and design team cooperation, this bike, tailored to the average wants of the average rider. Instead, it is the machine for the rider who wants to stand apart, who is willing to take the good features and the bad. Expensive it certainly is, but for the right man the Sportster is good value, especially with the 1973 bonus of a front disc and beefed-up forks.

By Derek Pickard. Two Wheels, July 1973.

1986 XLH 883

In times gone by, the Harley-Davidson Sportster has projected the image of a raw and angry motorcycle. It may never have been King of the Superbikes, but in the late 1950s (it was introduced in 1957) and early Sixties it personified power and straight line acceleration.

When the British marques got their act together in the late Sixties the Harley had met its match in terms of speed, and the British also had the handling. When the Honda Four hit the streets it was game, set and match. The Japanese blaster simply left everything in its dust.

However, any machine which can survive 28 hard years of motorcycling history has to have something going for it, especially when you consider the changes which have occurred in this period.

Harley-Davidson’s 883 Evolution Sportster isn’t simply an updating exercise but a deliberate attempt to broaden the appeal of the machine. During the last five years the Japanese factories have made several determined attempts to steal parts of the traditional Harley market with numerous versions of V-twin powered look-alikes. Harley has now decided to fight back. Vaughan Beals (H-D President) makes no bones about it — the new Sportster has been designed as a straight-out attempt to keep the retail price down ($US3995) and lure buyers of the Japanese replicas and sports motorcycles to the fold.

Before the 883 hit the streets there were rumours of belt drive, five-speed gearboxes and rubber engine mounts, but these were all excluded on the grounds of reducing costs to an absolute minimum. Potential buyers shouldn’t be dismayed, however. Harley has included plenty of improvements without resorting to much of the technological gimmickry of its competitors.

Most of the updating has occurred in the engine department, where capacity has been reduced from the 998 cm3 of the 1000 XLH to 883 cm3 — the same as the original Sportster of 1957.

Gone is the cast iron motor. In its place, Harley has created an 883 cm3 45 degree V-twin based upon the original Evolution motor which debuted a couple of years ago on Harley’s 1340 cm3 models. The changes aren’t exactly revolutionary, but they are aimed at increasing the efficiency of the smaller motor. A much narrower included valve angle of 58 degrees is employed (90 degrees on the old Sportster), flat-top pistons are used (high-domed previously) and a shallow bath-tub combustion chamber promotes more efficient burning of the fuel mixture.

Cylinders and heads are aluminium alloy and weigh 3.5 kg less than the solid cast iron numbers on the old motors. The new alloy cylinders closely match piston thermal expansion rates, promoting better sealing, cooling and lubrication qualities.

Although this little motor is a full 115 cm3 smaller than the old one, there’s not much difference on the road. The head says that perhaps the “baby” Sportster has a bit more poke at the top end — probably because the new Evolution head can ingest more mixture at high revs — and a little less low down grunt.

A couple of things become abundantly clear when you start the 883 up. This H-D is quiet. In deference to the new US noise emission control laws, Harley has seen fit to do a bit of mechanical homework. The Sportster motor has always been a pretty noisy beast due to the fact that it has four separate camshafts and a total of five cam drive gears.

On the new model, the factory has helped the situation by fitting hydraulic lifters (as opposed to mechanical ones), but the most significant aid to noise reduction has been a new computer at the Milwaukee gear plant. Each cam gear and cover is matched by the computer to ensure that the mesh between the gears is within quite small tolerances. The result is a big reduction in the gear clatter department. Besides being relatively quiet, the Sportster motor has also lost a lot of its vibration, partly due to the refined gear set up and better breathing, but also due to a reduced reciprocating mass. Smaller diameter pistons, domeless crowns and shorter skirts means a significant reduction in weight. New two-step rocker covers (like the new 1340 engine) mean that all top-end/piston/cylinder overhaul work can be done with the motor still in the frame. Lubrication has been improved and to cater for the hydraulic lifters oil capacity is up 50 per cent. Oil is delivered to the engine via the filter and then returned to the oil tank.

The motor still shakes but it is noticeably smoother than its predecessor, and that’s an improvement that has been due for a long time. Don’t worry, Sportster fans; the motor still emits that Thunka, Thunka sound which is so characteristic of a Harley-Davidson. Although the vibration has been reduced considerably it hasn’t been eliminated altogether. You still know that there’s a big V-twin pounding away underneath the tank. Some sensations come through the footpegs and the handlebars but you get used to it. The mirrors blur up to about 100 km/h, but above that you can differentiate between a semi and a pushbike. Sitting at a traffic light the whole bike shakes. You watch in wonderment as the front wheels hops up and down on the spot. There’s a certain amount of class about that.

Overall, Harley has tightened up its manufacturing tolerances considerably. The direct result is a smoother, quieter engine which is a pleasure to sit astride. The key and choke control are just where you’d expect, on the left hand side half way along and below the tank. Give the motor a little bit of choke, hit the button and the electric starter will do the rest. If you leave the choke on for too long the engine will simply stop; it only likes so much chocolate!

Kick the bike into gear and you discover a smoother four-speed shifter than previously, courtesy of those better manufacturing techniques. The clutch isn’t hydraulic, as is so common these days, it’s cable operated.

Take up is nice and progressive … just feed the clutch in and let the torque of the engine take over. Once you get to 60 km/h in top the motor gets into its stride. It’s no rocketship; there’s just honest grunt punching you down the road in long strokes. Run the engine up, back off, and you get a fair smack of vibration for a second or two on the overrun.

Our particular Sportster wasn’t too keen on pulling away from anything less than about 40 km/h in top, but it never hesitated above that speed. The Sportster’s happy to putt down the highway at a steady 100 to 130 km/h. Sure, you can go faster, but at that speed everything is pretty cool and that’s what cruising’s about.

There’s a lot more to the 883 Sportster than the revamped motor. What makes this motorcycle stand out is its seemingly ageless good looks. In 1957 the original Sportster was born and in many ways the latest version is very similar. Simplicity and solid enginering are the benchmarks of Harley-Davidson’s philosophy. Both are amply demonstrated on the 883.

Your perspective of the world changes considerably when you lower yourself into that well-padded and shaped single seat. A small traditional Harley tank barely covers the tops of those seemingly massive rocker boxes. You sit low down, with the hands stretched up to the handlebars. The footpegs aren’t badly placed, but things would be much more comfortable with forward controls and highway pegs. Sitting high up above the small Bates-style headlight the speedometer looks lonely, a token gesture to the law which says you should know how fast the wind’s rushing by.

Nestling under the speedo are four idiot lights: high beam, neutral, turn and oil pressure. You can’t see them all that easily; perhaps it would have been better to leave them off altogether. Should you have cause to haul the H-D into line, there’s a wide, flat handlebar, curving slightly back towards you. Soft, fat grips reduce some of the vibration and provide you with a good fistful of control.

The machine rarely moves off line unless presented with a few sharp bumps in rapid succession. Then it reacts with a bit of a wallow due to the typically ineffective damping of the rear units.

The front suspension is double-acting hydraulic forks, with none of your fancy anti-dive or air pre-load. They work well enough providing you are prepared to take things easy. A rough road will send a few shocks back to the hands, but nothing too hard, and there’s a bit of fork flex if you try riding like a racer.

The twin cradle frame and rectangular section swinging arm are both mild steel numbers. In fairness they handle the job well enough, but a dry weight of 211 kg and the pretty ordinary rear shocks make their job difficult. Some would say, “Well at least there’s suspension,” and, in truth, the package survives well enough as long as you take your time. This machine just lets you know loud and clear when you’re going too fast – it simply gets out of shape and becomes uncomfortable. The Sportster is a cruiser, and it is determined to keep the action within its terms, not yours.

The long wheelbase makes cornering a precise task on the 883. You need to caress it through the turns with a good deal of patience. Encounter some rough stuff going too fast and the front gets light while the rear suspension will kick you hard in the bum. The machine will wallow and weave both fore and aft of the motor in these situations. I actually grazed a bit off the footpegs, but you miss the true point of the machine if you’re into that. Give the 883 its head on long gentle curves, slot it into top and let the big V-twin haul you along.

All the better if your lady is behind you perched on the narrow pad which doubles as a seat. She’ll be hanging onto you, cuddling, warm and close. (If she hasn’t already fallen off the back – Ed.)

A sunny day, a grassy bank and the Sportster cooling in the background. There are worse ways to spend your life.

The bike is a crowd stopper because it’s a blast from the past. Long, low and sparse, its looks can create a throng of admirers within minutes. Older gentlemen remarked on the wire spoked wheels and the sensible functional equipment. “How old is it mate?” was a common question, indicating that Harley has managed to maintain that 1957 image.

The plain switchgear covers the basics. You can hold the blinkers on manually for as long as you want, or lock on until you hit them again. The idea of a blinker switch on each Side took a short time to master, but after a while this system felt easier to use than a combination switch. The left handlebar has the dipswitch and horn button, while sturdy kill and starter buttons reside on the right handlebar. It’s good, functional, easy to use stuff.

The single disc brake at the front requires a massive heave on the lever to start biting, and its power feels woeful when compared with Japanese equivalents. At the rear, (again a single disc) it’s easy to make the tyre squeal, and in general the imbalance between the front and rear brakes and the wooden feel of both comes dangerously close to compromising safety in emergency situations.

The crazy thing is that nearly identical brakes have been fitted to other Harley’s Two Wheels has tested, and while they’ve never been the best in any department they have had much more power than those on the 883.

Owners of the 883 will probably want to stay fairly close to home. Should they venture forth into the back of beyond, some caution will be required. With only 8.5 litres in the tank you’ll be stranded after about 150 km. Harley-Davidson has always had a reputation for mechanical reliability and shown its confidence by supplying not even a solitary screwdriver. A check up is recommended every 8000 km (double the 998’s interval) and there should be little to do between times. Despite Harley’s confidence, we’d like a few tools just to act as a security blanket.

The remainder of the Sportster is just as solidly constructed as the engine. A massive locking sidestand provides support when it comes time to park the Harley. Blinkers are chromed steel, the hydraulic master cylinders are massive alloy affairs, while the mudguard brackets look strong enough to support the whole bike. Perhaps it’s a bit unnecessary, but then again it’s part of a very successful concept which simply refuses to die. There is one drawback with the quality of the alloy: in places it was being attacked by the atmosphere. You’ll have to provide a fair bit of tender loving care to keep the bike looking its best.

Harley-Davidson has installed a new electronic frame painting plant and the quality and durability of the finish confirms its efficiency. Our test machine had a blemish around the fuel filler but the remainder of the detailing was excellent.

The 883 should appeal to the traditional market in time, but there will also be more than a few buyers among the doctors, lawyers, stockbrokers and investment gurus of this world. The bike walks tall in the eyes of riders who demand a level of commitment to a design far greater than that shown in the “here today, gone tomorrow” philosophy incorporated in many machines. Buyers of the 883 can be confident in the fact that five years down the track they’ll still be able to get spares and, in the short term, their pride and joy won’t lose around 40 percent of its value when next year’s all-singing all-dancing new model comes along. Harley will be sticking with the 883 for many years to come.

In terms of value for money, you’ll notice that our spex column has two ratings. The lower rating indicates that for less money (although the gap between the 883 and the Japanese multis is considerably less than has previously been the case) most other makes will give you better performance and handling. The higher rating is recognition that, although 883 requires plenty of dollars up front, you’re likely to be far better off when selling time comes around because you won’t be staring a two or three thousand dollar loss in the face, a fact of life with many one and two year old bikes which are superseded often within a year of coming on to the market.

The 883 should win a lot of new customers for Harley. Perhaps many will still exclaim “Too much for not enough!” However, Harley is hoping that many more will go for the chance to grab a good, honest motorcycle which will go on being a good, honest motorcycle long after many of the race-replica style 1986 superbikes have faded away.

By Geoff Hall. Two Wheels, January 1986.

1986 XLH 1100

Anybody out there remember a late night TV show called “Then Came Bronson”?

It centred around this bloke (no idea what his first name was, if he had one), who had a mate commit suicide and leave him a motorbike in his will. Bronson at that time was a pretty straight sort of guy, holding down a big city, collar and tie job, but the opportunity was there so he chucked in the job and the condo and took off around the U.S.of A. to meet his destiny and lots of beautiful, randy, blonde women along the way. It was an enormously cool thing to do in 1969.

With hindsight, it’s no surprise that the bike his late mate left him was a Harley Davidson Sportster. Firstly, because Sportsters were around in 1969; secondly, because the Sportster was, and is, an enormously cool motorcycle; and finally, because the rider has to stop for petrol every time he gets it into top gear.

This provided ample opportunity for Bronson to meet his destiny, lots of beautiful, randy, blonde women, and whatever else it took to fill 60 minutes every Thursday night.

None of this is especially relevant, I guess, because your correspondent met his destiny the day after Playboy published its first-ever centrefold with pubic hair. In fact, the only beautiful, blonde woman I’ve ever had an encounter with was the first-ever Playboy centrefold with pubic hair. And besides, they didn’t have self-service petrol stations in 1969, did they.

It’s just not the same trying to chat up some bored country sheila imprisoned behind her cash register in the glass and plastic monuments that pass for “service stations” these days.

The grand-daddy of Australian ratbag bike journalists, Kel Wearne, once described riding a Harley Davidson as like having a removeable tattoo. When you’re astride a hog, you’re the best looking, toughest, meanest macho-biker on the Hume.

But when the world’s coolest motorbike is parked outside next to pump 13, sandwiched between 27 grotty Commodeodours packed with 27 mums, 27 dads and 81 sneering, snotty, Victorian schoolchildren, the aura is lost. The tattoo is removed, your balls are no bigger than anyone else’s, and a bloke is just pissing into the wind trying to crack on under these circumstances.

So much for dreams. This was one trip where a Harley Davidson would have to stand on its merits: 1200 kilometres (half of them in the rain, as it turned out) in two days, on a vibrating lump of a V-twin, with no fairing, high handlebars, and an 8.5 litre fuel tank. Fuel reserve was alleged to be a whopping 0.9 litres.

Unsure of fuel consumption, and petrified at the thought of pushing a 210 kg motorcycle packed for a weekend’s camping, I set out down the Hume Highway just as the weak winter sun was penetrating the Sydney smog. I filled up at Liverpool on Sydney’s southern edge, then topped up at Mittagong for the run through to Goulburn. This second section was done at a more relaxed pace, sitting on 110 km/h rather than 130 km/h, and fuel consumption improved from 17 km/l to just over 20 km/l.

Goulburn to Yass recorded 22 km/l, so I gambled on the 148 km stretch through to Tarcutta. At 138.6 kilometres, the Harley called for reserve, and your correspondent broke out in a cold sweat. I’d painstakingly filled that tiny tank at Yass to take every last drop, and 6.5 litres later (instead of the alleged 7.6 litres), I was relying on a claimed 0.9 litre reserve to get me the 10 kilometres. Was it really 0.9 litres? What if it was only 0.5 litres? I dropped the speed to 90 km/h, and we eventually made it to Tarcutta, no problem in fact (I later managed 17 kilometres on reserve on the way home), but I admit to some doubt about the wisdom of ever taking a Sportster outside the city again.

It might have been okay for Bronson – he was so cool he could have turned water into fuel if need be – but out in the real world, the Sportster seemed to have some limitations.

I’d learned my lesson, so another 70-odd kliks down the road, I topped up at Holbrook (“That’ll be $1.73 thanks … “), before stowing my helmet on top of my luggage and cruising out to Jingellic for an afternoon and evening of drinking beer, drinking rum, and lying about how fast I can ride a motorcycle.

The weather the next day was as wet and stormy as the cyclone raging in my head. The tiny tank turned out not to be the problem it was on the way down, with average speeds around the legal limit and the prospect of stopping every 130 kms for fuel and caffeine quite appealing. A less than full top-up at Jingellic had the bike on reserve 17 kilometres short of Tarcutta, but a soft throttle hand and some hard praying helped me through. The balance of the trip home was wet roads, wet toes, windy servos and lousy coffee – basically slow, uneventful and otherwise boring but for the uniqueness of the bike.

It would be easy to dismiss the 1100 Evolution Sportster as a totally impractical motorbike because of the tiny petrol tank. An absolute maximum touring range of 140 to 150 kilometres is limiting for even the occasional tourer, and that can be achieved only by chocking up the sidestand to get the bike vertical and patiently squeezing every last drop into the tank. Ride it hard, and you’d be lucky to get 120 kilometres.

Yet the tank is an important part of the Sportster mystique. It gives the bike a much smaller look and feel, allowing the engine to dominate the visual and sensual impact of a bike brimming with character.

From time to time, Harley Davidson has released variations on the theme with larger tanks (“Roadsters”) but these were never successful. The Sportster has been around for the best part of 30 years, and for most of that time, it’s been fitted with that same small “peanut” tank. Harley Davidson is probably closer to its customers than any other manufacturer in the world, a true believer in the maxim that the customer is always right. So who are we to argue?

The 8.5 litre tank was a bitch on this particular trip mostly because I required 600 kilometre days of it. Harley owners, virtually by definition, exhibit a more leisurely approach to their motorcycling, and a couple of weeks off work to cruise up into Queensland and back would be a pleasure on this bike.

The 1100 motor is infinitely more enjoyable than the 883, with bags of top gear grunt from 70 km/h through to 160 km/h. The 883, by comparison, gets a little breathless over the legal limit. The test bike had enjoyed some subtle exhaust modifications and carburettor tuning, giving it a smoothness that belied its 45 degree V-twin configuration, and also a little more of that traditional Harley sound — in all, a wonderful and relaxing touring engine.

Wind resistance was not a problem at close-to-legal touring speeds, and the rider’s seat is at least as good as the touring range, though some highway pegs would be a welcome accessory. The friction throttle was a nice touch. The front suspension, coupled with a 19-inch front wheel, provided a very comfortable ride, though the same could not be said for the rear shocks, which were woeful, bottoming out frequently and provoking some well-pronounced wallows. Despite the wallows, however, the bike was quite stable; not as good as some of the bigger Harleys, but the bike would hold a line once on it.

Apart from a drive chain requiring frequent adjustment, the Evolution Sportster is the closest thing around to a maintenance-free motorcycle and is light-years more reliable than its predecessor.

As for the standard of finish, it’s simply the best there is, and even in 1986, the Sportster remains an enormously cool motorbike to go tripping on.

I don’t know what happened to Bronson. I like to think of him out there on the highway, pulling his black beanie down over his ears to keep out the cold while he fills up at a rustic country gas station. He’s looking long and enigmatically into the eyes of this week’s heroine while he mutters something truly profound. She’s running her manicured fingers across the Seeing Eye mural painted just below the Sportster’s filler cap, sighing as she fills it with leaded. The tank holds just 8.5 litres.

One hundred and thirty eight kilometres up the road, he’ll switch to reserve and stop at another rustic country service station for more gas, another gorgeous and randy blonde, and yet another instalment of his destiny.

Fill ‘er up.

By Geoff Seddon. Two Wheels, May 1987.

1992 XLH 1200

The year is One Nine Five Seven. In the USA the privations of WWII are fading in the glare of a monster economic boom. US manufacturing industry – honed and tempered in the cauldron of war – is spewing out cars, TVs, dishwashers and hi-fis like there is no tomorrow.

Elvis is alive, thin, twitchin’ and scaring the bejesus out of a zillion parents. Teenage girls still shed tears over the quick, bloody exit of James Dean, while in Detroit, General Motors whips the covers off one of the few cages worth owning — the glorious ’57 Chevrolet.

Down the bottom of the planet, in Melbourne, Australia, Mrs Kennedy is also doing some baby-boom manufacturing, attempting to push out a son who she will call Stuart Edmund. Towards the end of a long, hard labour a nurse gives notice of impending relief by announcing, “God, it’s got a big white head.”

Meanwhile, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the Harley-Davidson Motor Company is going through some birth trauma of its own. The Pommies, whose arse the US has so recently saved with a bucketload of Lend Lease war toys and an invasion of Nazi Europe, have got their motorcycle factories back into civvies and are churning out a tidal wave of cute, light, fast sporting twins.

Worse still, US riders with a need for speed are giving the finger to heavy, expensive Harleys and signing up for ship-loads of British twins. H-D hits back with a pretty, unit construction, swingarm-framed flathead V-twin called the K, but the damn thing sits stillborn in the showrooms because it’s slower than a Schwinn treadly.

What to do? Give the poor little bugger some P-O-W-E-R. Off with the wimpy flathead and on with hot cams and 54 cubic inches of hairy-chested OHV. Harley-Davidson’s wild child is born: the 1957 883 cc XL Sportster. Yee ha! A ’50s superbike.

Thirty-four years and a million burnouts later, the Sporty is still around while the Norton, Triumph and BSA twins which inspired it are long and sadly gone. And in 1200 cc form the Sportster still brings a rebel yell when the fat plastic throttle is wound to the stop.

Enough history, let’s go for a ride. Push the key in just above the garish chrome horn and click on to discover that Bob Brown has legislated the lights permanently on. At least the ’92 models wear a quartz-halogen globe in the tiny cowled headlight, which lifts night time penetration from woeful to adequate. Pull the choke knob near the key and punch the big button on the right handlebar.

Chukoomph. Nothing. Sometimes the starter motor loses the battle with two 600 cc slugs and 9:1 compression but a second jab will always light it up. A new fast-idle circuit in the 40-mm Keihin carby makes warm up easy. Leave the choke on for the first few kays as the motor needs to be toasty hot to idle properly.

Grab the big clutch lever on the end of the buckhorn ‘bars and pull it in over a wide, firm arc. Levers, buttons and handles on Harleys are all a scale larger than other bikes. The clutch has been modified and is now smooth right through its take-up, even when hot and sweaty in traffic. Graunch into first gear, dial up a few revs and cast off.

The first, last and middling impressions on a 1200 Sporty come from the motor. The tiny tank, thin seat, slender frame and meagre running gear are there to give minimal life support services to the huge 45-degree V-twin with its distinctive parallel pushrod tubes positioning the bump sticks over four cams — one for each valve.

Let’s putt for a while, while the motor warms up. Power and vibes on the Sporty happen over three zones. The first zone runs from idle to just under 3000 rpm. Here the bike dishes up heaps of the low-rev torque all the Milwaukee Vtwins are famous for. Running around town with the tach under 3000 sees off all but the most determined cages and power delivery is quite smooth, although there’s thumping vibration through the seat on the over-run and belt snatch off idle. The motor pings like a sub’s sonar, even on high-octane fuel.

Now the bike’s warm and the choke is off. Let’s go for zone two. As the tach needle winds from three to five grand there are two nasty surprises. First off, all hell breaks loose in the vibration department. A pair of 600 cc jackhammers tied together on a common crank pin without the latter-day comfort of a balance shaft produce vibes fierce enough to destroy expensive dental work and loosen any un-Loctited bolt. Nothing puts out vibes like a Sporty; the rigid-mounted but balance-shafted 1340 cc Softail is smooth by comparison.

However, H-D has added some relief since Two Wheels last tested the 1200 Sportster in June ’88. A new transmission adds an extra cog to the old four-speed regime to give a rev-lowering overdrive; the chain final drive has been replaced by a low-maintenance, slightly smootherrunning Gates Kevlar belt and redesigned supports for the rear guard have hopefully fixed vibe-induced mudguard cracks.

The new transmission is claimed to be much stronger than the old four-speed, which had a habit of flogging out third gear. Shifting is positive but noisy and requires a firm flex from the left hoof to shuffle the cogs. There is a slight whine which settles down after around 15,000 km.

Nasty surprise two is the Boston Strangler has been at the induction tract. When revs reach around 4000 rpm from a whipped-open throttle the motor feels like it’s swallowed a watermelon. Some glassy-eyed bureaucrat has mandated a reed valve block on the air cleaner, which chokes the Sportster’s need for copious oxygen in the upper rev range. The result is hunting, hiccuping and no power.

Unfortunately for the environment the reed-valve block vibrated off during a stint of dirt riding on a private property and I had to spend hours running up and down the paddock looking for the errant lump of alloy. While whales died and the ozone layer dribbled away, I enjoyed a healthy engine, more power and better fuel economy …

The Sporty reaches its maximum torque of 86 Nm at 4400 rpm and shifting up at this point throws the bike down the road in loping, shaking bursts of motion. Here is the machine which terrorised the bitumen during the ’50s and ’60s. While it’s not within cooee of an FZR1000, it feels fast.

Grit the teeth, hold the loud handle against the stop and go for the twilight zone between 5000 and 6200 rpm. It’s like sitting atop a berserk threshing machine but necessary to transmit the last of the bike’s 47 kW, which arrives at 5200 rpm. Changing up is a big relief, especially on the test bike which had few kays on the odometer. Until the reed valve widget was stuffed into the inlet tract this year the Sporty put out a much healthier 51 kW at 6000 rpm and 97 Nm at 4000 rpm.

H-Ds take a good 10,000 km to run in and the motors loosen and smooth out considerably during this period. The test bike arrived with 782 kays on the clock and when it left my reluctant paws with more than 1500 kays it was operating significantly better.

The suburbs are petering out now and it is time for some country cruising which means a fuel stop is vital. The tiny peanut tank holds just 8.5 litres, giving a range of around 100 kays before the 0.95-litre reserve. Touring means keeping one eye clamped on the trip meter.

Shift into top on the freeway and marvel at gearing higher than the Indian Pacific. Top gear pulls 40 km/h per 1000 rpm, giving a theoretical top speed at redline of 250 km/h, although I doubt whether a well run-in example would produce much better than 210-220 km/h. At a semi-legal 120 km/h in top the Sporty is rotating at just 3000 rpm, which is unfortunately smack on a heavy vibe zone. It’s much smoother backing off to 100-110 or pushing on to 130-140. Fourth gear is close to the old ‘box and gives 30 km/h/1000 rpm.

The cop-infested freeway becomes tiresome, especially with the windblasting ride position, so let’s stop for juice and then find some corners. Line up a swoopy 45-km/h left-hander and grab a little front brake. Surprise, surprise. New pads and disc material mean you don’t have to carry a vice clamp around to extricate some retardation — there is now some bite in the single-piston, 292-mm front disc and lever effort is lower.

Pitch in at seven-tenths using the butt and wide buckhorn ‘bars for leverage, find the apex, haul open the throttle and feel the torque surge throw you onto the straight. This is serious fun. Let’s try a tighter one a bit quicker.

Peel into a 35-km/h right-hander at around eight to nine-tenths. This one’s got a few bumps in the middle. Now it suddenly becomes clear why a bunch of H-D buffs indulging in apres-ride bullshit all wave their arms like deranged orangutans. The long, soft, 39-mm front forks flex and the 19-inch front wheel skips sideways on the bumps while the skinny swingarm also has a flex just as the woefully underdamped rear shocks pogo skywards. Meanwhile, the exhaust header is bleeding chrome on the pavement, the right footpeg is graunching and the daggy 16-inch Dunlop 130/90 Elite is sliding.

The pair of arms white-knuckled onto the buckhorns are flapping for control just like a deranged orangutan…

It’s wise to give the Bankcard a bruising before pushing a Sporty hard. Lashing out on a set of Michelins, a fork brace, progressive-rate springs and heavier oil in the front coupled to a set of Konis at the rear will transform the bike. As it stands, the rear suspension is useless for anything except low-speed cruising while the rest of the rolling chassis is a notch better but could stand some research and development. Last decade Harley Evolutioned the motor; this decade the company might turn its attention to the rest.

Time to park for the day and cast a quick eye over what eleven-and-a-half grand has been spent on. Paint quality on the tank and metal mudguards is thick and lustrous, as is the chrome, and everything is held together by industrial strength nuts, bolts and fasteners. There’s an excellent, wide-tanged sidestand, thick, rugged control cables, good mirrors, a wonderfully loud horn, self-cancelling blinkers and new antivibration footpegs from the 1340 FXR series.

Maintenance duties on the hydraulic-valve, electronic-ignition equipped motor extend to checking primary chain adjustment, oil changes and carb tuning. Bone simple.

The test bike came adorned with $618.80 worth of gee gaws and knick knacks from Harley’s humongous, walletemptying accessories catalogue. Knick knacks included a set of $152.40 highway pegs (great for stretching the legs on the open road) and a $334 padded sissybar (great for keeping the sexual preference welded to the pillion seat). Gee gaws included an assortment of brass parrots, H-D nameplates and a chrome cover for the battery.

If you are after image the Sporty will impress the uninitiated but brings derision from Big Twin believers. To afficionados of the 1340-cc engine — bros and Rich Urban Bikers alike — the little Harley is the Skirtster or Mini-Glide.

So what? If a 1340 punter gives you a hard time then pin his beard back at the lights or waste him down a twisting road. At 213 kg the 1200 Sportster is 48 kg lighter than the most bare-bones 1340, has much better ground clearance and puts out almost as much power. Rather than being ‘the little Harley’ the big bore Sporty is an experience unto itself, more like a giant Triumph or Norton than a Big Twin Harley. It’s the most visceral motorcycle on the road and makes even the Moto Guzzi Le Mans seem like a smooth sophisticate. The Sporty rattles, shakes, graunches, runs out of petrol and provides face-splitting grins like no other two-wheeled device on the planet.

I became addicted enough to the experience after testing an 883 to swap a near-new Guzzi Le Mans for a slightly used 1200 Sporty and had my share of raucous riding until dire financial straits separated us. When the bank balance brightens we’ll get together again.

By Stuart Kennedy. Two Wheels, May 1992