1969 Kawasaki Mach III 500 and 1972 Mach IV 750

A Two Wheels road test may mean testing a 750cc sportster or a 50cc step through. It is difficult to be objective, for we love motorcycles and motorcycling and it is seldom nothing about a bike fails to appeal.

However, there comes into every man’s life, or in the life of every road tester, a machine. In my case, it was the Kawasaki Mach III. Instant Kamakazi! Just add throttle!

The whole machine is just too sudden. It feels light in the front end. It’s easier to do a wheelstand on the Mach III than any other cycle we have ridden. The revs and the torque build up gradually until 6000 (redline is 9000 rpm) and then everything happens at once.

The front end rears clear of the deck, the engine starts to scream and the III really gets into gear. And this is with a normal take-off too. If you really want a fright, rev the thing hard and drop it!

Fantastic on a drag strip. But on a normal road machine? The Mach III has been selling like mad overseas and it is possible it may do the same here. The price is right. However, I think that a Mach III buyer has a better than even chance of getting into trouble.

Basically the handling is good. The machine tracks well through corners, particularly on a trailing throttle. However, sudden applications of power cause it to alter line very suddenly and even small pebbles on the road will cause a similar loss of line.

Brakes are excellent and well up to performance. The headlamps, though, have done their dash on 50 mph cruising, which is just not good enough for a machine with the Kawasaki’s potential.

And potential it has. Straight line performance is fantastic – even on our test machine, which was badly in need of attention. Because of this we were unable to run any figures, but the sub-13 second standing quarter mile times seem quite feasible, especially given the 90 lb, bullet-shaped riders the Japanese factories use for testing .

It will top the ton in fourth gear with obviously a lot in hand. In fact, if it were not for the iffy roadholding, the Mach III would rate among the top two or three fastest point-to-point motorcycles. With a much braver/stupider rider than I, it probably still could.

It is hard to say just why the Kawasaki Mach III should behave the way it does. The basic design seems all right. The end result, though, is a powerplant far too powerful for the frame and suspension .

The front suspension seems to be lifted straight from the 250 cc Sidewinder, a street-scrambler, with adjusted rates and length of movement and altered rake. This may be the key to the problem, as the settings are not firm enough for high speed work. The front end seems to have a will of its own. It is possible while standing still to observe long movement range of the front forks. This softness does have one plus factor – the ride is very soft, no doubt to suit pampered American bottoms.

The rear suspension is also soft, and a little more tautness here would also help improve the handling.

The engine is superb. Even if it does not put out the 60 bhp claimed, the amount is more than adequate. It goes like no other 500 I’ve ever seen. Which is just what makes it such a potentially iffy motorcycle. It costs too little considering its performance – $950 is within the reach of most people and anyone desiring a little performance will think it obvious to spend only a little more and get the quickest.

This may sound as if the Kawasaki has no good points. This is not so. Its brakes are good, its engine is superb and the whole machine is very pretty to look at. I consider it possibly the best looking of the “new wave” cycles. Finish is hard to fault and it is very comfortable. All in all it has a lot of potential, but I’ll wait for the Mark II version before placing an order.

Rider and passenger comfort is very well looked after. The seat is long, with the upturned end racer style useful for positively locating a pillion passenger. The big grab handle at the back would please every rider who has ever had his ribs crushed by a nervous bird. The seat is also wide and soft. Coupled with the soft suspension, two up at the legal (in NSW) limit of 45 mph the Mach III is a very pleasant cycle indeed.

The gearbox is typical Kawasaki, positive and light to use. As the machine was so obviously designed almost purely for the US market, the designers put in a fair amount of thought on the positioning of pedals for occidental-sized feet. The result is a cycle where the foot controls are very well placed. It was never necessary to grope for the shift lever or the brake pedal. They are right where they should be. Mind you, a smaller person might find, because of the wide engine, the whole lot too far apart.

While the engine is quite highly stressed (120 bhp/litre compared with the BSA Rocket 3’s 80 bhp/litre), it is a willing starter, even from cold. Push in the little lever marked S on the right hand grip and a couple of prods on the starter were sufficient. When hot, one kick would do.

The engine idled evenly at all times and did not overheat, even in traffic. After the Daytona meet, rumours of the unreliability of the engine due to the middle cylinder seizing were running around. This may be true under racing conditions but I think it unlikely to happen under even the hardest road usage.

While the headlamp is not up to scratch, the horn emitted a healthy sound. The instruments were also legible at night, something that quite a number of cycles miss out on. They are very typical of the units all Japanese manufacturers are fitting these days and are good. Large dials, big white numbers on a black background and rock steady needles which tell the rider speed and revs accurately, not some vague reading which could be anything from 30 to 50 mph or 3000 to 4500 rpm.

The old folk song says something about “It takes a worried man to sing a worried song. but I won’t be worried long”.

I think that’s what worried me the whole time I rode the Kawasaki Mach III. Perhaps I’m being unjust, perhaps it is the greatest motorcycle of all time. But I think I’ll just wait for the Mark II version. Maybe they will have done something about the front end.

By Chris Wright. Two Wheels, November 1969

The American power race that hit the motorcycle market in recent years has only really been joined by the Japanese manufacturers in the last year.

Yet already we have reached the situation where it is hard to imagine much greater advances being made in the performance of the new breed of standard street bikes just becoming available on the Australian market, as a spin off from the US situation.

Specifically, Kawasaki seems to have come close to the ultimate in acceleration with their latest product.

The 500 cc Kawasaki Mach III roadster, fully equipped, is a mere 80 lb heavier than the Manx Norton, a pukka racer of the same capacity. What’s more, it is claimed to produce 10 bhp more than the Manx.

Acceleration on the Mach III is all that it is cracked up to be. On one occasion soon after I first rode the machine, I turned a slow corner on to a downhill straight less than a quarter of a mile long, and wound it up through the gears. As I was not trying 100 percent, I was amazed to find the speedo indicating 90 mph at the bottom of the straight.

The smoothness of the Kawasaki’s three cylinder, two stroke engine, is deceptive and gives the rider little indication of the bike’s speed. He is therefore liable to get into embarrassing, or even dangerous situations without realising it at first. Dealers will have a responsibility in selling the Mach III, to ensure that the buyer realises just what a potent weapon he is taking on.

Another misleading characteristic of the Mach III is created by its power band. At 3000 rpm the exhaust noise is really sporty in note, though not too loud. After all, the engine is firing as often as a four stroke single would be at 18,000 rpm!

Let out the clutch at 3000 and open the throttle, however, and the bike takes off at a disappointingly leisurely pace. Until the revs reach 6000, that is. Then, if you are sitting up, weight on the back and throttle more than half open, the front wheel does a little hop and the machine takes off at an alarming rate.

Drill for a fast takeoff is to keep the revs above six thou at all times. It would take great skill and nerve to use all the potential of this bike in getting “out of the hole”. The rider inexperienced in this sort of performance would be well advised not to be too exhuberant in starting techniques until he has become familiar with the bike.

The Mach III tested by Two Wheels is owned by Quinton Campbell of Ron Angel’s tuning service in Melbourne. The machine had done some 500 miles when Quinton lent it to us.

To date, he said, he had only taken it up fully in the gears once, and had seen 120 mph on the clock before quickly shutting off. The red band on the tachometer starts at 9000 rpm, but acceleration from 6000 is so great that, with five closely spaced gear ratios, it is not necessary to wind it up that far. Indeed, the power begins to tail off before the 9000 mark.

We found that in normal riding there is no tendency for the bike to break traction at the back wheel or lift the front appreciably. We persuaded Quinton Campbell to do a wheelie for the camera, which he confessed “gave me an insecure feeling”. Us too! But this sort of thing wouldn’t happen if you weren’t trying. Quinton reported that the bike is only really hairy in the wet, and that would be expected.

Cornering at normal, even fast, road speeds is fine, and the Mach III has a very light feel so it can be flicked about in city streets with ease. But at extreme angles of lean, and when the throttle is used hard out of a bend, the bike tends to wallow.

The owner of the test bike gave a lurid demonstration of this using all the road in a display of real cornering. But as he is the Hartwell Club 250 cc road race champion, his cornering is a good deal harder than most. Part of this problem seems to be caused by an insufficiently rigid rear swing arm, but possibly stiffer suspension would go a long way toward curing it for road racing use, which is the intention for this particular bike.

To put this question of the Kawasaki’s handling into true perspective, it would be well to quote the following incident which happened on the way to our test area. Leading the way in a Datsun 1600 on a road he knows very well, its expert driver had the front tyres shrieking and growling in protest round a series of long, fast bends: the Kawasaki was right behind the whole time with no difficulty whatsoever, and its owner sitting up grinning.

With a bike like this Kawasaki all questions not related to performance are just about irrelevant: with this exhilaration you don’t need anything else. Especially for under $1000.

However, for the record…

Flexibility is something of a paradox. On the one hand, it is quite possible to drive the Mach III at 20 mph in fifth gear, with no complaints from the engine or transmission. At the same time, acceleration from these revs is practically non-existent. Drop four cogs and it’s a different story. Neutral is below first, which is convenient for town work but won’t suit racing riders.

There would be a few criticisms if the Mach III was mistakenly used solely as a tourer. Apart from the lack of low to mid range power, suspension is very soft and comfortable in feel, but with the bike’s light weight, causes strong reactions to tramlines and such. Fuel consumption would probably cause a few problems, too, despite the four gallon tank. Although the engine is only slightly wider than the rotary valve Samurai, the rider’s legs are kept far enough apart to prove uncomfortable on a long trip.

The double note horn sounds good but is not loud enough. An exceptionally firm handrail runs directly into the rear frame. Unfortunately when you hit 6000 rpm it won’t help the passenger, who just has to cling on to the rider.

Togetherness is a hot Kawasaki.

Brakes on the test model were not entirely up to scratch, being too spongy in feel, and the rear one just wasn’t powerful enough. However, they could well improve greatly when adjusted after initial bedding down.

One difference between the Mach Ills sold in Australia and their US brethren is that ours don’t have the revolutionary electronic ignition system with pointless plugs, but the more conventional three coils and normal type plugs. Australian TV sets, we are told, don’t take kindly to this latest Japanese wizardry. Whatever the reason, there were no complaints with the electrical system on the test bike, and starting was very easy, hot or cold.

When I went out to ride the Mach III for the first time, Ron Angel said “When he stops shaking he can start writing”. Well, now I’ve stopped writing I’ll be willing to start shaking again on this Kawasaki – really a super sports motorcycle.

By Peter Chambers. Two Wheels, November 1969

Running the standing quarter in under 15 seconds isn’t hanging around. With at least 60 bhp on tap and some practice, 13 seconds is possible on most big machines. But hitting twelve and a half seconds with nearly half of that on the back wheel is mind-bending.

That this performance should be available from an over-the-counter bike that is the cheapest in its class will no doubt make the Kawasaki Mach IV a best seller.

Within 24 hours of the new model Kawasaki’s arrival, our test model had been registered and A grade production racer Bill Crawford was running it in on interstate runs. He wanted it for the Victorian TT races at Phillip Island in January. Although good times were recorded in practice for the event, Bill had the misfortune to drop it on a left hander and that took the edge off his racing for the day.

A short time later his sponsor, Melbourne’s Peter Stevens, had put right the damage and handed the bike to our tester for a fortnight’s fast riding, as well as providing a new machine to use for our cover shot.

Apart from the lack of flashers the test bike was absolutely standard and had covered nearly 2000 miles. Despite its slight brush with the tarmac and many hard laps around the Island circuit the bike was flying and in perfect condition for the type of performance we enjoy wringing out of a superbike.

When the bike was picked up the similarity of the three models that were lined up in the window showed Kawasaki’s thinking clearly – “When you’re on a good thing stick to it”.

The 350/3, 500/3 and 750/3 have the same layout and near-identical styling. At a glance they all look the same except for marginal differences in external engine sizes and a drum brake on the 350.

The previous model triples have been the fastest in their class but since the 500 Mach III was first introduced many refinements have been added to the basically good sports layout.

All these improvements are highlighted in the Mach IV which boasts a torsionally rigid frame, front disc brake and a flat power band. Perhaps these three points were the main complaints levelled at the sports performance of the fast 500 which suffered from unnerving twitches on bumpy bends under power, brakes that faded away after a few hard stops and a power band that required nothing short of a pilot’s co-ordination in linking revs with gear ratios.

For a reason we cannot figure out the gear change has been altered from the normal one down, four up, to neutral at the bottom and then all up. Although this system is good for the positive selection of neutral, its main drawback is when going down through the gears for a tight bend. A conscious effort is required to avoid over-running the shifts and ending up in neutral with a screaming engine.

The gearbox works as a gearbox should, short, positive and silent shifts with false neutrals being the description given to other makes. Both the box and clutch behaved excellently under test conditions where over 70 bhp was tearing through them in relentless acceleration runs.

Lift-off is the best way to describe what happens when the clutch is released at anything above 3000 rpm. Other sports performers demand a great deal of concentration to keep the front wheel in the air, but with the Mach IV, the concentration is needed to keep the front wheel on the ground!

The same thing happens in any of the first three gears once the bike is moving. The rider needs to open the throttle with the intention of using only a fraction of the power to blast away from traffic. We were amazed at the way the bike could lift the front wheel with ridiculous ease and hold the wheelie until the rider wanted the front end down for steering. That’s the result of 74 bhp working through a 420 pound machine, but it’s hardly a desirable characteristic.

Fortunately, the bike doesn’t have to be ridden at peak revs. Unlike its smaller brothers, the 750 can be ridden in top gear at 30 mph with ease, and is the most tractable sports Kawasaki triple.

This is because its tune is milder than the smaller-capacity machines – only 98 bhp per litre as against 120 bhp per litre for the 500 and 130 bhp per litre for the 350. This is a result of the drop of volumetric efficiency that occurs with tuned engines as the capacity increases for the same number of cylinders, despite near-identical design.

To prove the bike can be “walked” along keeping the tacho needle under three grand, we crept the machine around at the same revs as the road-speed and recorded nearly 50 mpg on the open road in top gear and 36 mpg around town. But this was not fun and we soon gave it away.

As spectacular as its acceleration is the Kawasaki’s top end. A good way to judge a superbike is the way it will pull away from the ton. Most 750s arrive at the three figure mark with one gear to go, and selecting top means a bit of a boost to 110 mph with speeds to over 115 coming with luck and having the length of road to wait around on.

The Mach IV will willingly rev to 110 in fourth and hitting top is the same as selecting 120 upon request. Due to the wind resistance of the high handle bars speeds in excess of 120 require the “bite the filler cap” position and even then only another five mph is gradually added.

As unequalled as the “off the line” acceleration is, belting through a turn at 90 in fourth, opening the throttle and just hanging on as the bike catapults down the straight in a way that NO other machine can live with it, is equally exhilarating.

But you pay for the unreal power, and heavy-handed owners could justify investing in their own filling stations.

Under normal conditions, giving the power an occasional zip to keep the reactions in trim but mainly just staying ahead of normal traffic returns 30 mpg in town and nearly 40 mpg in the country. But should the rider take a liking to lifting off at every opportunity and scorching along in the open country till his wrists ache with hanging on he can expect 11 mpg (we averaged that on the acceleration tests) and 18 mpg at speeds around the ton.

Throughout the test the machine handled perfectly at all speeds with no hint of wincing under full power no matter how bad the bends, with the damper screwed down or not. Ground clearance is excellent and we touched the swivelling footpegs under maximum lean only a few times.

The lack of power from the back brake was more than compensated for by the gigantic 12 inch front disc. Grab is completely lacking and our 30 mph to a standstill test in 25 feet is a bit misleading since the first 10 feet of application lacked the instantaneous snatch of self-applying leading shoes, but the last 15 feet sees the pads really gripping and the front tyre tearing lumps from the road. Naturally enough, fade is a word not used when talking about an efficient disc brake.

Other features we were impressed by included the vacuum fuel tap, full-length rear mudguard, the lack of plastic on such a low-priced machine (the side-panels and chain guards are steel; only the headlight nacelle is plastic), the convenience of the rear seat bump compartment (although a seat lock would be good), the transparent oil tank level sight tube, and the oil reservoir on the left hand side which holds a separate oil supply for the rear chain.

The pitiful little horn would be more at home on a step-through 50 .

A rider of any proportions can quickly set the controls to his liking on the Mach IV. Not only are the hand levers and bars adjustable but the foot pedals as well. They are set on splines to vary their angle and with screw verniers to adjust their height.

No doubt this latest sports offering from the Kawasaki stable will be as controversial as their other machines which hold the distinction of being the fastest in their class. People will criticise the Mach IV for unreasonable fuel consumption, but they can do so only with a slower bike for comparison.

Whatever will be said about the Mach IV cannot take away the fact that it leads the superbike class with its dynamic and exhilarating acceleration, and that it’s available out of the crate at a price much lower than any other 750.

By Derek Pickard. Two Wheels, May 1972.

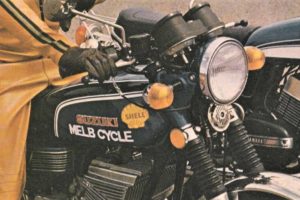

Guido from AllMoto takes a detailed look at the mighty Kawasaki two stroke triples, including a 750, pictured below, currently being offered up for auction by Shannons, here.